March is Women’s History Month when we celebrate the lives and achievements of women throughout history.

Until comparatively recently, most history was about men. After all, broadly speaking, men were the rulers, the law-makers, the generals and the scholars. Men were the ones who did things and history was about what they did. And most history was written by men too.

Thankfully, things have changed dramatically and we now know a lot more about the lives and achievements of women. However, it is still true that the further back in history you go, the harder it is to find women who are remembered in their own right, and not just for being the mothers, daughters or wives of famous men. The obvious exception is powerful female rulers, like Cleopatra and Queen Elizabeth I.

But there were other remarkable women from long ago who made their mark on history in their own right and left behind the evidence to prove it. Prominent among these were the early Christian female saints.

I’m going to tell you about two of them. Their names were Perpetua and Felicity.

Perpetua and Felicity lived more than 1800 years ago, at the beginning of the third century AD. They lived in North Africa, in a place called Carthage, which at the time was in the Roman province of Africa, and today is in Tunisia. Vibia Perpetua was 22, a well-educated noblewoman with a young son, probably a widow. Felicity was a slave, pregnant with her first child. At the time, Christians in this part of the Roman Empire faced persecution, yet both of these women bravely decided to become Christians, and as a result were arrested, imprisoned and put to death.

But the most remarkable thing about this – and why we know so much about it - is that Perpetua left behind a diary, a document now known as The Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity. This is one of the earliest surviving first-person narratives written by a woman.

Apparently, Perpetua’s mother had been a Christian, but her father was not, and in her diary she writes of how he pleaded with her to change her mind. She wouldn’t do so, and both women were arrested and imprisoned.

Perpetua describes the terrible heat of the prison (this is north Africa, remember) and the rough behaviour of the guards. She also writes about how upset she is at having to leave behind her baby, including the physical torment caused by the fact that she abruptly has to stop breast-feeding him. When she is allowed to continue breast-feeding, after bribing the guards to move her to a better part of the prison where he can be with her, she writes of the great relief and happiness she feels.

At a hearing in front of the Roman Governor, Perpetua and Felicity both refused to give up their Christian faith and were therefore condemned to public execution by means of wild beasts. Both women, along with three Christian men, were to be put to death at the military games held in Carthage to celebrate Emperor Septimius Severus’s birthday. Perpetua’s record of her trial and imprisonment ends the day before the games.

The column in the centre is a memorial to the Christian martyrs

‘Of what was done in the games themselves, let him write who will,’ Perpetua writes. The diary was finished by an eyewitness, who relates that Felicity gave birth to a daughter before the games, which meant that she could join Perpetua in her martyrdom. (Roman law forbade pregnant women to be put to death.) Arrangements were made for Felicity's daughter and Perpetua's son to be cared for after their deaths.

If you have read Vita and the Gladiator by my fellow Time Tunneller, Ally Sherrick, you will have a sense of what Perpetua, Felicity and their male counterparts experienced when they walked into the Roman arena. The eyewitness account emphasises how bravely they faced their deaths, entering the arena with their heads held high, so strong was their faith in God. The men sentenced to die alongside Perpetua and Felicity were attacked by bears, leopards and wild boars, Perpetua and Felicity were set upon by a rabid cow. But the wild beasts failed to kill them, and they were put to death by sword.

Perpetua and Felicity have been revered as saints ever since their deaths, and they are still remembered in all branches of the Christian church today. In life they were separated by social class - Perpetua was a noblewoman and Felicity a slave - but they died together as sisters, which would been a powerful witness to their status-conscious contemporaries as to the radical nature of the Christian faith. Their feast day, on which they are especially remembered, is 7 March.

It is remarkable to think that, in St Perpetua’s account of her imprisonment, we can read the voice of someone who lived over 1800 years ago.

Watch Catherine's YouTube video about St Perpetua and St Felicity by clicking here

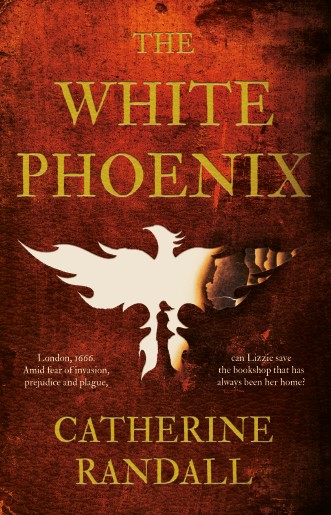

Catherine Randall is the author of The White Phoenix , an historical novel for 9-12 year olds set in London, 1666. It was shortlisted for the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award 2021. Catherine is currently working on a children's novel set in Victorian London.

The White Phoenix is published by the Book Guild and available from bookshops and online retailers.

For more information, go to Catherine’s website: www.catherinerandall.com.