Throughout history there have been many dangerous books.

Sometimes books are labelled as ‘dangerous’ because they contain ideas that the authorities consider dangerous for people to read. Sometimes it's how people react to the books that is dangerous: people have been threatened, or even killed, because they had read, written or possessed some books. Sometimes the books really are dangerous, because the people who wrote them are trying to encourage people to hurt or attack others.

But why are books in particular objects of such contention? Why have people banned books, and why do they continue to ban books?

It's because books are vehicles for ideas—they’re one of the main ways that people express themselves to the world at large—and if humans are good at anything it’s getting upset at other people’s ideas!

The book we’re talking about today is perhaps one of the most contentious in the world. Certainly many people have died because of the things that it says, and because they have either supported it or disagreed with it. And yet it’s a book that many people in this country will have read, even if it’s just in part, and you’re probably never far from a copy.

The book is called The Bible, and it’s the book that most Christians use as their guide for life and faith. It can be called a ‘dangerous’ or ‘deadly’ book for two of the reasons listed above: various people throughout history have said that its ideas are dangerous; and people have sometimes reacted dangerously to those who read or possess it.

The Bible is a fantastic example of how people react to books, and it helps us to think about the power of books and reading. Let’s go down a Time Tunnel and find out a bit about one of the most influential (and dangerous!) books ever written …

The name ‘The Bible’ comes from a Greek phrase ‘ta biblia’, which simply means ‘the books’. It’s made up of several dozen parts, which were written and brought together over the course of about two thousand years. It includes Jewish religious writings, history, and poetry, as well as letters and accounts written by the followers of Jesus.

The first parts of the Bible (called the Old Testament) were written (for the most part) in ancient Hebrew. These parts were carefully handed down by the nation of Israel, and they were translated into Greek during the reign of Alexander the Great (about two or three hundred years before the birth of Jesus). Greek was the main language of the Middle East at the time, and people wanted to be able to read the Jewish holy texts in their own language.

After Jesus arrived, and founded what came to be called the Christian religion, his followers added their own writings (the New Testament) to the Jewish books, this time writing in Greek. By this time the Roman Empire had taken over most of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Romans spoke Latin, but most common people still spoke and wrote in Greek.

Over time, however, Latin took over as the main language of the Empire, and as Christianity grew and spread and became an important part of Roman society, the Bible was translated again—this time into Latin. Once again, people wanted to be able to read this important book in their own language.

Eventually Christianity grew into the dominant religion in Europe, and the Christian Church, led by the Pope, became a powerful religious and political entity. After the fall of the Roman Empire Latin faded away as the language of common people, replaced by the various languages and dialects of the new European kingdoms—including the kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons, ruled by Alfred the Great, in what we now call England.

At this point the Bible was still in Latin, and for the most part only those who were educated could read it. Various people, including King Alfred and a monk called Bede, translated parts of the Bible into the language of their people—but there was no complete Bible translation until the 1300s, when a man called John Wycliffe (with others) translated the Bible into English for the first time.

The Church of Rome was not happy about this, however, and in 1401 a law was passed that made Bible translation illegal. Many English Bibles were burned, and those who possessed them were arrested.

For over a hundred years there was no more Bible translation—until, in 1525, a man named William Tyndale printed a new English translation of the New Testament. At this point Bible translation was still illegal in England, however, so Tyndale had to work from Europe, in Antwerp.

Tyndale’s efforts were supported by the invention of the moveable type printing press some years before. Instead of having to hand-write each new copy, hundreds of copies of Tyndale’s translation could be printed at a time, meaning that his New Testament could be read by thousands of people very quickly, in their own language.

Tyndale’s supporters smuggled these printed copies of the New Testament into England, sometimes by hiding them in bales of hay. Those who did so literally risked their lives—the punishment for heresy and treason was execution by burning.

Religion in Europe was changing. Academics were beginning to question the absolute authority of the Roman Church, and King Henry VIII of England was beginning to wonder why he should have to obey the word of a Pope who lived in a city thousands of miles away.

Spurred on by his desire to get rid of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and marry the much younger Anne Boleyn, Henry broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and formed the Church of England, with himself as its head. Gradually, opposition to an English Bible faded, and the first official English Bibles began to appear in churches.

This came too late to save Tyndale, who was betrayed, arrested, and burned at the stake in 1536. Some historians also think that Anne Boleyn’s eventual arrest and execution was partly due to her over-enthusiastic support for those who wanted religious change—along with her failure to give Henry the son he so desperately wanted.

What followed was a time of immense upheaval. Allegiances and religious opinions changed sometimes overnight, and the wrong word could easily lead to arrest and execution. Many people suffered and died because of their beliefs at this time, on both sides of the argument. Some of the tensions continue to this day!

Now the Bible has been translated into nearly every language in the world, and there are numerous English translations to choose from. It is still a ‘dangerous’ book, and people still use it to justify doing terrible things to each other—but there are also many people who find its message life-changing, and who use its teachings to guide them into acts of kindness and charity.

All this helps us to understand the power of books. It’s amazing to think that paper and ink can hold such sway over the hearts and minds of people. But after all, it isn’t the paper or the ink that influences people, but the ideas they communicate.

No matter what you think of the Bible—or the Qur’an, or the Talmud, or the sacred texts of Hinduism or Buddhism or any other religion—they are remarkable objects, because they help us to travel through time and hear the thoughts and beliefs of people living thousands of years ago. Those people are long dead, but they still speak to us today through these books.

Sometimes books are labelled as ‘dangerous’ because they contain ideas that the authorities consider dangerous for people to read. Sometimes it's how people react to the books that is dangerous: people have been threatened, or even killed, because they had read, written or possessed some books. Sometimes the books really are dangerous, because the people who wrote them are trying to encourage people to hurt or attack others.

But why are books in particular objects of such contention? Why have people banned books, and why do they continue to ban books?

It's because books are vehicles for ideas—they’re one of the main ways that people express themselves to the world at large—and if humans are good at anything it’s getting upset at other people’s ideas!

The book we’re talking about today is perhaps one of the most contentious in the world. Certainly many people have died because of the things that it says, and because they have either supported it or disagreed with it. And yet it’s a book that many people in this country will have read, even if it’s just in part, and you’re probably never far from a copy.

|

| 'Tyndale's Bible' (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Bible is a fantastic example of how people react to books, and it helps us to think about the power of books and reading. Let’s go down a Time Tunnel and find out a bit about one of the most influential (and dangerous!) books ever written …

|

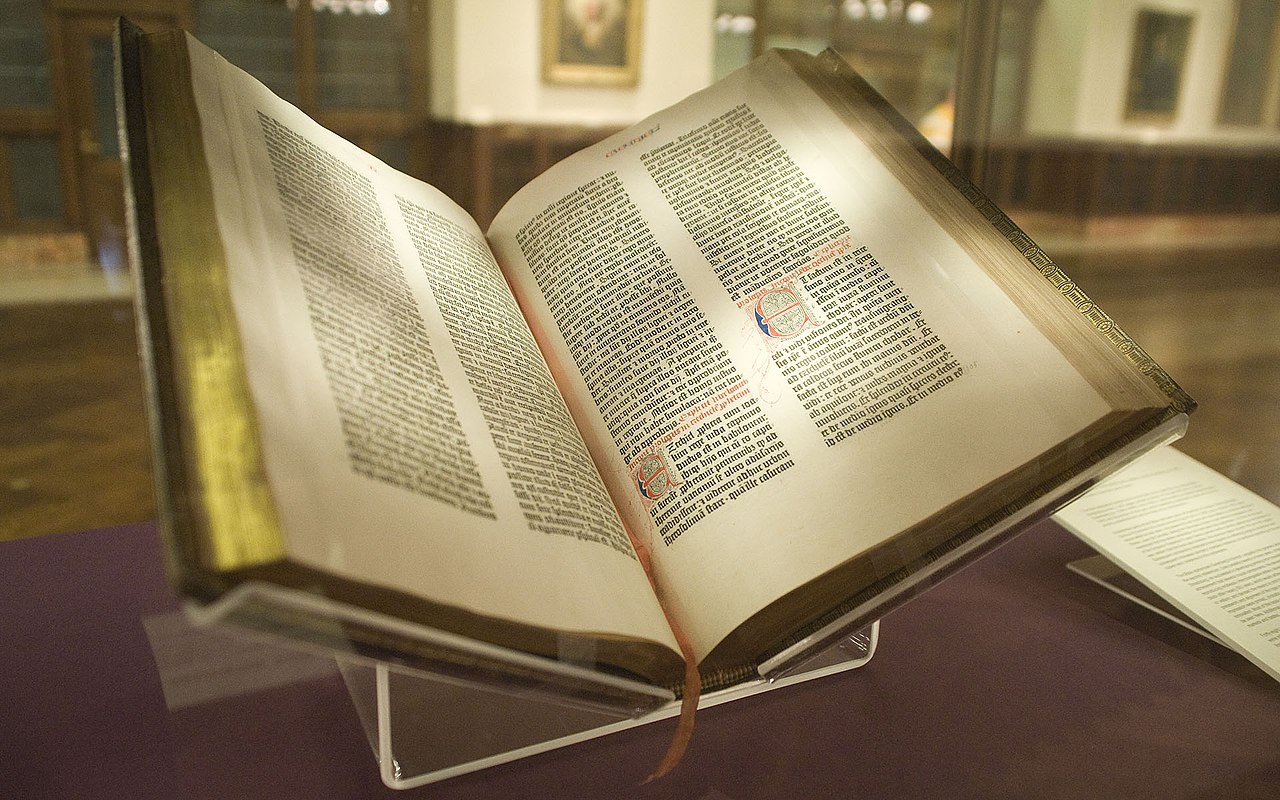

| 'Gutenberg Bible' (Wikimedia Commons) |

The name ‘The Bible’ comes from a Greek phrase ‘ta biblia’, which simply means ‘the books’. It’s made up of several dozen parts, which were written and brought together over the course of about two thousand years. It includes Jewish religious writings, history, and poetry, as well as letters and accounts written by the followers of Jesus.

The first parts of the Bible (called the Old Testament) were written (for the most part) in ancient Hebrew. These parts were carefully handed down by the nation of Israel, and they were translated into Greek during the reign of Alexander the Great (about two or three hundred years before the birth of Jesus). Greek was the main language of the Middle East at the time, and people wanted to be able to read the Jewish holy texts in their own language.

After Jesus arrived, and founded what came to be called the Christian religion, his followers added their own writings (the New Testament) to the Jewish books, this time writing in Greek. By this time the Roman Empire had taken over most of Europe, the Middle East and North Africa. The Romans spoke Latin, but most common people still spoke and wrote in Greek.

|

| Page of the Bible in Latin (Wikimedia Commons) |

Over time, however, Latin took over as the main language of the Empire, and as Christianity grew and spread and became an important part of Roman society, the Bible was translated again—this time into Latin. Once again, people wanted to be able to read this important book in their own language.

Eventually Christianity grew into the dominant religion in Europe, and the Christian Church, led by the Pope, became a powerful religious and political entity. After the fall of the Roman Empire Latin faded away as the language of common people, replaced by the various languages and dialects of the new European kingdoms—including the kingdom of the Anglo-Saxons, ruled by Alfred the Great, in what we now call England.

|

| Statue of Alfred the Great in Winchester (Wikimedia Commons) |

The Church of Rome was not happy about this, however, and in 1401 a law was passed that made Bible translation illegal. Many English Bibles were burned, and those who possessed them were arrested.

For over a hundred years there was no more Bible translation—until, in 1525, a man named William Tyndale printed a new English translation of the New Testament. At this point Bible translation was still illegal in England, however, so Tyndale had to work from Europe, in Antwerp.

.jpeg) |

| Reconstruction of an early moveable type printing press (Wikimedia Commons) |

Tyndale’s efforts were supported by the invention of the moveable type printing press some years before. Instead of having to hand-write each new copy, hundreds of copies of Tyndale’s translation could be printed at a time, meaning that his New Testament could be read by thousands of people very quickly, in their own language.

Tyndale’s supporters smuggled these printed copies of the New Testament into England, sometimes by hiding them in bales of hay. Those who did so literally risked their lives—the punishment for heresy and treason was execution by burning.

Religion in Europe was changing. Academics were beginning to question the absolute authority of the Roman Church, and King Henry VIII of England was beginning to wonder why he should have to obey the word of a Pope who lived in a city thousands of miles away.

|

| Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn (Wikimedia Commons) |

Spurred on by his desire to get rid of his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, and marry the much younger Anne Boleyn, Henry broke away from the Roman Catholic Church and formed the Church of England, with himself as its head. Gradually, opposition to an English Bible faded, and the first official English Bibles began to appear in churches.

This came too late to save Tyndale, who was betrayed, arrested, and burned at the stake in 1536. Some historians also think that Anne Boleyn’s eventual arrest and execution was partly due to her over-enthusiastic support for those who wanted religious change—along with her failure to give Henry the son he so desperately wanted.

.jpeg) |

| Statue of William Tyndale, Victoria Embankment Gardens, London (Wikimedia Commons) |

What followed was a time of immense upheaval. Allegiances and religious opinions changed sometimes overnight, and the wrong word could easily lead to arrest and execution. Many people suffered and died because of their beliefs at this time, on both sides of the argument. Some of the tensions continue to this day!

Now the Bible has been translated into nearly every language in the world, and there are numerous English translations to choose from. It is still a ‘dangerous’ book, and people still use it to justify doing terrible things to each other—but there are also many people who find its message life-changing, and who use its teachings to guide them into acts of kindness and charity.

All this helps us to understand the power of books. It’s amazing to think that paper and ink can hold such sway over the hearts and minds of people. But after all, it isn’t the paper or the ink that influences people, but the ideas they communicate.

No matter what you think of the Bible—or the Qur’an, or the Talmud, or the sacred texts of Hinduism or Buddhism or any other religion—they are remarkable objects, because they help us to travel through time and hear the thoughts and beliefs of people living thousands of years ago. Those people are long dead, but they still speak to us today through these books.

Whether it is a religious text, or an epic Greek poem, or a play by Shakespeare, or a novel by Dickens, or the latest bestseller that we read on a Kindle—books help us to communicate through time and space. They really are remarkable, and they should be treasured.

Writing challenge

For this week’s writing challenge we’re celebrating books! It’s a really simple challenge (hardly a challenge at all): just write a couple of lines about something you have read that you think everyone should read.

It could be a long book, a short book, a comic book, a poem, or anything else that you have read. Tell everyone why they should read it, and why it means so much to you.

That’s it! Happy reading and writing, and keep time tunnelling!

Writing challenge

For this week’s writing challenge we’re celebrating books! It’s a really simple challenge (hardly a challenge at all): just write a couple of lines about something you have read that you think everyone should read.

It could be a long book, a short book, a comic book, a poem, or anything else that you have read. Tell everyone why they should read it, and why it means so much to you.

That’s it! Happy reading and writing, and keep time tunnelling!

Matthew Wainwright is an author of historical fiction for children and teenagers.

You can preorder Through Water and Fire (released 31st October 2023) here. (Free UK postage on all preorders)

Out of the Smoke is available at all good bookshops and online.

You can find out more about Matthew and his books on his website.