Wednesday, 19 June 2024

William Shakespeare Part 2: London - Another Classroom Activity

Thursday, 14 March 2024

A Chilly Afternoon's Mudlarking! by guest author Kate Wiseman

Hi, I was absolutely delighted to be asked to make a film about mudlarking* for the Time Tunnellers.

If you don’t know, mudlarking is searching the Thames foreshore at low tide to see what historical treasures you can find, and you need a permit from the Port of London Authority to do it. I’m always more than happy to talk about mudlarking, so I set off on a chilly late winter’s day to see what the Thames would give me.

The tide wasn’t particularly low, but the Thames was generous, as she usually is. My favourite finds were a tiny 17th century pipe bowl and a lovely nugget of fool’s gold. Someone suggested that I break it open to see what it’s like inside, but I think it’s beautiful as it is. What do you think?? What would you do?

One of Kate's mudlarking finds

I didn’t come across my dream find: a bellarmine jug or

witch bottle. They were used in the 17th century to ward off

witchcraft. Superstitious people filled them with nail clippings, hair, red

thread and even urine to counteract witches’ spells. Often they would be buried

under the doorway of a house, or beneath the fireplace. Others were simply used

to transport alcohol and thrown into the Thames when empty.

I did find the handle of one, and also the eye from the representation of an angry-looking man. These were applied to the front of bellarmine bottles. I dream about finding a whole one and if I ever do, I’ll be shouting about it from the rooftops.

the original mudlarkers were poor children.

My first Mudlark Mystery, The Grinning Throat, features a witch bottle and on the front cover, Edie Lighterman, one of my protagonists, is shown holding one. That will have to do until I find a real one. Watch this space…

'My first thought is that it’s a pig that someone has lost to the river. Perhaps it fell off one of the barges that choke up the Thames. They’re a constant feature, toiling up and down, day and night, giving off black smoke that clings to the water.'

Joe (15) and Edie (13) are orphans living in Victorian London. Forever worried that they will be sent to the dreaded workhouse, they scratch out a living the best way they can by mudlarking on the foreshore of the River Thames and selling their finds to the notorious Hempson. One day they discover something macabre, and it will change their lives forever.

The Grinning Throat is the first in the trilogy of The Mudlark Mysteries. Written by award winning author, Kate Wiseman, it is historical fiction at its best. Suitable for readers from age 9 and upwards.

The Grinning Throat has been longlisted in the historical Association's Young Quills 2024 award.

You can buy copies online HERE.

Find out more about mudlarking and Kate's other books at Katewiseman.co.uk

*Mudlarkers in London must have a Thames Foreshore Permit which can be obtained from the Port of London Authority. All objects which are three hundred years old or more must be reported to the Museum of London. Mudlarks arrange regular appointments with a Finds Liaison Officer who records the artefacts on the Portable Antiquities Scheme managed by the British Museum.

Wednesday, 31 January 2024

Local Legend Edith Nesbitt, with Time Tunneller Matthew Wainwright

My children love Edith Nesbit’s books. I love them too! I remember reading them when I was younger, and now my children listen to them in the car on the way home from school.

You’ve probably heard of some of her books, even if you haven’t read them: The Railway Children is probably her most famous, but she also wrote Five Children and It, The Phoenix and the Carpet, The Story of the Amulet, and The Enchanted Castle (as well as many, many others!)

At the time Edith was writing, over 100 years ago, she was just as famous as any best-selling children’s author today. Children awaited each new book eagerly–and with good reason.

Edith had a ferocious imagination, writing stories full of magic, adventure and drama, and she understood how children think: what they love, fear and desire.

Her depiction of sibling relationships is note-perfect, capturing the little jokes and quarrels that exist between brothers and sisters, as well as the fierce loyalty that can turn in an instant to bitter hostility, then back again in the next second!

You may be wondering why I am writing about Edith Nesbitt. Well, as it turns out she lived for a while not very far from where I live now – in Eltham in south-east London!

Her home was a place called Well Hall, an 18th century manor house which was built on the remains of a much earlier, medieval manor house of the same name.

Interestingly, there were two manor houses recorded in Eltham in 1100: East Horne and Well Hall. Neither manor is still standing (unfortunately) but their names remain.

Well Hall gives its name to Well Hall Road and Well Hall Pleasaunce – a sort of small park or garden – and East Horne manor lives on in the neighbourhood of Horn Park, which is in fact where I live!

As I said, the original medieval Well Hall manor was pulled down and rebuilt in the 18th century, but the barn that was built next door in the Tudor era remains, and is home to the Tudor Barn restaurant today.

Edith Nesbit lived in Well Hall from 1899 to around 1920. During this time she wrote many of her most famous novels, including the ‘Psammead Series’ (Five Children and It; The Phoenix and the Carpet; The Story of the Amulet), The Railway Children and The Enchanted Castle.

If you visit Well Hall Pleasaunce today (as I did) you’ll find some lovely wood carvings of the Psammead (the sand fairy from Five Children and It), the Phoenix (the magical fire bird from The Phoenix and the Carpet) and a dragon in honour of the many magical creatures Edith Nesbit wrote about.

I had a great time walking in Edith’s footsteps (you can see my outing in the video that goes with this blog post). It was wonderful to walk where she would have walked, and to think what she might have seen and smelled and heard when she lived there.

The place would have been a lot quieter, with no main road, much fewer shops, and the whole place consisting of a small village in the countryside rather than a busy London suburb.

Despite these differences, however, it was very moving to have that connection to someone who was so influential in children’s writing.

Later in the day I visited Railway Children Walk in nearby Grove Park. It’s not much – just a narrow footpath behind some houses, leading to a bridge over a railway line – but as I walked down I had the sensation of walking away from the bustle of London and into a quiet place all by itself.

It was as if I was walking back in time to that period when there were fewer cars and no planes, no mobile phones and no internet. Back, in fact, to the era of The Railway Children, when trains ran on steam and the two World Wars hadn’t happened yet.

It reminded me that history isn’t confined to the past: it’s all around us. Sometimes it’s hidden, and you have to go digging for it; but sometimes you’ll come across it quite suddenly and unexpectedly.

It’ll be there in a place name, a street sign, a plaque on a wall or a rise in the ground. If you don’t know what it is you’ll probably miss it – but if you go out in your local area with an idea of what to look for you’ll find the past rushing up to meet you.

With that in mind, here’s this week’s Writing Challenge. In fact it’s not so much a challenge as an adventure!

Your challenge is to find out about a person who lived in your local area a long time ago, and see if you can find anything of them left behind, and record it on the sheet. They don't have to be very famous, but it would be good to know if they did something important or helpful.

You might not find much. It might just be a street name; it might be a house where they lived; it might be a path they used to walk along. Whatever it is, see if you can find it, and either draw it or take a picture.

Then write a description of the place as it might have looked when that person was alive. If it was long enough ago it might have changed a lot – or it might not have changed at all! Either way, it’s fascinating to think about how the past relates to the present. Include the person in your scene if you can.

Enjoy the activity, and happy time tunnelling!

Wednesday, 6 September 2023

Six Things You Never Knew About the Great Fire of London by Catherine Randall

Everyone knows about the Great Fire of London. When I go into Year 2 classes dressed as a bookseller from 1666, the children tend to know almost as much about it as I do, which says a lot about how well it is taught.

But when I wrote The White Phoenix, my novel for 9 to 12 year olds set in London 1666, I had to delve deeply into the history of the Great Fire of London and I found out lots of things that I hadn’t known before.

I thought you might like to know them too – so here are Six Things You Never Knew About the Great Fire of London!

1. It wasn’t the first Great Fire of London

If you’d talked to a Londoner in 1665 about the ‘Great Fire of London’, they would probably have assumed you were talking about the Great Fire of July 1212 – also called the Great Fire of Southwark. As its name suggests, this began in Southwark, just across the river from the City of London, at the south end of London Bridge. The fire destroyed most of Borough High Street and then began to spread across London Bridge, which at that time was covered with wooden houses and shops. To make matters worse, the wind blew embers across the river igniting the northern end of the bridge. Hundreds of people became trapped on the bridge – some fleeing the fire from the south, and some coming across from the north to help fight the fire. There are no reliable contemporary reports of the number who died, but a later historian suggested it could have been as many as 3,000. That seems very high, but whatever the truth, it is clear that many more people lost their lives in the fire of 1212 than in the fire of 1666.

There was another big fire in 1633 which destroyed premises on the northern third of London Bridge. You can see from this painting of the Great Fire of 1666 that there are no buildings on the north (left) side of the bridge. This is because these buildings had not been rebuilt after 1633, which proved to be a very good thing in 1666, because it created a firebreak on the bridge, preventing the Great Fire of London spreading to the opposite bank of the Thames.

2. England was at war!

In 1666, England was at war with two countries – the Netherlands and France. This was the Second Anglo-Dutch war, begun in early 1665, mainly due to rivalry over overseas trade. The stakes were raised in February 1666 when the French joined in on the side of the Dutch.

The war was fought mainly at sea, but all through the hot, dry summer of 1666 there was a very real fear of invasion. When the fire broke out, many people believed it was an act of war by the French or the Dutch, and that they'd deliberately set fire to the city. It meant that among all the chaos of people trying to save their houses and their possessions, mobs were going round attacking anyone thought to be French or Dutch. It was a terrifying time to be a foreigner on the streets of London.

3. The Mayor’s Nightmare...

Obviously, the big question about the Great Fire of London is how a city which was used to fires and had lots of procedures in place to deal with them allowed a fire to spread so far and so fast that it practically destroyed the whole city?

We’re taught lots of reasons for this – a hot summer, the wooden buildings all crammed together, a strong wind – but in fact there is one person who deserves to be better known, for all the wrong reasons: Sir Thomas Bludworth, the Lord Mayor of London.

The most important thing about controlling fires is to contain them straightaway. Sir Thomas Bludworth soon arrived at the scene of the fire, but he refused to let the firefighters pull down the houses on either side of Farriner’s bakery without the permission of the owners, and he didn’t know where the owners were because most houses were rented. So he just blustered and said the fire wasn’t as bad as all that, or words to that effect, and went home to bed. By the time he returned in the morning, the fire was out of control.

Both contemporaries and later historians consider Bludworth’s failure to contain the fire a crucial factor in its unprecedented spread.

4. Fire engine falls in the Thames!

Believe it or not, an early type of fire engine already existed at the time of the Great Fire, and there were several in London. Of course they were nothing like our modern fire engines, being basically pumps mounted on carriages. Sadly they were too large and too heavy to be of much help, and one of them even fell in the Thames!

5. A Frenchman was hanged for starting the Great Fire

A young French watchmaker called Robert Hubert confessed to starting the Fire by throwing a fireball through the window of Thomas Farriner’s bakeshop on the night of 1st/2nd September. It had already been established by the authorities that the fire had been started accidentally, and not maliciously, but Hubert insisted that he had done it and was brought to trial. When questioned, his story kept changing, he seemed to have no motive, and then it emerged that he hadn’t even been in London at the time. Nevertheless, he insisted that he had done it, and he was hanged for it.

Even at the time, this was seen as a bizarre miscarriage of justice, but for Londoners it did have a significant upside. When it came to the question of deciding who should pay for the rebuilding of London, the judges ruled that as the Frenchman Hubert had hung for it, the fire had legally been caused by an ‘enemy’, and therefore owners, not tenants, should pay for the rebuilding. Excellent news for ordinary folk!

6. The rebuilding

Despite many eminent people having lots of great ideas about new designs for rebuilding the City after the Fire, it was pretty much built on the same lines as pre-Fire London with the addition of one or two new streets. In fact, the layouts of the streets and buildings in the City of London didn’t change much until after the Blitz in 1940 during World War II.

WRITING CHALLENGE

After the Great Fire of London, there were appeals to towns and villages throughout the whole country to raise money to help the homeless citizens of London.

Imagine you are responsible for telling people in another town what has happened in London and why the city needs help. Can you describe what has happened and persuade people to give money? Your letter can be quite short, but you need to get some crucial information in there so that people realise just how much of a calamity it is, and how much of the City has been destroyed.

Catherine Randall is the author of The White Phoenix , an historical novel for 9-12 year olds set in London, 1666. It was shortlisted for the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award 2021. Catherine is currently working on a children's novel set in Victorian London.

The White Phoenix is published by the Book Guild and available from bookshops and online retailers

For more information, go to Catherine’s website: www.catherinerandall.com.

Wednesday, 21 June 2023

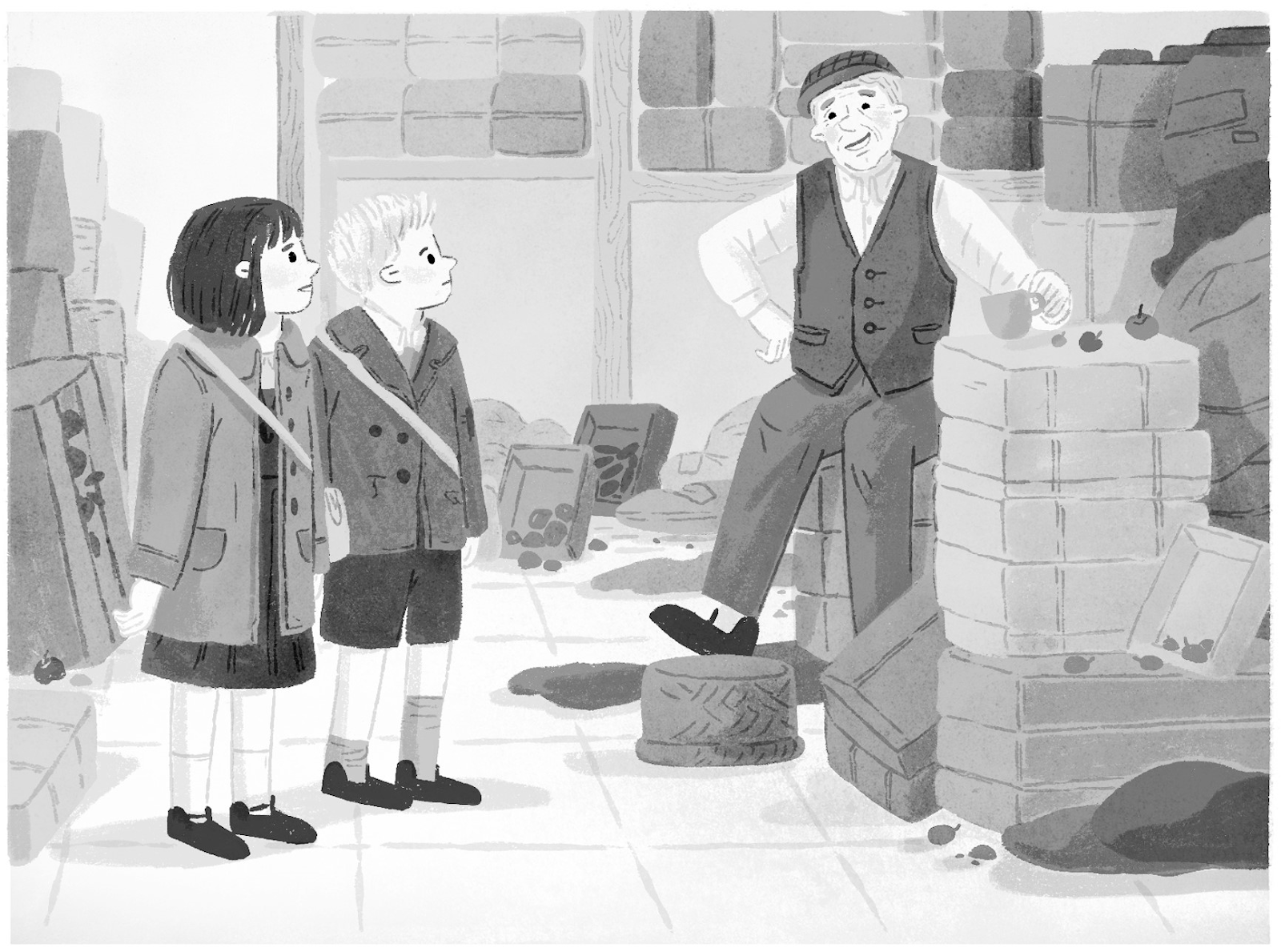

Operation Banana by Tony Bradman: a very personal view of the Second World War

The story of how a book comes into existence is often deeply rooted in its author’s life. For me that is particularly true of my book Operation Banana, published by Barrington Stoke. I’ve written a lot of books for them, including several titles set in either the First (Anzac Boys) or Second World War (Bruno and Frida). But with Operation Banana I really did go right back to the sources of my own career.

As the blurb for Operation Banana says, the story is set in the dark days of the Second World War. Its central character Susan is worried about her mum, who is struggling with long hours at a munitions factory and upset because they haven’t heard from Susan’s soldier dad for months. So Susan decides she’s going to cheer up her mum by getting her a treat - a sweet, delicious banana. But everything is in short supply in wartime London, so how on earth is Susan going to find one?

In many ways, Susan’s world was one I felt very familiar with, although I was born nine years after the war, in 1954. Like many people born in those early postwar years, history cast a long shadow over my childhood. My parents were born in the 1920s, and they often talked about living through the most difficult times of the 20th century - the Depression, the rise of Fascism and Communism, the Second World War.

They were in their early teens when the war started, and when it ended they were young adults, both in the Royal Navy. They were Londoners, so they lived through the Blitz and its terrors, and had plenty of stories to tell about those dark days. My Dad was on HMS Belfast and saw action in the North Atlantic and the Far East, and my Mum served in the naval base at Portsmouth during the D-Day landings.

Hearing their stories from an early age played a large part in getting me interested in history. By the time I was in my mid-teens I was a dedicated reader of historical fiction, but also of historical fact. Yet even though I came to know a great deal about the titanic events of the biggest, most destructive war in the history of the human race, because of my parents I always tended to see it from a personal angle.

Adolf Hitler might have wanted to conquer the world, but for my Mum and Dad that simply meant lots of day-to-day misery. If you read the memoirs of people who were children in the war, they remember the big events, but they often talk about basic things too, particularly all the rationing and constantly being hungry. Food is important to children, and in the war most children just didn’t get enough.

Mind you, some did, though. Both my parents talked about another aspect of the war that’s usually overlooked, especially by those who idealise the conflict in Churchillian terms as ‘Our Finest Hour’. For many people it was, but the crime figures soared too. The ‘Black Market’ did a roaring trade, and you could get pretty much anything if you knew the right dodgy geezers and had enough money.

It was also a long war. The story is set at the end of 1942, the mid-point, but as Susan says, at the time nobody knew how much longer it would last. Everyone was exhausted and fed up. Of course it was tough on the soldiers, sailors and airmen who were fighting. But it was hard on the people at home, especially mums with young families. They often had to work hard and take care of their children as well.

All of these things came together when I started writing. I’d realised there had been millions of people like my Mum and Dad, and like Susan and her mum. Ordinary people whose lives were turned upside down by the war, and who struggled to survive, to stay cheerful and help each other get by. They were just as important in winning the war, and that’s why I wanted to tell today’s children their story.

Barrington Stoke have done a great job in designing and producing the book, and it’s been wonderful to work with the illustrator Tania Rex again. Her illustrations have added an extra layer of warmth to the story, and it’s a delight to see how well she has brought Susan and the other characters of wartime London to life.

Operation Banana is dedicated to ‘my Mum and Dad, children of the war’. Sadly they’re long gone, but I like to think they’d be pleased to be remembered. I have a feeling they would both enjoy reading Susan’s tale, and I hope you will too.

WRITING CHALLENGE

Imagine you are a child living in war-torn Britain, and you’re worried about your mum’s state of mind. How would you go about cheering her up? What kinds of obstacles would you face? And just how far would you go to overcome them?

Watch Tony's YouTube video about Operation Banana by clicking here.

Tony Bradman has been involved in the world of children’s books since the Jurassic Age (according to his grandchildren), although he maintains it’s ‘only’ since the 1980s. He has written for all ages, and is best known currently for historical fiction - books such as Viking Boy and Anglo-Saxon Boy (both Walker Books) and Queen of Darkness (Bloomsbury Educational) are very popular in schools. His books have been shortlisted for prizes many times, and he has won the Historical Association Young Quills Award twice, for Anglo-Saxon Boy, and also for Titanic: Death in the Water (Bloomsbury Educational), which he co-wrote with his son Tom.

Tony is also the consultant editor on the highly successful 'Voices' series of diverse middle-grade historical novels published by Scholastic, featuring books by writers such as Bali Rai, Patrice Lawrence, Kereen Getten and Benjamin Zephaniah.

Instagram - tony.bradman

Saturday, 4 March 2023

Clean Water for London? by Jeannie Waudby

John Snow suspected that dirty water was the problem. In 1849 he wrote a paper querying whether water could be transmitting cholera, but he faced a lot of opposition. Many people, even officials, were convinced of the bad air theory. Others were keen to blame cholera on poor people. It wasn’t until 1854 that John Snow was able to prove his water theory. He followed the trail of people who fell ill with cholera, and discovered that the first person to catch it was a woman who had fetched water from a pump contaminated by cholera-infected nappies. It was only in the mid 19th century that germ theory came to be understood so that helps explain why people resisted this for so long.Other diseases could be spread in water – for instance the deadly outbreak of typhoid that came from a poo in a well.

Many people got their water from stand pumps, wells or rivers but as the 19th century progressed more and more Thames water was pumped into buildings.The problem was that as London rapidly expanded, the river was becoming more and more contaminated by sewage and industry. It even came to be known as ‘the big Stink’. Eventually the Thames was so dirty that the Chelsea pump could no longer be used and in 1838 a new one was built in Brentford – the Kew Bridge Waterworks where the museum now is. The water was lovely and clean here because it was still mostly countryside, and at first the river water was pumped directly as it was. This pump used steam and was enormous. It’s still in the main block now.Soon after building the Waterworks, it was decided that the river water should be cleaned up before pumping it to Londoners’ homes. So a system of filter beds and reservoirs was created around the site. By 1848 all waste had to be discharged into street sewers. Unfortunately, these emptied into the Thames and unfortunately, when it rains heavily this still happens today.It’s very interesting to see all the different pumps that have been rescued and restored at the museum. Pumping water went from wind power to steam to electricity. There is still a pump working away to supply water to Londoners but now it is underground. Almost certainly, some of the electricity will come from wind energy.Writing Challenge

Clean water is a necessity of life. We are mostly made of water and we call our earth ‘the blue planet’ because so much of its surface is water. Poets have always written special poems to things, people, ideas or places that they love. This kind of poem is an ‘ode’. Can you write an Ode to Water? First make a list of the things you love best about water. Each one can become a line of your poem.

Here is my list:

Pushing my hands through blue swimming pool water

Raindrops on cobwebs

Wet pavements

Ice-cold tap water in winter

Soft dark green pond waterJeannie Waudby is the author of YA thriller/love story One of Us. She has recently completed a YA novel set in Victorian times.

Friday, 13 January 2023

Catching the Post by Catherine Randall

One of the things I used to associate with those quiet days after Christmas was having to write thank you letters. Before computers and smart phones, it was the only way to thank all the relatives and friends that I didn’t actually see at Christmas for the presents they’d kindly given me. Making a quick phone call to thank them was not an acceptable option in my family! Anyway, I quite enjoyed writing letters, which I suppose is not surprising given that I am now a writer.

Of course, nowadays, most people will have expressed their thanks in an email or a text message. I wonder how many actual physical thank you letters are written and put in the post these days?

One of the fun things about writing historical fiction is getting to discover how people did ordinary things in the past. In both my novel, The White Phoenix, and the novel I am currently working on, set in Victorian London, I’ve had to work out how my characters would communicate with each other without being able to pick up a phone, or send a text message or email. It got me thinking about how communicating has changed over the past 500 years.

To find out more, I visited the Postal Museum in London (on a rather windy day!)

From my research for The White Phoenix, I knew that the Royal Mail already existed in 1666, and that the General Letter Office in central London had burned down during the Great Fire with the loss of a huge number of letters. It was called the Royal Mail because it used the distribution system already in place for royal and government documents. This system had been put in place originally by Henry VIII (who else? He always gets involved!) and then in 1635 King Charles I made it legal to use the royal post to send private letters. The General Post Office, the state postal system, was formally and legally established in 1660 with post offices throughout the country connected by regular routes. But, as I learnt at the Postal Museum, post in those days did not necessarily remain private. Staff at the General Letter Office would open letters to check that no one was plotting against the King or the government, so if you wanted to make sure your letter was truly private, you needed to find another way to send it.

Luckily, people could also send letters by the carriers who plied between towns, taking people and goods, or by giving it to a friend travelling to the right town, or – if you had money – you could use a private messenger. In The White Phoenix, letters are often sent by carrier.

When the Post Office was first established, the mail was distributed by post boys travelling on foot. But post boys were slow and sometimes unreliable, and – unluckily for them – they were also vulnerable to highwaymen and pressgangs trying to forcibly recruit men for the army and navy. In 1784 smart new mail coaches replaced the post boys along many major routes which really speeded up mail delivery.

The next great innovation came in 1840 with the introduction of the Penny Black, the world’s first postage stamp. Until then, the cost of sending a letter depended on the number of sheets of paper included and the distance the letter had travelled and it was the recipient of the letter who paid for its delivery. You could choose not to pay, but then you didn’t receive the letter. I will never forget a story I once heard about two old and poverty-stricken friends who sent each other a blank sheet of paper every 6 months– they never accepted the ‘letter’ so they couldn’t pass on any news, but at least they knew that they were both still alive!

However, it wasn’t until 15 years later that post boxes were introduced - before that you had to take your letter to the nearest post office. The first post boxes were green, not the red we are used to today.

I was very happy to discover that post boxes began to appear on the streets of London at around the time my new novel is set – it made it so much easier for my main character to sneak out and post a letter! In a nice literary link, the famous Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope is credited with introducing the post box when he worked for the Post Office. The first post boxes in the UK were in the Channel Islands.

Post boxes have changed in colour and size and design since the mid-nineteenth century, but they are still instantly recognisable, whatever their age. The post box where I live has been painted gold since 2012, in honour of Mo Farah’s gold medal at the 2012 Olympics.

We might marvel at how much slower Victorian communications were than ours are today, but in Victorian London, you could expect to receive 12 deliveries of post a day – that’s one an hour! – and it was possible to send a letter by post and receive an answer the same day. Imagine that happening nowadays!

Of course, the fascinating displays in the Postal Museum cover the story of the Post Office right up to the present day, including such things as the introduction of the postcode, and the role post boxes played in the Second World War. If my next historical novel is set in the twentieth century, I will certainly be paying another visit, so that I can add authentic historical detail to my story. After all, people will always need to communicate with one another, and there’s nothing like an unexpected letter or a mysterious parcel to move a plot along!

Watch Catherine's YouTube video on Catching the Post by clicking here

The White Phoenix by Catherine Randall is an historical novel for 9-12 year olds set in London, 1666. It was shortlisted for the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award 2021.

Published by the Book Guild, it is available from bookshops and online retailers.

For more information, go to Catherine’s website: www.catherinerandall.com

Thursday, 21 April 2022

Thomas Coram and The Foundling Hospital by Jeannie Waudby

April is Care Experienced History Month so I wanted to feature the Foundling Museum in London.

Foundling Museum

Although it isn’t the original building, it's built on the site of the original Hospital.

The story begins in the mid 18th century when a retired sea captain and shipbuilder, Thomas Coram, returned from America with his wife Eunice. He was shocked by the poverty he saw, and the dead and dying babies in London’s streets. It was a time of extreme prejudice against unmarried mothers and their babies. He lost his own mother when he was only 3, and was sent to sea at the age of 11, and maybe these early separations gave him the insight to care for other children who had been separated from their families.

He decided to try and do something. It wasn’t easy because of the stigma but after 17 years he found support from ‘21 ladies of distinction’ and in 1739 received a charter from George II to build the hospital. In doing this, he started the UK’s first children’s charity.

As soon as it opened, the Foundling Hospital was inundated with babies. Mothers would bring their baby, often leaving a token to identify them as the child’s mother in the hope that they could reunite in the future. Some of these tokens are on view at the Foundling Museum, and they are heart breaking to look at.

Some of the tokens in the Foundling Museum

Some of them are simple objects that have been altered to make them more distinctive.

A bent thimble

Others are valuable or even engraved and show that not all the babies were there because of poverty.

An engraved token for Stephen Large

Some are handmade with a huge amount of care.

A lovingly crafted heart-shaped token

Life changed completely for the babies who were taken into the Hospital. They were given new names and sent to foster mothers in the countryside for the first four or five years, and many of them got to experience family life and love. But then they had to return to the Hospital, living communally and wearing a uniform.

It must have felt like losing their mum all over

again. Many of the foster mothers wanted to keep the children they had looked

after, but this didn’t often happen. Life would have become very different, in

an institutional environment with boys and girls segregated. But the children

received good healthcare and food and an education.

They were taught to read

and there was a choir so they also had music in their lives. At 13 or 14, later

16, they would be apprenticed or sent into service – having received an

education that prepared them for hard work.

In the early days, the Foundling Hospital had a lottery for which babies would be accepted – mothers had to pick a white ball out of a bag to get their baby in. In 1756 because of the demand, they made admission open and babies could be left in a basket and a bell rung to alert staff. But this caused the mortality rate to go up from 45% to 81%. It also meant that middlemen could charge mothers money to take their baby to the Foundling Hospital, with many dying on the way.

London's Forgotten Children by Gillian Pugh and Coram Boy by Jamila Gavin

Jamila Gavin’s fascinating teen novel CORAM BOY deals with this situation, as well as painting a vivid picture of 18th century England and capturing the vulnerability of children in a time of poverty and slavery. LONDON’S FORGOTTEN CHILDREN by Gillian Pugh tells the story of Thomas Coram and is packed with photos tracing the Foundling Museum’s history. In 1801 they changed the rules – babies had to be illegitimate and mothers had to bring their baby themselves.

All the babies were baptised and given a new name. In spite of the tokens and later receipts mothers were given when they left their baby, not many children were able to return to their mothers.

This painting from 1858 by Elizabeth Brownlow, a self-taught artist, shows a mother coming back to reclaim her little girl. The man behind the desk is the painter’s father John Brownlow. He was himself raised in the Foundling Hospital and later worked his way up to become its governor. It's possible that the kind Mr Brownlow in Dicken’s OLIVER TWIST is based on him. The certificate proving that the mother and child belong together has fallen on the floor.

The hospital moved first to Redhill and then to Berkhamsted where the air was fresher, where it remained until 1955. In the Foundling Museum, you can listen to recordings of people talking about their experience of growing up there in the 20th century.

In the 1960s, people came to understand that an institutional childhood, whether it is in a children’s home or a boarding school, makes it very difficult to meet a child’s emotional needs and that most children thrive in a family instead.

Coram has evolved into a charity committed to improving the lives of the UK’s most vulnerable children and young people. You can find its website here

It is currently working on Voices Through Time: The Story of Care , which aims to digitise the records of Coram’s work so that the voices and stories of children looked after through the Foundling Hospital can be saved for generations. It will include registers, documents about the children, letters from mothers and the records of fabric tokens mothers left to connect them to their child. Coram hopes to have this archive online in 2023.

Writing challenge

We’ve seen some of the tokens mothers left with their babies, to represent their love and in the hope of connecting again one day. Centuries later, we can look at these heartbreaking little objects and in doing so, keep their memory and story alive.

For this week’s writing prompt, think of an object that you could give to someone as a keepsake, to remind them of you. It can be simple or precious, imaginary or real, manufactured or natural, but small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. Describe this object – its colour, shape, what it’s made of, where you got it or how you made it. What does it say about you? What makes it special?

Jeannie Waudby is the author of YA thriller/love story One of Us (Chicken House.) She is currently writing a YA novel set in Victorian times.

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE First, watch the Time Tunnellers video about the Viking Attack on the Holy Island of L...

-

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE First, watch the Time Tunnellers video about the Viking Attack on the Holy Island of L...

-

That the Paralympics rose out of such a dark place, from the ashes of the Second World War, wounded men and a fugitive from the Nazis, says ...

-

On Thursday July 4th, the U.K will go to the polls to vote in the General Election. Eligible voters will select from a list of candidates wh...