I have long harboured an ambition to visit the wonderfully eccentric Gothic Revival villa of Strawberry Hill House in Twickenham, the creation of writer, art-historian and politician, Horace Walpole (1717-1797).

I read

Walpole’s The Castle of Otranto,

generally regarded as the first gothic novel, in the sixth form at school and I

was keen to see what else his imagination had conjured into life in bricks and

mortar.

My visit, in

late August, coincided with the final weeks of a fascinating exhibition of late

Regency and Victorian toy theatres, many of which took as inspiration the

gothic melodramas that were so popular on the English stage in those days.

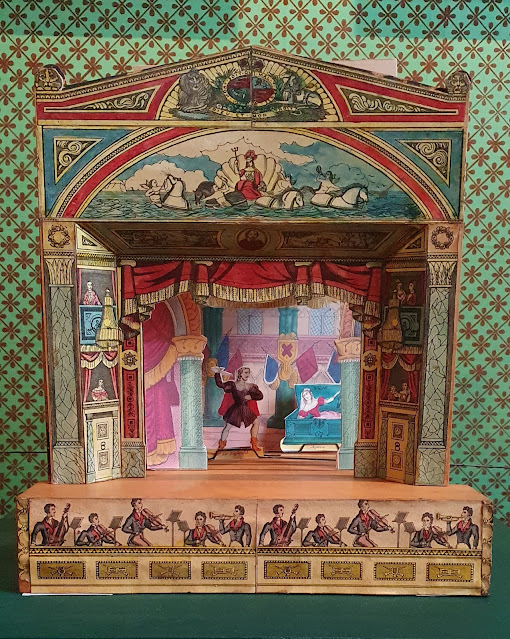

A toy theatre of the play, ‘Blue Beard’ by George Colman, dating from

around 1862/3

The

exhibition was staged by Strawberry Hill in association with Pollock’s Toy Museum in London who own an extensive collection of toy theatres

dating back to the days of Benjamin Pollock, a publisher and seller of

everything needed to put on performances of plays in miniature in your own home.

As I peered

beyond the proscenium arch into the tiny worlds depicted on stages built from

wood, cardboard and paper, I was transported back to a time when plays were the

main form of dramatic entertainment, long before the world of film and

television came to dominate visual storytelling.

Though

people made their own toy stages and enjoyed putting on puppet plays, it wasn’t

until 1811 that the first commercially-produced toy theatres, also known as

paper theatres, began to be made.

With origins

in the theatrical souvenir prints first produced by print publishers in Covent

Garden, London’s main theatre district, they sought to replicate the popular

theatre productions of the day. These were melodramas, pantomimes, folkloric

tales and ballad opera, all of which involved plenty of action, scenery changes

and more than a little blood and gore.

Scene from the popular melodrama, The Miller and His Men, or The Bohemian Banditti by Isaac Pocock dating from circa 1862

At first the toy theatre kits were quite limited in scope, made up wooden stages with a few sheets of characters and a selection of scenes. But as their popularity and that of theatre-going itself grew, they became more complex offering complete scenes, a wider range of characters – with costume changes – and scripts based on the plays being presented on stage, cut down to make them easy to present at home. There was even the chance to buy tiny candles and oil-lamps to light the stage too – a risky business when everything was made of wood, card and paper!

The characters and sets were drawn by professional artists including George Cruikshank who went on to illustrate the early editions of many of Charles Dickens’ novels. The artists modelled their work closely on the stage play and were usually given a free seat to make their sketches from life. They even gave the paper version of the actors they drew the same facial expression as the real-life ones. Copies of the original drawings were then printed on to paperboard for sale.

During the

first half of the 19th century 300 of London’s most popular plays

were issued as toy theatres and many of them were sold in theatre foyers to

members of the audience attending the show as mementoes of their visit as well

as playthings for their children. Theatre-owners loved them too because they

acted as great free advertising for their shows.

Popular

play-kits included Blue Beard, based

on the original, grisly French fairy-tale about a man who kills his wives and

locks them away in a secret chamber, The

Mistletoe Bough, a chilling story about a girl who gets locked in a chest

while playing a game of hide-and-seek at Christmas and The Miller and His Men. This, the most popular toy-theatre

melodrama of its day, a tale of kidnap and robber-bandits hiding out in the

forest, came complete with a small wad of gunpowder for lighting in the final fight

scene (see image above). Shakespeare’s

history plays were also a popular subject as were the pantomime stories of The Forty Thieves, Aladdin and Sleeping Beauty.

A scene from The Mistletoe Bough; or, The Fatal Chest, a

melodrama by Charles A. Somerset shown at the Garrick Theatre in 1834. Toy

theatre version circa 1859

The typical

price for a sheet of characters or scenery was “a penny plain and twopence

coloured”. The word ‘plain’ referred to sheets printed in black and white. The

‘coloured’ sheets sold were pre-coloured, sometimes by hand.

Aside from the fact they were cheaper, there was great fun to be had from buying the ‘plain’ sheets as you could colour the stages and characters yourself. For either type, you could add extra decorative touches using bits of cloth and ‘tinsel’ (pieces of metal foil). You then cut the characters out and mount them on small sticks, wires or strings for moving around the stage as you spoke the lines.

The actual

theatre ‘boxes’ the plays were staged in could be made at home or else bought

in shops. The latter were quite large and elaborate and the more costly ones

even had roll-up curtains. And no toy theatre was without its own orchestra

pit!

Behind the scenes of a toy theatre

Not

surprisingly, adult toy-theatre enthusiasts of the day included several authors

of children’s stories including, Lewis Carroll, Hans Christian Andersen, Oscar

Wilde and Robert Louis Stevenson. Stevenson loved them so much he even wrote about them.

The

author of many children’s books, Robert Louis Stevenson was a great fan

The heyday

for toy theatres was from the early 1830s to the mid 1860s. After this time,

few new titles were added and the move towards more ‘realistic’ plays in the theatre

proved less-suited to the medium. The number of toy theatre publishers began to

dwindle and, after 1890, there were only two main publishers of toy theatre

kits – H.J. Webb and Benjamin Pollock. Pollock kept trading until he died in

1930. His stock was eventually bought up by an enthusiast and went on to form

the basis of the collection now owned by Pollock’s Toy Museum.

Some Shakespeare plays were also

adapted for toy theatre.

This picture shows a close up of a scene in Richard

III

If you want

to marvel at these small miracles yourself and are planning a visit to London

in the near future, then, in the words of Robert Louis Stevenson: ‘If you love art, folly, or the bright eyes

of children, speed to Pollock’s ...’ Or alternatively, check out their toy theatre page online including a great short video

on how to put on a toy theatre play.

Let the play

begin!

Watch Ally's You Tube video on toy theatres by clicking here

Ally Sherrick is the author of books full of history, mystery and adventure including Black Powder, winner of the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award 2017, The Buried Crown and Tudor-Set adventure, The Queen’s Fool. She is published by Chicken House Books and her books are widely available in bookshops and online. You can find out more about her and her books at www.allysherrick.com and follow her on Twitter: @ally_sherrick