Since my first published children’s book, Black Powder, I have always included an heroic – and sometimes downright mischievous – animal sidekick in my stories. In Black Powder, about two children caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, my hero Tom has a white pet mouse called Jago. Since then I’ve included a dog, a raven, a monkey and a wolf in other stories. And I’ve created two new animal heroes in my current historical work in progress, though I’m not quite ready to reveal their identities yet!

My own earliest memorable brush with an historic beast was a visit to the Natural History Museum in London and a meeting with Dippy the Diplodocus, who in the past few years has been making a grand tour of the UK and thrilling visitors young and old wherever he – or she? – lands. Dippy, as I later discovered, is a composite of many rather than one individual dinosaur’s bones, and also a cast taken from the ‘original’ Dippy housed in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, USA. But whatever its origins, it still has the power to excite young imaginations, as it did for me.

Other actual remains of creatures from the past which have intrigued and wowed me in equal measure over the years include the mummified cats on display in the Egyptian galleries at the British Museum, a plaster-cast taken from the remains of a dog caught in the ash flow of the devastating eruption of Vesuvius at Pompeii complete with its collar, and the skeletons of eleven horses buried with their presumed royal owner in a Viking-age ship burial at Ladby in Denmark in the early tenth century.

In addition to the remains of real live – or perhaps we should say ‘real dead’ – creatures that have come down to us from the past, the evidence of people’s passion for, and fear of animals throughout time is all around us, and across all cultures too.

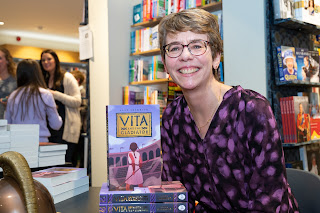

For example, I love this mosaic of beasts fighting in the gladiatorial arena from a Roman villa in Cyprus. In fact, I used such scenes as part of my research into my Roman-set story Vita and the Gladiator in which my heroes, Vita and Brea are pitted against their own fierce animal combatants.

Medieval gargoyles on the outside of church towers and walls are also a favourite. I always look up before going inside to see if I can spot these strange, often nightmarish creatures created by medieval stonemasons, including this one of a devil or imp on St Peter’s Church in the Cotswolds town of Winchcombe. The word ‘gargoyle’ comes from the Old French word gargouille, meaning ‘throat’ and describes their practical function as waterspouts diverting rainwater from the roof. But historians believed they may also have served as charms to keep evil spirits away, or as a method of warning parishioners against committing sins.

And of course real and fantastical animals are often included in tapestries, on coats of arms and in sculptures and paintings too. For example I was lucky enough a little while ago to see the exquisite Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

This series of wall-hangings was woven in around 1500, probably in the South Netherlands, and is believed to have been a wedding gift destined to be hung in the happy couple’s bedchamber. The tapestries tell the story of the taming of the mythical unicorn – whose horn was believed to have magical properties to detect poison and purify water. But they also depict many recognisable real-life birds and animals including pheasants, ducks, rabbits and lions.

And on another holiday, this time to the city of Bangkok in Thailand, I visited the beautiful Buddhist temple of Wat Arun, home to many amazing sculptures including this one of the deity Indra on his three-headed elephant.

Meanwhile, the image of a monkey in a painting of Katherine of Aragon, the first wife of the Tudor King Henry VIII, helped inspire the creation of Pepin the monkey in my own story The Queen’s Fool. I knew that monkeys in those times were kept as pets by the nobility in grand houses in England and Europe. But they would have seemed strange to ordinary folk, especially my hero, Cat Sparrow, who has grown up in the enclosed world of a nunnery. When she first encounters him, she mistakes Pepin – or Pippo as she prefers to call him – for some kind of giant spider. Understandable if you’ve never seen a monkey before!

Animals also make a frequent appearance on items of jewellery, clothing and even armour throughout history. While studying medieval history at university I learned about the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk. I was fascinated to discover that many of the treasures buried with King Raedwald whose monument it’s believed to be, depicted creatures both real and imaginary. I’ve talked in another TimeTunnellers post about the Anglo-Saxons’ passion for dragons, the most striking examples of which are on the warrior’s helmet included in the burial. But there were also stunning depictions of wolves and eagles – two of the so-called ‘beasts of battle’ – on other items including the king’s purse and shield mounts.

And from a completely different culture - South America this time - this beautiful gold frog pendant. It was made somewhere between the 8th and 16th centuries and may have been a totem, a sacred object representative of a spirit being with supernatural powers.

But perhaps my favourite representations of animals and birds in the past are in the illuminated manuscripts produced by monks in the scriptoria, or writing rooms, of medieval monasteries. The illustrations included in the copies of holy texts they made – including the beautiful early 15th century Sherborne Missal now in the British Library – were often both a celebration of the natural world and a very human testament to their vivid imaginations and colourful sense of humour. A form of escape perhaps from the bleak conditions they were working in sat at their desks in those cold and draughty monastery buildings.

Best of all, are the illuminated texts known as bestiaries. A bestiary was a compendium of beasts, with illustrations of animals and an accompanying description of their natural history and which usually included a moral message for the reader – mainly monks and clerics – drawn from the beast’s assigned religious meaning. They were first produced by ancient Greek scholars, but versions of them became increasingly popular during the Middle Ages, especially in England and France.

Bestiaries included both beasts that existed – for example pelicans, lions, bears and wild boars – and ones – spoiler alert! – such as griffins, unicorns, dragons and basilisks that didn’t. But no distinction about whether they were real or imagined was made in the entry.

There’s some debate among academics today about whether medieval people really believed the more fantastical ones actually existed or else accepted that they had been created for teaching purposes. But either way, many of these amazing beasts have found their way into fantasy stories and films of more modern times including works like Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and J.K. Rowlings’ Harry Potter series and its spin-offs to name but a few.

Writing Challenge

Pick your own favourite real-life animal and taking inspiration from imaginary creatures in the past, with a wave of your pen transform it into a fantastical creature to include in your own 21st century bestiary. What sort of additional physical features will you give it to make it suitably weird and wonderful? Where does it live? What does it eat and drink? What sort of noise does it make when it’s happy, or angry? What special powers might it have? Write a few paragraphs describing it. And don’t forget to include a drawing of it too!

Ally Sherrick is the award-winning author of stories full of history, mystery and adventure.

BLACK POWDER, her debut novel about a boy caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, won the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award. Other titles include THE BURIED CROWN, a wartime tale with a whiff of Anglo-Saxon myth and magic and THE QUEEN’S FOOL, a story of treachery and treason set at the court of King Henry VIII. Ally’s latest book with Chicken House Books, is VITA AND THE GLADIATOR, the story of a young girl’s fight for justice in the high-stakes world of London’s gladiatorial arena.For more information about Ally and her books visit www.allysherrick.com You can also follow her on Twitter @ally_sherrick