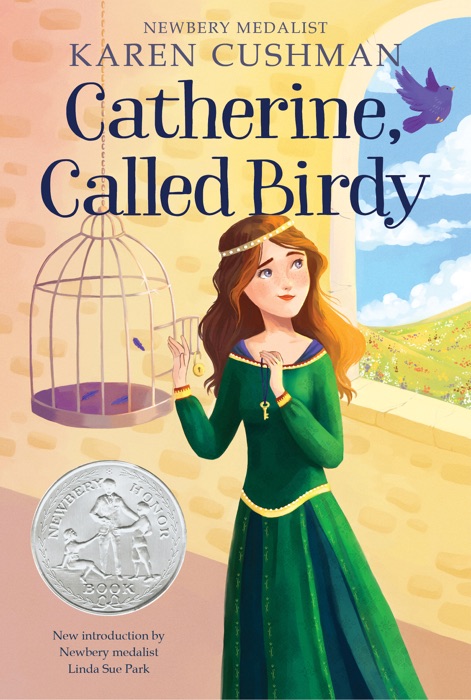

The inspiration for this blog post came from watching the recent film adaptation of Catherine, Called Birdy, American author Karen Cushman’s brilliant coming-of-age novel for young people set in 13th century England.

While I enjoyed the film, the book is even better. Through a series of short, and often laugh-out-loud diary entries, rebellious nobleman’s daughter, fourteen-year-old Catherine, nicknamed ‘Birdy’, recounts her determined efforts to stop her father from marrying her off to a series of unsuitable suitors while at the same time doing her best to resist the attempts of her mother and beloved nurse, Morwenna, to teach her how to be a lady.

Aside from Birdy’s voice and the cast of wonderful characters, from best friend and local goat-herd, Perkin, to the detestable ‘Shaggy Beard’, her future bridegroom, the other thing I love about the book is the brilliant recreation of the medieval world and in particular the banquets and entertainments which Birdy describes.

So, as Christmas is just around the corner, I thought it might be a good opportunity to get those tastebuds tingling by taking a closer look at what went into putting on a feast around the time Birdy’s story is set.

If you are to negotiate your way around a medieval banquet, it’s important to understand that society back then was hierarchical and divided into three broad social classes: the commoners or working classes, the clergy (priests, monks, nuns etc) and the nobility with the King or Queen and their family at the top. Food, like a person’s dress, was an important marker of social status. It was believed that while those working in the fields needed more basic types of food to suit their ‘rougher’ lives and work, the nobility should dine on more refined fare, better suited to their more discriminating digestive systems.

Banquets were a symbol of the nobility’s power as displayed through both their table manners and the meals they ate. But there was much more that went into the staging of a grand feast than the food. For a start, there was the dressing of the hall to be considered. For this, trestle tables would be brought in and covered with tablecloths, while a dresser would be set with drinking vessels, bread boards and serving tools. If guests were expected, then there would also be displays of plate – dishes and other serving vessels made of gold and pewter – all polished to a sparkle to impress.

Everyone attending the banquet had to wash their hands before taking their seats according to their status and position in the household. The lord, lady and their most important guests always sat at the top table, with the youngest, most junior members of the household sitting the furthest from them.

Once seated, everyone said grace. They were then handed trenchers cut from stale bread, or sometimes wood or pewter. These acted as plates into which the food was spooned from sharing bowls and platters handed round by attendants. Before the meal could begin, everyone had to wait for the lord to take a pinch of salt from the ceremonial salt cellar. On the occasion of a grand feast, every dish the lord was served was examined and tasted by a servant to make sure it hadn’t been laced with poison by one of his enemies.

There were no forks at table – these didn’t start to come into use until the very end of the Middle Ages. And diners had to remember to bring their own knives.

For a meal on an ordinary day, the lord might be presented with a choice of six dishes for the first course, though it could be many more at a grand banquet. If you were further down the pecking order, you would choose from just a couple. A second course and the sweetmeats and desserts that followed were offered only to those of the higher ranks.

Ale, perhaps mixed with herbs or else honey and spices, and watered-down wine were served to everyone at table. Though again, only those at the top table could choose how much water to take with their wine.

A stand-out feature of any grand medieval feast table was a ‘subtlety’, a sort of impressive decoration made out of sculpted sugar or else pastry. This was paraded around the hall before being presented to the lord at the top table. The grandest were often several tiers high and might include plaster figures depicting scenes from well-known tales.

Another important feature were the entertainments. Sometimes short plays or ‘interludes’ were performed by players between courses. Or there might be a longer play staged at the end of the meal including performances by musicians, tumblers and a type of costumed actor called a ‘mummer’. A talking point was the inclusion of ‘disguisers’ – people from the lord’s household dressed in masked costumes who might join in the dancing or else act something on their own before disappearing to leave everyone to guess the character they were playing and their true identity.

And now, at last to the food! We’re lucky that some of the old medieval recipes have survived. Here’s a flavour of some of the dishes you might have enjoyed if you had attended a banquet at that time.

Aside from baked goods like bread and rolls, there were vegetable dishes such as braised spring greens seasoned with nutmeg and cinnamon, leeks and onions cooked with saffron, and pottage, a sort of puree made of vegetables such as peas, carrots, leeks, beans and cabbage. Fish dishes included roast salmon in a wine sauce and Pike in Galentine – another type of spice-infused sauce.

Meat dishes might include boiled venison with pepper sauce, spit-roasted pork with spiced wine and, at Christmas, something called a ‘grete pye’ – a pie stuffed with two or three different types of meat (chicken, pigeon or wild duck and saddle of hare or rabbit) plus minced beef mixed with eggs, spices and dried fruit. And for those with a sweet tooth – but only if you were high-ranking remember! – rose-petal pudding, fig and raisin cream, or pine-nut candy.

Anything you couldn’t quite finish would be put in baskets on the tables and taken out after by the lord’s servants to distribute to local workers and beggars at his gates – a feast indeed for those who were used to much humbler ingredients or, worse still, very little at all.

And if you were suffering from an upset stomach caused by too much ‘pye’ the day after, or perhaps a headache from a surfeit of ale, there was usually a Wise Woman or an apothecary on hand with a recipe of their own to set you straight. A bad case of the colic? Then stuff your tummy button with a mixture of rancid butter and chopped saffron covered with a poultice of ale mixed with roasted earth for a sure cure!(?) Though probably best not tried at home!

Happy feasting! Oh, and watch out for those poisoners ...

Watch Ally’s video on medieval banqueting here

Ally Sherrick is the award-winning author of stories full of history, mystery and adventure. Black Powder, her debut novel about a boy caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, won the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award. Other titles include The Buried Crown, a wartime tale with a whiff of Anglo-Saxon myth and magic, and The Queen’s Fool, a story of treachery and treason set at the court of King Henry VIII. Ally's latest book, publishing February 2023, is Vita and the Gladiator, the story of a young girl's fight for justice in the high-stakes world of London's gladiatorial arena. She is published by Chicken House Books and her books are widely available in bookshops and online.

You can find out more about Ally and her books at www.allysherrick.com and follow her on Twitter: @ally_sherrick

No comments:

Post a Comment