I was always

one of the spooky kids – my bedtime reading was filled with ghost stories and my

teenage fashion choices leaned towards goth. My mum took me exploring in

graveyards and my uncles gave me books on poltergeists and real life ghost hunters.

Maybe it was inevitable that I’d write a book with death front and centre.

Valentine

Crow and Mr Death is about a foundling boy who, due to a clerical error, is

apprenticed to the Grim Reaper. The challenge was finding a narrative about

death that was the right sort of spooky for middle grade readers.

It was

daunting. I was writing during a pandemic, watching my own children learn about

death in a scary and sudden way. I didn’t want to sugar coat things – kids can

see right through that – but I also didn’t want to terrify anyone.

We’re not

very good at talking about Death in our culture – we distance ourselves from

it, and it’s taboo to talk about in many circles. But for as long as we’ve been

telling stories, we’ve been telling stories about death. We need stories to get

our heads round the stark truth: one day, we won’t be here any more. As simple

and as incomprehensible as that.

I read a lot of traditional folk tales in my research and found that stories about death tend to have two key messages – firstly that death is inevitable and necessary, and secondly that everyone is equal in death.

One of my

favourites – which I borrowed to create a character in Valentine Crow – is

‘Mother Misery’. An old woman tricks Death into climbing an enchanted fruit

tree which traps him in its branches. Initially her neighbours are pleased but

over time they begin to suffer, as the very sick and old can no longer pass on

to the afterlife. She lets him down only once he promises never to come for

her, which is why we will always have misery in the world.

Another story tells of a young man who imprisons death to save his mother. But when he tries to cook their supper, he can neither pick vegetables nor kill a chicken, as animals and plants can no longer die. There’s a strange sort of comfort in these tales, because however dark they get (and some of them get VERY dark) they offer us a ‘why’ for death.

Turning death

into a character scales it down to something easier to understand – once it has

a face and a voice, it’s something we can interact with, bargain with, rail

against.

The earliest depiction of death as a cloaked skeleton carrying a scythe was in the 14th century, as the black death swept through Europe and cut down victims swiftly and indiscriminately, as a farmer cuts down a field of wheat at harvest time. The name ‘The Grim Reaper’ came much later, in 1847, and both name and image have stuck with us as the instantly recognisable figure of death.

At around

the same time a motif called the ‘danse macabre’ became popular in medieval art.

Grinning skeletons dance hand in hand with living people – kings, bishops and

beggars alike - leading them merrily towards their demise. It works as a

comfort to the poor and a warning to rich: whatever your status in life, we’re

all going to the same place in the end.

These are often surprisingly playful and comical images, and I love them for that. They’re not (only) an expression of the terror of death, but also evidence of dark humour in the face of unpleasant reality. The urge to take something ugly and scary and turn it into art and laughter.

It’s still

with us, in our zombie movies and haunted house rides and on Halloween, when we

dress our precious children up as ghosts and skeletons and ply them with sugary

treats. An acknowledgment of death, and a defiance of it: we see you there,

reaper, but we’re going to celebrate anyway.

Writing

challenge – The Grim Reaper is a personification of death. Create a

personification of a different abstract idea or concept (hope, truth, power

etc). Think about how they might look, speak and move and how they might

interact with other characters.

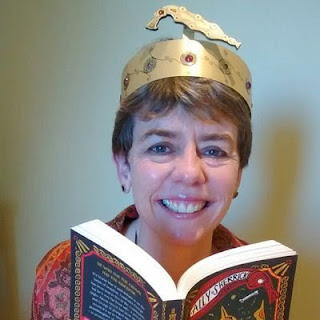

Jenni Spangler is the author of The Incredible Talking Machine, The Vanishing Trick and Valentine Crow and Mr Death.

Theatre school drop out, ex-999 operator and occasional forklift driver, Jenni writes children’s books with a magical twist. She loves to take real and familiar places and events and add a layer of mystery and hocus-pocus.

She was part of the first year of the ‘WriteMentor’ scheme, mentored by Lindsay Galvin, author of ‘The Secret Deep’. As well as her magical middle grade novels, Jenni writes short contemporary YA stories for reluctant and struggling readers, including Torn and Wanted for Badger Learning. Jenni has an Open University degree in English Language and Literature, a 500 metre swimming badge and a great recipe for chocolate brownies. She lives in Staffordshire with her husband and two children. She loves old photographs, picture books and tea, but is wary of manhole covers following an unfortunate incident.

You can find out more about Jenni and her books at www.jennispangler.com and follow her on twitter and instagram