The reason I’m telling you this is because I want to talk a bit about the setting for the story. It takes place in the Tudor period – during the reign of King Henry VIII – and it’s mostly set in a grand manor house or hall, which I’ve called Lockwood Hall.

Lockwood Hall is fictional – I made it up – but it’s based on a very real place called Haddon Hall in Derbyshire. It’s quite a famous Tudor manor house, and brilliantly preserved. If you go there today you’ll find parts of it looking much as they would have 500 years ago - and I definitely recommend you visit if you can!

|

| Haddon Hall, near Bakewell, Derbyshire (Image: Rene Cortin, Wikimedia Commons) |

When I was researching the book I looked at a lot of photographs of Haddon Hall, and planned out where various parts of the story would happen (in my version, Lockwood Hall). My main character, Grace, is a visitor to the hall, so there was plenty of opportunity for her to find her way around and explore the various nooks and crannies along with the reader.

Here’s how I describe Lockwood Hall the first time Grace sees it:

“The Hall was vast; hardly a house at all, but more like a small village, with a dozen halls and buildings sprawled over half an acre and a high wall running all the way around. Tall roofs bristled with chimneys, red brick shone ruddy in the sunlight, and rows of glazed windows flashed and gleamed.”

You’ll notice I’ve picked out three distinctive features of these great Tudor houses:

1. Brick walls. Go to any Tudor palace from the time of Henry VIII (such as Hampton Court Palace) and you’ll see they were beginning to be made of bricks rather than stone. Haddon Hall is a mixture of the two, as it was built in the late medieval period, just before the Tudor period.

_07.jpg) |

| Hampton Court Palace (Image: DiscoA340, Wikimedia Commons) |

2. Chimneys. Tudor palaces were famous for the number of fireplaces, each one served by a chimney. Fireplaces replaced the open hearth, and were more efficient and safer. Again, look at Hampton Court palace and you’ll see just how it ‘bristles’ with chimneys!

3. Glazed windows. Glass windows were still very much for the rich, and tended to be ‘mullioned’ – this means the panes of glass were very small, and joined together with strips of lead, often in a diamond shape. Poorer people still had open windows without any glass in them, and would have shutters that could be closed for warmth and privacy. Lockwood Hall also has stained glass windows in its main hall, which you would usually find in churches.

I think I’ve also made Lockwood Hall much larger than the real-life Haddon Hall – but I like to think that this is how it appears to Grace rather than it being the reality! We all know how big and confusing large buildings can seem on our first visit.

Here are some of the places that Grace comes across in the story, and the kinds of things that would have happened there.

Courtyard

|

| Haddon Hall lower courtyard and front door. (Image: Rob Bendall, Wikimedia Commons) |

In Lockwood Hall, the courtyard is the hub of all outdoor activity. It’s where visitors are received and groups of people prepare to ride out to hunt or visit local towns. Only the wealthiest Tudor families had enclosed courtyards – many manor houses were built in an E or H shape, with open spaces to the front or back.

Houses would have been self-sufficient, with everything the family needed provided on-site. This meant not just cooks and kitchens, but a blacksmith, a carpenter (or two), farriers (who took care of the horses’ feet specifically), dairy workers, launderers and more, all amounting to a small army of servants who kept the house and the family going.

In Lockwood Hall I’ve placed these trades around what is called the Lower Courtyard. This is probably a bit unrealistic, as the family wouldn’t want important visitors to be confronted by the sight of chickens being plucked! But it gives the house a real sense of life, so I’ve used some artistic licence.

Great Hall

|

| Christmas revels in Haddon Hall (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

Through the huge front door is a small antechamber (literally a ‘before-room’) where guests might wait to see the lord of the manor. Just off the antechamber is the Great Hall.

Coming out of the medieval period, the hall was still the absolute heart of any great Tudor home. This was where most of the life of the house took place: servants ate and even slept here, visitors were received and entertained, and the enormous room was filled with people and activity from dawn until dusk.

|

| Haddon Hall Great Hall today (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

In smaller houses floors were of packed earth; in the case of Lockwood Hall it is stone. Rush mats were laid down for warmth and cleanliness, like a huge, stiff carpet laid down in sections. Trestle tables could be put out and cleared away quickly, along with benches and stools for guests to sit on and eat. Tapestries hung from the walls provided insulation and a riot of colour. An enormous fireplace would have provided warmth (along with a considerable fire hazard!)

|

| Haddon Hall Great Hall fireplace (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

Much of the action in the book takes place in the Great Hall – there are feasts, celebrations, homecomings, and even some hostage-holding!

Parlour

|

| Haddon Hall parlour (Image: Elliott Brown, Wikimedia Commons) |

Just off the Great Hall is a smaller room called the parlour. This is where the family would have received visitors more privately, and sometimes have eaten their meals together away from the noise and bustle of the hall.

The parlour in Lockwood Hall (as in Haddon Hall) is wood-panelled, with a generous fireplace. It would have been a warm and comfortable place to sit in the long winter evenings!

|

| Haddon Hall, two carved figures in the parlour (Image: Michael Garlick, Wikimedia Commons) |

It’s in this parlour that Grace first meets the Lockwood family – her aunt and cousins. She returns later in the book for two more important confrontations, where she is faced with a choice each time: betray someone else to save her skin, or stay loyal and end up in trouble or worse!

Chapel

|

| Haddon Hall chapel (Image: John Salmon, Wikimedia Commons) |

Back out the front door and across the courtyard is the chapel. Religion was the lifeblood of Tudor existence – everyone believed in God (to a greater or lesser extent) and everyone went to church. Rich families would have their own chapel for private worship, and for their staff and servants to use to take the mass – bread and wine that represented the body and blood of Jesus Christ (and which most people believed became the actual flesh and blood of Jesus by a miracle called ‘transubstantiation’ – try saying that seven times fast!)

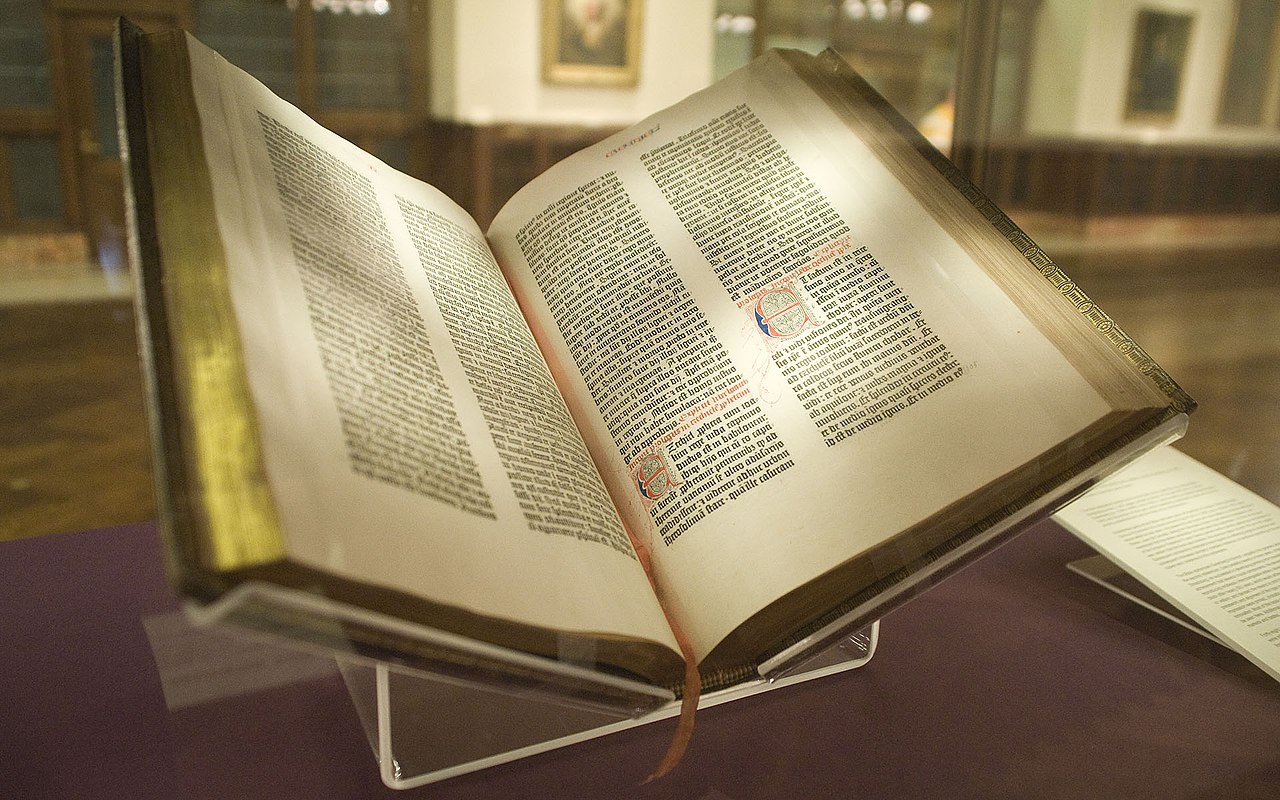

At the time my book is set – 1527 — religion was undergoing enormous upheavals all across Europe. A movement that became known as the Reformation was underway, in which people were beginning to question the absolute authority of the Roman Catholic church, and instead turning to their own reading of the Bible to understand how God wanted them to lead their lives.

|

| Martin Luther protesting against Catholic teaching, 1517 (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

This was a monumental change, and it was enabled by the translation of the Bible into the common languages that people read at the time: German, French, English and others. Until that time, in England, people had only ever had access to the Bible in Latin, and had relied on the priests and other church officials to explain it to them. Some people had translated the Bible into English around a hundred years before, but the practice had been outlawed and many of those Bibles burned.

_(14760920276).jpg) |

| Bibles being burned, from 'Foxe's Book of Martyrs' (Image: Wikimedia Commons) |

In 1527, owning an English Bible – or even just reading one – was still illegal, and people who did were at risk of being arrested and executed for heresy and treason. The Lockwood family in my book are Reformation supporters, and so (to the surprise of Grace) they hold their worship services in English rather than Latin – that is, until a certain guest turns up …

Those are just some of the locations that feature in ‘Through Water and Fire’. There’s also a tense confrontation in a garden, a shocking slap in a bedroom, and a secret tunnel leading to a very mysterious location – but I don’t have time to go into that now. You’ll just have to read the book!

Writing challenge

I hope you’ve enjoyed learning about some of the places in a Tudor house. I really enjoyed travelling through the hall in my mind and deciding what would happen where.

For your writing challenge this week I want you to do the same! You have two choices:

1. Download the map of Lockwood Hall, and plan out your own story of someone arriving at the house and discovering a thrilling secret. Maybe someone has got their hands on an illegal English Bible and is on the run from the law! Think what the purpose of each of the locations was, and plan your story around that.

|

| Lockwood Hall. Right-click on the image to download and print it. (Image: Noami Berry, Wakeman Trust) |

2. Draw a map of a building you know well. It could be your home, or your school. Plan out a story that takes place in every room. Think about what is in each room that you could use as part of the story. Maybe even add a secret passage of your own …!

Enjoy your writing challenge, and happy Time Tunnelling!

About the author

Matthew Wainwright is an author of children's historical fiction, and a member of the Time Tunnellers. His first book, 'Out of the Smoke' is set in Victorian London and was inspired by the work of Lord Shaftesbury with chimney sweeps and street gangs. His second book, 'Through Water and Fire', is set in Tudor England and features Anne Boleyn and the English Reformation.

For more information on Matthew and his books, visit his website: matthewwainwright.co.uk

You can buy 'Through Water and Fire' online, or from your local bookshop. Buy here.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)