In conjuring up the historical setting for Dido’s adventures, my other literary inspiration, besides National Velvet, is Rosemary Sutcliff’s The Eagle of the Ninth, the tale of a young Roman soldier’s quest to discover what happened to his missing father’s lost legion. As well as being a riveting adventure story, I’m in awe of the way Sutcliff brings the bleak landscape of Roman Britain to life but in a way that never feels like she’s borrowing on cliched tropes about the ancient world.

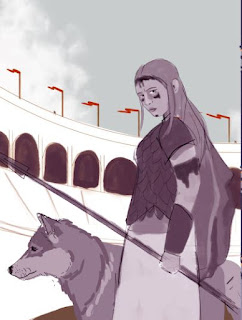

That was my aspiration with the Circus Maximus series. Plenty of research underpins the novels, but I hope the reader never feels that they’re having a history lesson. Instead, by immersing them in the period, I want them to feel as if they are right there besides Dido and her fellow characters, smelling the same scents in the air, feeling the noise coming up through the ground as the vast Circus crowd roars and stamps its feet in anticipation. The ultimate goal is to make people think I know what it’s like to drive a chariot, even though – a little to my regret – I never have.

To that end, much of my background research prior to writing the series was into the world of chariot racing, ancient Rome’s favourite sport. I drew from a tapestry of different sources – literary, artistic and archaeological. Written eyewitness accounts from the time provide a glimpse into the build-up to a race – the charioteers drawing lots to see which of the Circus’s twelve starting gates they will be allocated; stable-hands and grooms holding harness, plaiting manes and trying to soothe their four-legged charges; the horses’ hot breath puffing through the gates. Thanks to inscriptions in honour of winning teams, we know the names of hundreds of horses who raced at the Circus and even their colour and sometimes their breeding.

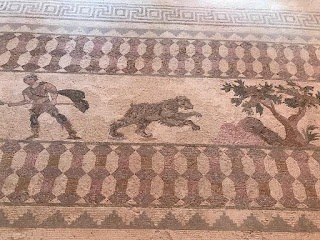

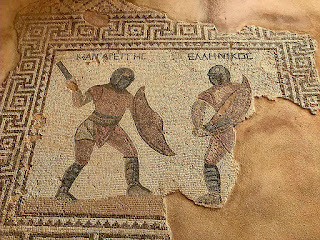

No actual Roman racing chariots survive from the ancient world, but little model replicas – such as this one currently held by the British Museum - assist with their reconstruction and demonstrate how much smaller, flimsier and more dangerous to drive they would have been than the cumbersome vehicles seen in the classic film Ben-Hur. Meanwhile, mosaics from North Africa, where many of the best horses and drivers began their careers, give us close-ups of the uniform of the charioteers, their coloured tunics denoting which of the four big racing factions they represented – Reds, Blues, Whites and Greens.

Of all the evidence I drew on in writing the books though, my favourite are the games tokens that were found in the grave of a young Roman girl from the fourth century. Six little ivory discs, with an image of a horse on one side and a victorious charioteer on the other, they were buried with the girl alongside a doll with jointed arms and legs and plaited hair. One theory is that the tokens were keepsakes from a day at the races, and it’s a poignant image, that idea that maybe this girl loved going to the Circus and her family buried it with her as mementoes of a happy day. From my point of view, it’s always seemed unlikely that amongst the quarter of a million people who could fit into the Circus Maximus on race day, there weren’t at least a handful of girls – young Velvet Browns of the past – who longed to be down on that great track themselves, competing for glory, hearing their name on the crowd’s lips. That’s an image I always hold in my head as I write Dido’s story.

You can watch Annelise Gray's video on Roman Chariot Races by clicking here.

Annelise Gray was born in Bermuda and moved to the UK as a child. She grew up riding horses and dreaming of becoming a writer. After studying Classics under Professor Mary Beard, she earned her PhD in 2004 and has worked as a historical researcher and as a Latin teacher. Her debut children’s novel, Circus Maximus: Race to the Death (Zephyr Books) was longlisted for the 2022 Branford Boase Award and named as a Children’s Book of the Week in the Sunday Times. There are now two more titles in the Circus Maximus series, Rivals on the Track and Rider of the Storm, which was published on World Book Day this year.

Author website: www.annelisegray.co.uk

Twitter: @AnneliseGray

Annelise Gray's books are available online and from bookshops, including The Rocketship Bookshop, Salisbury