The national tourism organisation for Scotland, VisitScotland, has since 2009 been running themed years to celebrate aspects of Scotland – its people, culture and heritage – that deserve recognition. 2022 has been designated Scotland’s Year of Stories and, as an author with a passion for history, this past year has provided a number of opportunities for me to explore the intersection of local history and archaeology, and the stories they inspire.

My love of the past began as a child on frequent visits to Kirkintilloch’s Auld Kirk Museum, which housed a collection of historical objects such as Roman soldiers’ uniforms and household items through the ages. Staff also put considerable effort into engaging children through activity days and, growing up, I got to try out everything from traditional crafts such as carding wool, spinning and weaving to attempting shoemaking on a cobbler’s last.

These visits sparked lots of story ideas which I scribbled down on bits of paper with hand-drawn illustrations, stapling them together to form my first ‘books’ which usually ended up in the bin when a better idea came along. There was one story idea that stayed with me for many decades, however, inspired by my memorable year in primary four when I was eight, when I learned about the poems of Robert Burns for the first time. That year we read Tam o’ Shanter, and I still remember the thrill of hearing the spine-tingling tale of witches through the medium of Scots poetry and learning about the early life of Burns and the world he grew up in.

The story of witches dancing to the devil’s music in the Auld Kirk at Alloway stayed with me, and when I turned to Scottish stories for inspiration for my books as an adult, that was the first tale that jumped straight into my head. Researching the life of Burns, I came across accounts of the young Burns hearing folktales of kelpies, wraiths and bogles round the kitchen fire, and I could imagine him being just as spellbound by the stories he was told by adults as I was as a child. That got me thinking about a fictional account of how his own adult poem Tam o’ Shanter could have been inspired by a childhood encounter with witches in the Auld Kirk. The story of Hag Storm is therefore a metafiction of the young Rab having a spooky Halloween experience which later becomes the basis of his own supernatural poem.

But it isn’t just books, poems and my own childhood experiences which I’ve drawn on to come up with my own novels. As a member of Archaeology Scotland, I’ve been lucky to have had the chance to get involved in local archaeological digs, and over the past year have got out and about in Denny, near Falkirk, and Cathkin Park, Glasgow, exploring Scotland’s past. Not only do community digs like these teach volunteers the basics of field excavation – from topsoiling, mattocking, trowelling and surveying techniques, to cataloguing finds and interpreting evidence – they also give us the opportunity to experience history in a hands-on way which is very different from the experience of reading about it in a book. I’ve been amazed on these digs just how exciting it is to uncover little pieces of the past, no matter how small or seemingly insignificant-looking. Bits of broken china, glass and bent nails can seem every bit as thrilling a find to an amateur historian like me as digging up stashes of Roman coins or a new dinosaur bone is to a professional. Uncovering the foundations of strike-breakers’ houses in Denny and the original Third Lanark football team baths and changing rooms in Cathkin Park were wonderful experiences, and it felt to the volunteers like we’d found our very own ancient Egyptian tomb or Mayan pyramid.

Uncovering the foundations of strike-breakers' houses in Denny

One of the best things about engaging in local archaeological digs is getting the chance to hear the stories told by excavators, volunteers and visitors to the digs sites about their own experiences of the site as children, or about their ancestors’ experiences. Visitors to the Denny dig site who looked at the displayed ‘Virol bottle’ we’d found recalled being given Virol as a supplement, either by their parents or at school. Passers-by and museum staff at the Jimmy Johnston Academy at Cathkin Park recounted tales of their visits to the football stadium when it was still standing and shared their memories of their time in the park as children. The finds at these sites represented real links not just to the past buried under a layer of ash at Milton Row in Denny and years of soil and infill at Cathkin Park, but to the childhoods and lived experiences of local residents who took part in these digs or who visited the sites. It also emphasised for me the ability of community archaeology to connect the everyday experiences of people alive today to those who lived in the past.

Victoria using a mattock to remove the soil from an excavation area in Cathkin Park, Glasgow

Archaeology Scotland has long been providing fantastic opportunities such as these for volunteers to engage in local digs and find out all about the history on their doorstep. My own journey as an author was started in childhood by enthusiastic historians who passed on their knowledge and encouraged me to explore all of the stories my local area had to offer. But it’s not just children and young people whose imaginations can be sparked by local digs, and whose early experience of history and archaeology might set them on the path to becoming the authors of the future. It’s never too late to embark on your writing adventures, so why not get involved in one of Archaeology Scotland’s digs in this Year of Stories, and see what local tales you can uncover?

Writing Challenge

Imagine you find a hag stone, either by a river or by the sea. Have a think about the location where you find it – can you describe it? Is it by running water in a deep, dark forest? By a stream in a sunlit glade? By a stormy sea with wind-tossed waves? On a sandy beach with warm waters lapping at your toes? See how many interesting adjectives you can use to describe the place where you find your hag stone, as where you find it might just influence what you see through the hole!

Now…

Put the hag stone to your eye and look through the hole. What do you see?

Describe the ‘other world’ that you can see through the hole. This place can be anything you like – a fantasy world, a futuristic science fiction world, funny, spooky, scary, weird or magical – it’s up to you! I’d love to read your hag stone tales, so do get in touch on Twitter or through my website to show off your writing!

Watch Victoria's YouTube video by clicking here

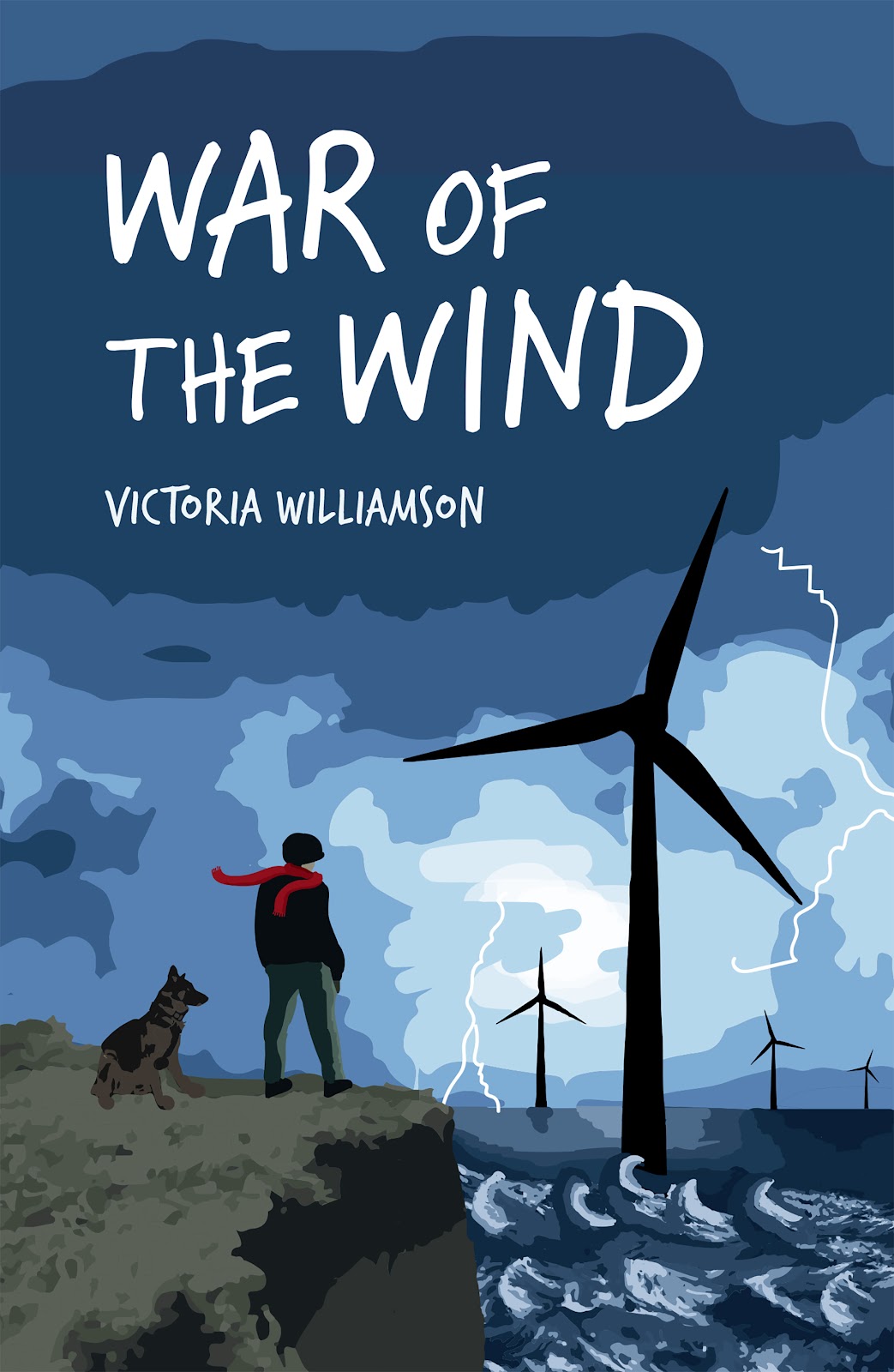

Victoria Williamson is a children’s author who grew up in a small town north of Glasgow, surrounded by hills and books. She started writing adventure stories from an early age, with plots and characters mostly stolen from her favourite novels and TV shows! These days the stories are all her own, featuring the voices of some of the many children she’s met over the years on her real-life adventures around the world.

Victoria was a teacher for many years, working in all sort of exciting places from Cameroon, Malawi and China to the UK. She now divides her time between writing and visiting schools and literacy festivals to talk about books and run creative writing classes.

Website: www.strangelymagical.com

Twitter: @strangelymagic