The garden of my house in Perth, Scotland, lost its iron rail fence in World War II – not to an enemy bomb, but to patriotism. All over the United Kingdom, iron railings got chopped down in parks and gardens to support the war effort. Here's a link to a newsreel from 1940 showing men collecting railings in a London park!

https://www.britishpathe.com/video/park-railings-for-munitions

The idea was that the iron would be melted down and used to make ammunition and armour for tanks and ships, although nobody’s really sure if that happened – there’s a rumour that London’s iron railings were all dumped in the Thames, and I’ve been told that Perth’s ended up in landfill on St. Magdalene’s Hill.

Parliament’s Hansard report for 13

July 1943 tells us that somebody wanted to know what was being done with all

that collected iron. Lord Hemingford commented, “It

has been felt that an injustice has been done to a very large number of usually

uncomplaining and patriotic people. This question of the requisitioning of

railings and gates is rather like eczema; it is not very serious, but it is

most confoundedly irritating, and causes a vast amount of bad temper.”

(source: https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1943/jul/13/requisitioned-railings)

For years, whenever I looked at the stumps of those railings in my garden wall, I thought of them as my house’s wartime scars. What I didn’t realize was that World War II took away something far more tragic from my house than its decorative iron railings. It took away the boy who’d come of age in that house and who’d still lived there when he went to war as a young man, the only child of the couple who lived in that house for forty years. He left my house to go to war and he never came back.

He was a navigator in the Royal Air

Force. He was part of a team of “pathfinders,” a dangerous job in which an

advance aircraft would have to find and mark an attack site for a bomber

squadron, dropping flares in the dark that would light up the enemy target. On 7 Dec. 1940, he and five other crew members

took off from RAF Stradishall in Suffolk in their “Wimpey” – a twin-engined

Vickers Wellington bomber. They flew through atrocious weather in the dark to

Germany, along with two other pathfinder aircraft, to mark the target for a

bombing raid in Dusseldorf. They vanished later that night somewhere over the

North Sea – “Aircraft failed to return,” is what the official reports said.

A Wellington

crew

(source: https://www.lancs.live/news/lancashire-news/lancaster-bomber-brave-daredevils-who-24064051)

Let me tell you about Chick. (His real

name was Charles.) He was a mild-looking young man with dimple in his chin –

his RAF portrait is in black and white, but I think he must have been like

Kate, his mother, short and lightly built, with brown hair, those amused eyes

blue. Robert, Chick’s adoptive father, ran a fishmonger’s shop in Perth, where

Chick helped out, but in 1939, with war looming, he joined the Royal Air Force

as a reservist.

Late in August 1939, just before Germany

invaded Poland, one of Chick’s mates who was also a reservist got his

calling-up papers. The friend and a few others turned up at Chick’s house – MY

house! – at eleven o’clock that night, and they all decided they’d have one

last night on the town before they were called into action. Chick drove them from

Perth to Dundee where, arriving after midnight, they had a couple of drinks and

checked out a couple of all-night coffee stands before heading back to Perth at

about three o’clock in the morning.

That’s when Chick ignored a stop sign,

was spotted by a waiting policeman, and got pulled over for driving under the

influence of alcohol – which apparently he didn’t have a very good head for!

He was fined £10 and given a six month

driving ban. He was contrite and honest about what had happened, and solicitor

who defended him pointed out that it was Chick’s “first time in trouble”! (Source:

Dundee Evening Telegraph, 25 Aug. 1939, page 6).

See my source note there – I got this

story from an old newspaper. It’s available online in the British Newspaper

Archive. Actually, everything I know about Chick – the details of the colour of

his mother’s hair and eyes, the kind of plane he flew, the date of his disappearance,

even his nickname – I dug up by accident simply because I just wanted to know

more about my own old house.

And in the wider sense, isn’t that the

real reason we dig up history – because we want to know more about our own

house, our own city, our own people, our own world? To learn from them, to

connect to them in their strengths and to correct their weaknesses?

I tell this as a coherent story, as if

I knew these people, Chick and his family and friends. But what I know about

them I found through scraps, fragments, puzzle pieces that I’ve fit together:

RAF war graves memorials, stories and police reports and personal columns in

local newspapers, internet queries on ancestry chat boards, wartime bulletins,

photographs, voting records, passenger lists for ships and airplanes.

Look at that – the scrap metal from

his own fence railings may have become part of the Wellington bomber that Chick

died in.

All my stories begin this way –

finding connections between the ordinary and the extraordinary, between daily

life and drama, between the past and the present. I hope this gives you some inspiration

for finding your own fascinating connections!

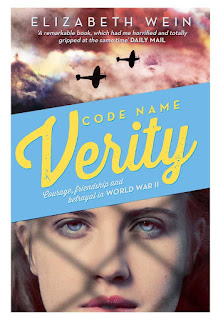

Elizabeth Wein is a recreational pilot and the owner of about a thousand maps; flight inspires her young adult novels and non-fiction. Her best-known book, Code Name Verity, was short-listed for the Carnegie award and became a number one New York Times bestseller in 2020. She has published three short novels with Barrington Stoke, including Firebird, which won the Historical Association's Young Quills Award for Historical Fiction in 2019. Look for her latest flight-inspired historical thriller, Stateless, published by Bloomsbury in March 2023.

Amazing story, wonderful pictures! Thanks for digging!

ReplyDeleteThank you! We're so glad you enjoyed it!

Delete