I live in Scotland. Every January, primary schools return

from their Christmas break and, for the next fortnight, focus on the Scots

language. They recite poetry in preparation for one of Scotland’s most iconic

festivals. No, it’s not a saint’s day. No, it’s not religious or seasonal in

nature. It is a day to celebrate an iconic poet – Scotland’s national bard,

Robert Burns.

Schools hold Burns-themed assemblies, households up and down

the country empty supermarket shelves of haggis, neeps (swedes) and tatties

(potatoes). The radio warbles with My love is like a red, red rose. Tartan

is everywhere. School lunch halls echo with head teachers reciting The

Address to the haggis.

Other than the ‘ploughman poet’ label, I was surprised how

little people knew of Robert Burns. As a writer of historical fiction, had a

hunch that a children’s novel about the poet could do well, particularly in the

schools’ market in Scotland. Time to do some Time tunnelling. What could I dig

up?

It’s true, Robert Burns spent much of his life farming. However,

he also worked as an Exciseman on the infamous Solway Coast where smuggling was

rife, due to its proximity to both England and the tax haven of the Isle of Man.

At first glance, the poet’s day job sounds almost boring – working for the tax

office doth not an adventure make! I wondered if he had ever been involved in

anything interesting.

And, oh my goodness, did I strike lucky!

A side note on a museum website briefly mentioned that Burns

was involved in the seizure of the Rosamund, a smuggling schooner which

had run aground near the coast.

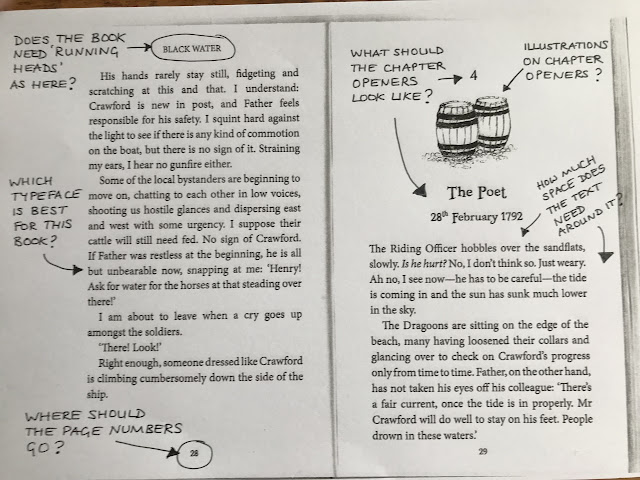

An extract about the seizure of the Rosamund

The ship was full of contraband which had to be

confiscated. The Exciseman in charge of the operation was one Walter Crawford,

an Excise riding officer whose job involved riding up and down the coast and

reporting any suspicious activity which may point to smuggling. The size of the

stranded ship meant he needed reinforcements, and fast. Over forty

horse-mounted soldiers marched into the freezing sea in three parties, led by

three Excise officers. Burns was one of them.

Because Crawford was relatively new in post, he kept a

meticulous diary of the operation: dates, times, people present and a blow-by-blow

account of what came to pass that February. To me as a writer of children’s

fiction, it was a kingly gift!

The Excise officers and the soldiers arrived on horseback

and attempted to ride into the sea. But the local beach was famously dangerous

for its quicksand.

Quicksand is very dangerous, and is found along the Solway coast

They had no option but to leave the horses behind and

proceeded on foot. According to Crawford’s diary, they waded into the wintry

waves in February 1792, while being shot at with the ship’s carronades (small

cannon) and with muskets. Despite the dangers they were under strict instructions:

to mount the ship ‘with pistol and sword’ and to seize the cargo, arresting the

dozen or so smugglers on board if possible.

They approached from angles on

which the ship’s cannon could not be brought to bear and eventually succeeded,

with the smugglers abandoning ship and fleeing across the narrow stretch of

water towards England.

Gosh, take a breath! What a story!

All I had to do was to throw a young apprentice Exciseman

into the mix – a children’s story needs a child protagonist. I didn’t have to

invent any of the jeopardy like I normally do – it was already there in real

life.

But it was also important to me to create a little balance – the

smugglers were not always the villains, of course – much of the smuggling took

place because of genuine need and poverty. I invented Old Finlay and his

granddaughter so that their perspective could also be included.

I pitched the book to my publishers. They loved the idea,

thankfully, but offered me some unexpected advice.

‘Barbara, schools only do this for a couple of weeks in

January. They start after Christmas and they finish on Burns Day, the 25th

of January. You need to give them something that they can read in that time.

Not a novel – a novella.’

Nothing for it. I cut my proposed manuscript by two thirds.

Barbara finishing her Black Water manuscript by the Solway Firth

The result is the smuggling novella Black Water. It’s

a story of sea and smuggling, of

quicksand, cannon fire, musketry and bravery, but of poetry too.

Anyone who thinks

that learning about Robert Burns is boring would be wise to take another look.

Extract from the Cranachan's (Barbara's publisher) catalogue