People all over the world celebrate Christmas in different ways. From the enormous Yule Goat constructed of straw in Sweden, to the Pastorelas (Shepherd’s Plays) of Mexico, to a game of Trivial Pursuit alongside a box of Quality Streets in the UK, people have created their own traditions around this major Christian festival.

But what about people in the past? How different were their Christmas celebrations from our own? To find out a little bit about what might have changed, let’s go back five hundred years to Tudor England under the reign of King Henry VIII …

The Twelve Days of Christmas

In Tudor times Christmas really was twelve days long! Starting on December 25th and ending on January 5th, people downed tools and took part in a number of traditions, one for each of the twelve days.

On Christmas Eve (December 24th) people would decorate their spinning wheels with greenery brought in from outside, signifying that work was stopping for the duration of Christmas. Christmas trees came a lot later - in Tudor times people would ‘deck the halls with boughs of holly’, and festoon their houses with ‘the holly and the ivy’.

On Christmas Day itself people would eat! The Tudors knew how to throw a party, and they would have feasted in the best style they could afford.

Roast meats featured prominently (including Turkeys, which were a new delicacy and could be seen being driven in huge flocks from London to Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire) as well as pies that contained two or three different kinds of bird meat alongside fruit and spices.

Mince pies were originally filled with actual minced meat, spiced and mixed with fruit - until later the meat was taken out, and all that remained was the spiced fruit with the rather confusing name of ‘mincemeat’!

One famous tradition is that of the Boar’s Head, commemorated in the Boar’s Head Carol. In a spectacle echoing back to ancient pagan origins, a boar’s head would be cooked and garlanded with fruits and herbs, and brought into the feasting hall on a magnificent platter. The Boar’s Head Feast is still celebrated in Oxford University’s Queen’s College to this day!

The Feast of St. Stephen was on what we now call Boxing Day. It was a day for charity and giving to the poor, and it’s immortalised in the carol ‘Good King Wenceslas’ who looked out on the Feast of Stephen to see a poor man struggling through the snow, and was moved to bring him ‘flesh and wine’.

Child Bishops were appointed in churches from 6th December until Childermas on 28th December. A young boy, usually a member of the choir, would be adorned with all the regalia of a bishop for this time, and would take services and preach sermons!

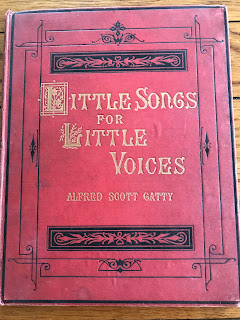

O sisters too, how may we do For to preserve this day This poor youngling for whom we sing, “Bye bye, lully, lullay?”

New Year’s Day was the traditional day for giving gifts. People gave gifts to show their appreciation to those in authority over them, and those at court were expected to give presents to the king.

Tudor Christmas presents could be expensive - but they were an excellent way to make sure you stayed in favour in the coming year! Just think about that next time you’re doing your Christmas shopping …

Father Christmas

One of the most endearing and bizarre Tudor Christmas traditions was the appointment of a Lord of Misrule to preside over the twelve days of festivities.

Revived by Henry VII, the post of Lord of Misrule was a way to upset the normal order of things. Someone would be chosen to direct all the Christmas celebrations, and would preside over them in a mock court, receiving mock homage from the revellers.

In Scotland, the same position was held by the Abbot of Unreason - although with the progression of the Reformation across Britain these traditions slowly faded away.

The idea of a Lord of Misrule does persist today, however, in the unlikely form of Father Christmas! Lords of Misrule were sometimes given names like ‘Captain Christmas’, ‘The Christmas Lord’ or ‘Prince Christmas’.

In 1616, the playwright Ben Johnson put on a Christmas play featuring an old man called ‘Christmas’ or ‘Old Gregorie Christmas’. He had sons and daughters called ‘Mince Pie’, ‘Misrule’, ‘Carol’ and others, and he had a long beard.

So the idea continued through the 1600s, the character appearing in numerous Christmas plays. He always personified Christmas parties and games, however, and had less to do with the idea of bringing presents. And as you can see in the picture above, he sometimes rode a goat!

Another tradition had been around in Europe for a long time - that of St. Nicholas, based on the real-life figure of a Bishop from Turkey. On St. Nicholas’ day (6th December) children were given presents to commemorate his gold-giving exploits.

According to tradition, St. Nicholas (or ‘Sinterklaas’) would deliver presents by passing through locked doors or descending chimneys. In Dutch markets, Sinterklaas impersonators could be found wearing his distinctive red and white robes

It’s possible that the legend of Sinterklaas crossed the Atlantic to the North American Dutch colony of New Amsterdam, which later became New York.

However it happened, Santa Claus born, and eventually immortalised in Clement Clark Moore’s poem, ‘The Night Before Christmas’, where we find many of the features of our familiar Santa, including a huge belly, red costume and reindeer.

For a while Santa Claus and Father Christmas existed side-by-side, even appearing together in an 1864 story by Susanna Warner. But eventually the two merged, although in the UK the character has traditionally kept the name Father Christmas, harking back to the Lord of Misrule and providing us with a fascinating link to the Tudors!

And Christmas traditions are still evolving, with Elf on the Shelf and other festive celebrations taking their place in the hearts and lives of British people.

Writing challenge

About the author

Sources

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/A-Tudor-Christmas/

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/members-area/kids/kids-tudors/twelve-days-of-christmas/

https://kriii.com/news/2022/medieval-christmas-the-boar-s-head-festival/

https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/occasions/christmas/coventry-carol-lyrics-meaning-history/

https://www.britannica.com/art/Lord-of-Misrule-English-medieval-official

https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/christmas/the-history-of-father-christmas/