My children love Edith Nesbit’s books. I love them too! I remember reading them when I was younger, and now my children listen to them in the car on the way home from school.

You’ve probably heard of some of her books, even if you haven’t read them: The Railway Children is probably her most famous, but she also wrote Five Children and It, The Phoenix and the Carpet, The Story of the Amulet, and The Enchanted Castle (as well as many, many others!)

At the time Edith was writing, over 100 years ago, she was just as famous as any best-selling children’s author today. Children awaited each new book eagerly–and with good reason.

Edith had a ferocious imagination, writing stories full of magic, adventure and drama, and she understood how children think: what they love, fear and desire.

Her depiction of sibling relationships is note-perfect, capturing the little jokes and quarrels that exist between brothers and sisters, as well as the fierce loyalty that can turn in an instant to bitter hostility, then back again in the next second!

You may be wondering why I am writing about Edith Nesbitt. Well, as it turns out she lived for a while not very far from where I live now – in Eltham in south-east London!

Her home was a place called Well Hall, an 18th century manor house which was built on the remains of a much earlier, medieval manor house of the same name.

Interestingly, there were two manor houses recorded in Eltham in 1100: East Horne and Well Hall. Neither manor is still standing (unfortunately) but their names remain.

Well Hall gives its name to Well Hall Road and Well Hall Pleasaunce – a sort of small park or garden – and East Horne manor lives on in the neighbourhood of Horn Park, which is in fact where I live!

As I said, the original medieval Well Hall manor was pulled down and rebuilt in the 18th century, but the barn that was built next door in the Tudor era remains, and is home to the Tudor Barn restaurant today.

Edith Nesbit lived in Well Hall from 1899 to around 1920. During this time she wrote many of her most famous novels, including the ‘Psammead Series’ (Five Children and It; The Phoenix and the Carpet; The Story of the Amulet), The Railway Children and The Enchanted Castle.

If you visit Well Hall Pleasaunce today (as I did) you’ll find some lovely wood carvings of the Psammead (the sand fairy from Five Children and It), the Phoenix (the magical fire bird from The Phoenix and the Carpet) and a dragon in honour of the many magical creatures Edith Nesbit wrote about.

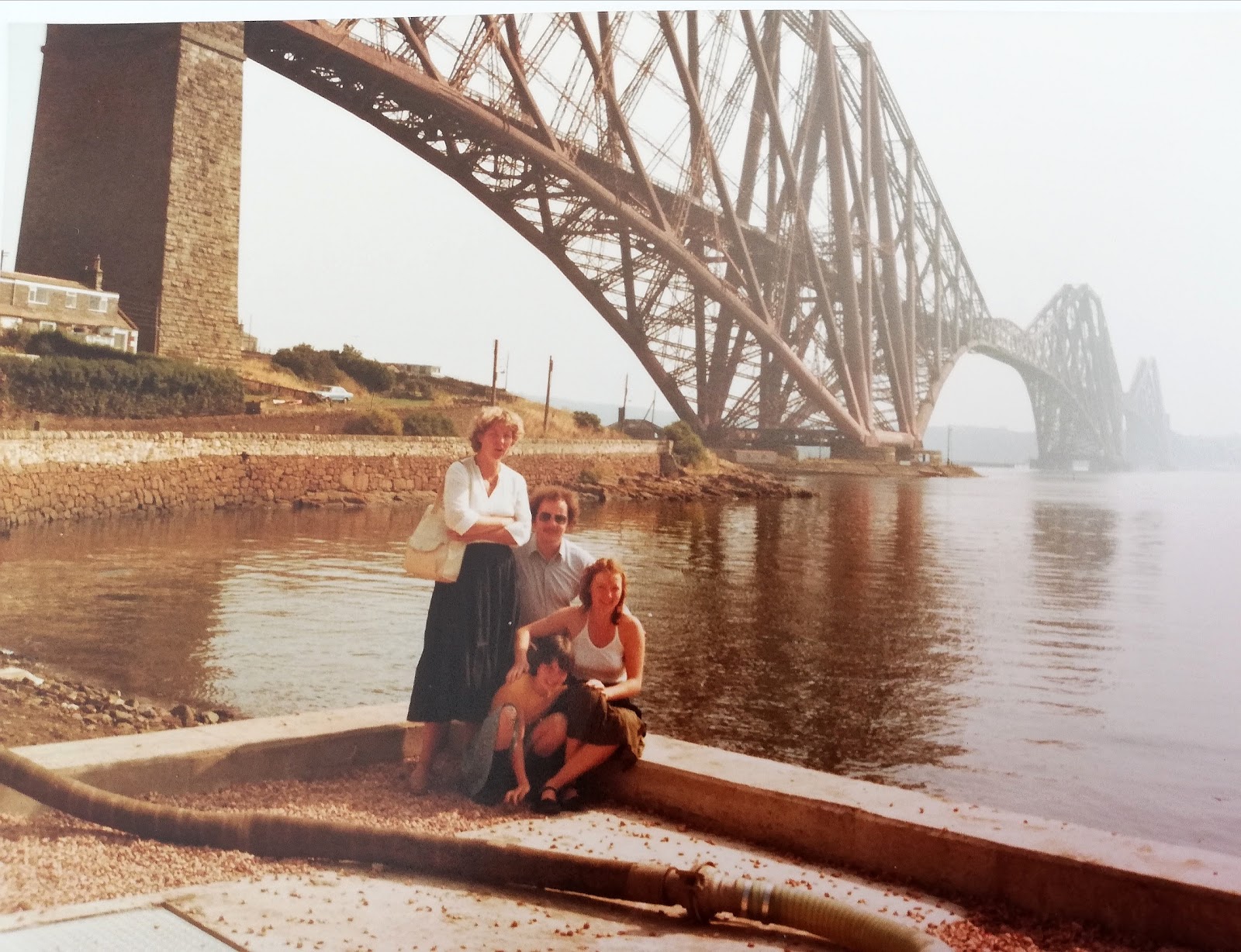

I had a great time walking in Edith’s footsteps (you can see my outing in the video that goes with this blog post). It was wonderful to walk where she would have walked, and to think what she might have seen and smelled and heard when she lived there.

The place would have been a lot quieter, with no main road, much fewer shops, and the whole place consisting of a small village in the countryside rather than a busy London suburb.

Despite these differences, however, it was very moving to have that connection to someone who was so influential in children’s writing.

Later in the day I visited Railway Children Walk in nearby Grove Park. It’s not much – just a narrow footpath behind some houses, leading to a bridge over a railway line – but as I walked down I had the sensation of walking away from the bustle of London and into a quiet place all by itself.

It was as if I was walking back in time to that period when there were fewer cars and no planes, no mobile phones and no internet. Back, in fact, to the era of The Railway Children, when trains ran on steam and the two World Wars hadn’t happened yet.

It reminded me that history isn’t confined to the past: it’s all around us. Sometimes it’s hidden, and you have to go digging for it; but sometimes you’ll come across it quite suddenly and unexpectedly.

It’ll be there in a place name, a street sign, a plaque on a wall or a rise in the ground. If you don’t know what it is you’ll probably miss it – but if you go out in your local area with an idea of what to look for you’ll find the past rushing up to meet you.

With that in mind, here’s this week’s Writing Challenge. In fact it’s not so much a challenge as an adventure!

Your challenge is to find out about a person who lived in your local area a long time ago, and see if you can find anything of them left behind, and record it on the sheet. They don't have to be very famous, but it would be good to know if they did something important or helpful.

You might not find much. It might just be a street name; it might be a house where they lived; it might be a path they used to walk along. Whatever it is, see if you can find it, and either draw it or take a picture.

Then write a description of the place as it might have looked when that person was alive. If it was long enough ago it might have changed a lot – or it might not have changed at all! Either way, it’s fascinating to think about how the past relates to the present. Include the person in your scene if you can.

Enjoy the activity, and happy time tunnelling!