On Thursday 18th May 1536, a queen sat alone in a room in the Tower of London, waiting for her death.

Outside, on Tower Green, a scaffold stood draped in black, with wooden stands for the thousand spectators who would watch her execution the next day. A swordsman had been brought over specially from France: beheading by sword was quicker an cleaner than by axe. It was, in a way, an act of mercy.

The queen was Anne Boleyn, wife of King Henry VIII of England. She had been queen for about three years, and in that time had given birth to a girl who was to go on to become Queen Elizabeth I, one of the greatest rulers our country has ever known.

Anne had been crowned in triumph and splendour at Westminster Abbey, and had once been the subject of poems and love letters written by the king - so what had changed? What had brought her to that room, to that evening, to the sword that waited for her the following morning?

|

| Anne Boleyn (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) |

Guilty as charged?

Anne had been tried and sentenced to death for the crime of adultery: being unfaithful to her husband - and because her husband was the king, this made her guilty of treason. Five men - including her own brother, George - had already been executed for their part in her crimes.

But Anne's real crime was not adultery. Most historians now agree that the charges against her were false. So why had the charges been brought in the first place? What was Anne guilty of, that she had been arrested in the first place?

You could say she was 'guilty' of three things:

1. Not giving the king a son.

In Tudor England a king needed a son to rule after him - an heir - but King Henry VIII had no heir. His first wife, Katherine of Aragon, had given him a daughter called Mary, and Henry had eventually divorced Katherine and married Anne instead. Anne had also failed to give birth to a son, instead giving Henry another daughter, Elizabeth.

In Henry's eyes this meant that God was not pleased with him, and it gave him enough reason to start to look elsewhere for a wife, eventually settling on Jane Seymour, one of Anne's ladies-in-waiting.

|

| King Henry VIII (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) |

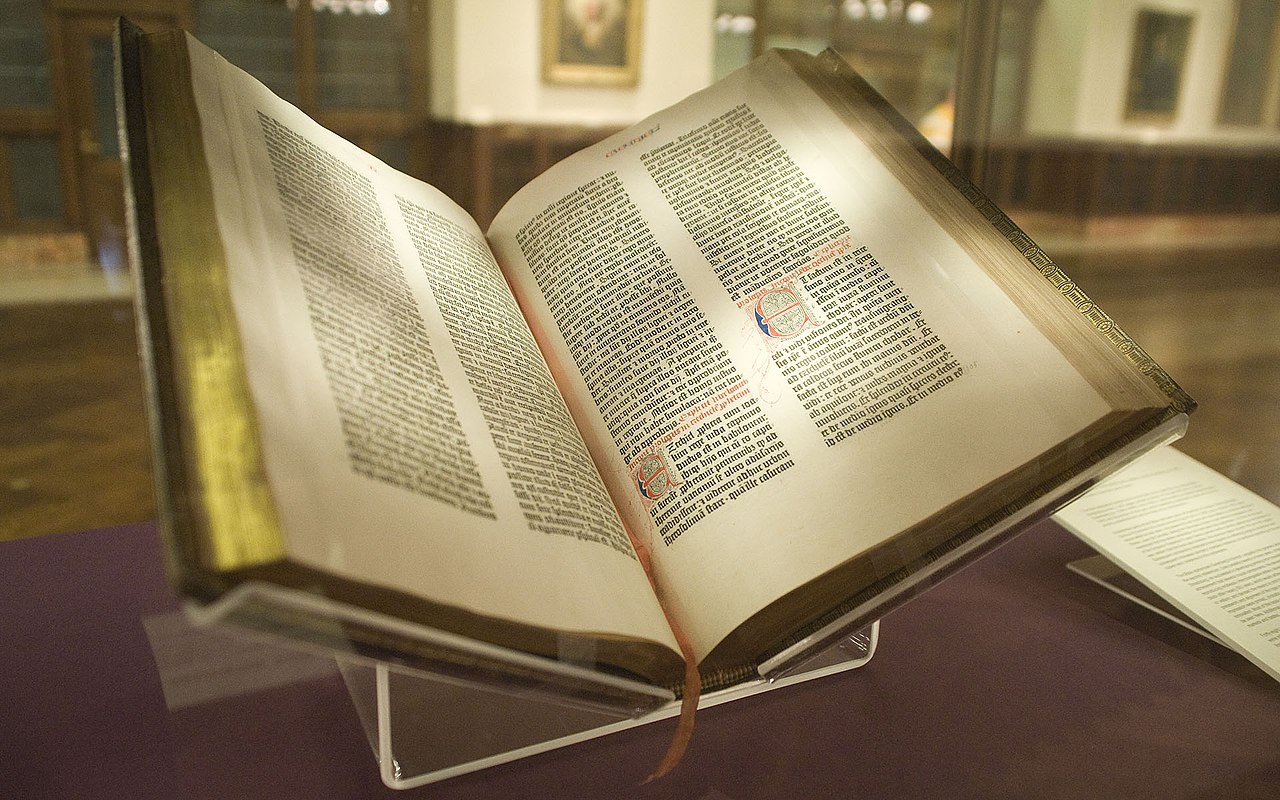

2. Supporting religious reform

Anne was very religious. At that time, the church was very powerful in England and all across Europe, but Anne disagreed with the power of the church. She, along with a growing number of people, believed that only the Bible could tell Christian people how to live - and that people should be able to read the Bible in their own language. Most Bibles were in Latin, and translating the Bible into English was counted as treason.

Supporting these changes in religion (called 'reformation') was dangerous for anyone - and maybe especially so for the wife of the king.

3. Making powerful enemies

This was perhaps Anne's greatest crime. She was a woman at a time when women were expected to be obedient to men, and worse than that she was outspoken and confident! She was not afraid to speak her mind, and frequently clashed with the men who advised the king.

One of her greatest rivals was a man named Thomas Cromwell, who had risen from humble beginnings to the role of the king's closest advisor. Historians believe it may have been Cromwell who arranged for the false charges to be brought against Anne, eventually leading to her death ...

|

| Thomas Cromwell (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) |

A timeline of death

2nd May - Anne is arrested for adultery and treason, and taken by barge to the Tower of London.

6th May - Anne writes a letter to King Henry VIII, begging his forgiveness for any offence she had caused but not admitting to adultery.

12th May - Four men are tried for adultery with Anne and found guilty.

15th May - Anne and her brother George are tried for adultery and treason and found guilty.

17th May - Henry's marriage to Anne is declared null and void - which means it is as good as if it never happened. The five men accused of adultery with Anne are beheaded.

18th May - Anne thinks that she is due to be executed on this day, but it is a mistake. Her execution is set for the day after. Her captors say that she is very calm and seems ready to die.

19th May - Early in the morning, Anne is taken to the scaffold on Tower Green. She is dressed very simply, and appears very calm. She gives a speech to the crowd who have gathered to witness her death (including Thomas Cromwell). She pays the executioner and forgives him (which was traditional). She is blindfolded, and kneels upright. The executioner swings his sword, and Anne passes into history.

|

| Anne Boleyn's Execution (Photo: Wikimedia Commons) |

Writing challenge

Anne was accused of crimes that she probably didn't commit. We all know what it's like to be accused of something we didn't do - how unfair it feels! But Anne was calm and graceful, and the letter she wrote to King Henry VIII was just as calm and graceful.

For your writing challenge this week, imagine you have been accused of something you didn't do. Maybe:

- Hitting someone else

- Breaking something

- Taking something that didn't belong to you

Write a letter to your accuser, explaining to them why you didn't do whatever it was. Be as persuasive and calm as you can. Don't accuse them of anything! Remember the idea is to convince them that you are innocent.

About the author

Matthew Wainwright is an author of historical fiction for young people. His latest book, 'Through Water and Fire' is set during the Tudor period and features an appearance by Anne Boleyn. It has been shortlisted for the Young Quills Award for historical fiction for young people, in the 11-13 age category.

_07.jpg)

_(14760920276).jpg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)