Susan Brownrigg is the author of Kintana and the Captain's Curse, and the Gracie Fairshaw mystery series. (Uclan Publishing)

Find out more at susanbrownrigg.com

Susan Brownrigg is the author of Kintana and the Captain's Curse, and the Gracie Fairshaw mystery series. (Uclan Publishing)

Find out more at susanbrownrigg.com

Since my first published children’s book, Black Powder, I have always included an heroic – and sometimes downright mischievous – animal sidekick in my stories. In Black Powder, about two children caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, my hero Tom has a white pet mouse called Jago. Since then I’ve included a dog, a raven, a monkey and a wolf in other stories. And I’ve created two new animal heroes in my current historical work in progress, though I’m not quite ready to reveal their identities yet!

My own earliest memorable brush with an historic beast was a visit to the Natural History Museum in London and a meeting with Dippy the Diplodocus, who in the past few years has been making a grand tour of the UK and thrilling visitors young and old wherever he – or she? – lands. Dippy, as I later discovered, is a composite of many rather than one individual dinosaur’s bones, and also a cast taken from the ‘original’ Dippy housed in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, USA. But whatever its origins, it still has the power to excite young imaginations, as it did for me.

Other actual remains of creatures from the past which have intrigued and wowed me in equal measure over the years include the mummified cats on display in the Egyptian galleries at the British Museum, a plaster-cast taken from the remains of a dog caught in the ash flow of the devastating eruption of Vesuvius at Pompeii complete with its collar, and the skeletons of eleven horses buried with their presumed royal owner in a Viking-age ship burial at Ladby in Denmark in the early tenth century.

Medieval gargoyles on the outside of church towers and walls are also a favourite. I always look up before going inside to see if I can spot these strange, often nightmarish creatures created by medieval stonemasons, including this one of a devil or imp on St Peter’s Church in the Cotswolds town of Winchcombe. The word ‘gargoyle’ comes from the Old French word gargouille, meaning ‘throat’ and describes their practical function as waterspouts diverting rainwater from the roof. But historians believed they may also have served as charms to keep evil spirits away, or as a method of warning parishioners against committing sins.

And of course real and fantastical animals are often included in tapestries, on coats of arms and in sculptures and paintings too. For example I was lucky enough a little while ago to see the exquisite Hunt of the Unicorn tapestries in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

And on another holiday, this time to the city of Bangkok in Thailand, I visited the beautiful Buddhist temple of Wat Arun, home to many amazing sculptures including one of the deity Indra on his three-headed elephant.

Meanwhile, the image of a monkey in a painting of Katherine of Aragon, the first wife of the Tudor King Henry VIII, helped inspire the creation of Pepin the monkey in my own story The Queen’s Fool. I knew that monkeys in those times were kept as pets by the nobility in grand houses in England and Europe. But they would have seemed strange to ordinary folk, especially my hero, Cat Sparrow, who has grown up in the enclosed world of a nunnery. When she first encounters him, she mistakes Pepin – or Pippo as she prefers to call him – for some kind of giant spider. Understandable if you’ve never seen a monkey before!

Animals also make a frequent appearance on items of jewellery, clothing and even armour throughout history. While studying medieval history at university I learned about the Anglo-Saxon ship burial at Sutton Hoo in Suffolk. I was fascinated to discover that many of the treasures buried with King Raedwald whose monument it’s believed to be, depicted creatures both real and imaginary. I’ve talked in another TimeTunnellers post about the Anglo-Saxons’ passion for dragons, the most striking examples of which are on the warrior’s helmet included in the burial. But there were also stunning depictions of wolves and eagles – two of the so-called ‘beasts of battle’ – on other items including the king’s purse and shield mounts.

But perhaps my favourite representations of animals and birds in the past are in the illuminated manuscripts produced by monks in the scriptoria, or writing rooms, of medieval monasteries. The illustrations included in the copies of holy texts they made – including the beautiful early 15th century Sherborne Missal now in the British Library – were often both a celebration of the natural world and a very human testament to their vivid imaginations and colourful sense of humour. A form of escape perhaps from the bleak conditions they were working in sat at their desks in those cold and draughty monastery buildings.

Best of all, are the illuminated texts known as bestiaries. A bestiary was a compendium of beasts, with illustrations of animals and an accompanying description of their natural history and which usually included a moral message for the reader – mainly monks and clerics – drawn from the beast’s assigned religious meaning. They were first produced by ancient Greek scholars, but versions of them became increasingly popular during the Middle Ages, especially in England and France.

Bestiaries included both beasts that existed – for example pelicans, lions, bears and wild boars – and ones – spoiler alert! – such as griffins, unicorns, dragons and basilisks that didn’t. But no distinction about whether they were real or imagined was made in the entry.

There’s some debate among academics today about whether medieval people really believed the more fantastical ones actually existed or else accepted that they had been created for teaching purposes. But either way, many of these amazing beasts have found their way into fantasy stories and films of more modern times including works like Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings and J.K. Rowlings’ Harry Potter series and its spin-offs to name but a few.

Pick your own favourite real-life animal and taking inspiration from imaginary creatures in the past, with a wave of your pen transform it into a fantastical creature to include in your own 21st century bestiary. What sort of additional physical features will you give it to make it suitably weird and wonderful? Where does it live? What does it eat and drink? What sort of noise does it make when it’s happy, or angry? What special powers might it have? Write a few paragraphs describing it. And don’t forget to include a drawing of it too!

Ally Sherrick is the award-winning author of stories full of history, mystery and adventure.

BLACK POWDER, her debut novel about a boy caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, won the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award. Other titles include THE BURIED CROWN, a wartime tale with a whiff of Anglo-Saxon myth and magic and THE QUEEN’S FOOL, a story of treachery and treason set at the court of King Henry VIII. Ally’s latest book with Chicken House Books, is VITA AND THE GLADIATOR, the story of a young girl’s fight for justice in the high-stakes world of London’s gladiatorial arena.

Meccano, Hornby Trains, Dinky Toys – these beloved classic toys were all the creation of one man – Frank Hornby!

There is a bit of mystery about when Frank was born, his

birth certificate says 15th May but the Hornby family bible records

the date as 2nd May! But it is known that he was born in Liverpool

in 1863.

Frank was the 7th of eight children and his family were working class. His father was a porter

at the docks, and Frank preferred to help him at work rather than go to school!

From a young age Frank knew he wanted to be an inventor, but

he had a few setbacks along the way. Frank though was heavily influenced by a self-help

book he was given as a young man written by Samuel Smiles by his mother, which

encouraged resilience.*

He knew to persist, and when he went on to have a family of

his own, he had a breakthrough.

Playing with his sons he came up with the idea of creating a construction kit using strips of copper which he drilled holes into at regular intervals. These strips could then be fastened together using nuts and bolts to become bridges, trucks or cranes!

Convinced that his idea would make a successful business.

With a loan of £5 (£1000 today) he patented his invention with the title Improvements

in Toys or Educational devices for Children and Young People! After a bit of a

false start and the support of his employer who became his partner, in 1902

Frank began to produce his Mechanics Made Easy construction kits. The sets had

16 parts and an instruction booklet for making 12 models and cost 7s 6s (£80

today). It was a hit – though the name was later changed to Meccano!

More components were made available and there were even

competitions for new design suggestions with big prize money up for grabs!

In 1908 Frank’s family moved to a house in Maghull very

close to the railway station. His house, The Hollies, was the first outside of London to be given a blue plaque by English Heritage.

In 1920 Frank started making clockwork toys (Hornby O Gauge). Originally these were in the form of construction kits too, but after five years all Hornby Trains came already fully assembled.

Frank realised it would be great fun for children if they

could create railway layouts – lifelike scenes, not just track. The first set

of ‘modelled miniatures’ were six tiny station worker figures, and the story

goes that when he showed them to his daughter-in-law she said ‘they are dinky

little things’ so they were renamed Dinky Toys!

Dinky Toys included people, signage and a host of vehicles.

Other transport produced were speedboats, aircraft and motor car kits.

Other, perhaps less known, Hornby toys that were produced were The Meccano Crystal Radio Receiving Set, Cassy dolls and doll houses and Kemex chemistry sets.

While Meccano was marketed as engineering for boys, other products were advertised to appeal for girls too. Examples include Bayko (seen below) Dinky Builder and Dolly Varden dolls houses and furniture.

Frank went on to become an MP but had to retire due to ill health. He died in 1936 and was buried in the family grave at St Andrew's Church, Maghull.

His toys have provided children with many, many happy hours playing and creating inventions of their own, just like Frank.

Writing Challenge: Can you write a story about a child toy inventor? What type of toy will the create and what will it do? It might even have magical properties!

* Interestingly this book was also lauded by William Lever (the

soap king who was the subject of another Time Tunneller blog and video)

With thanks to Tony Robertson, Frank Hornby Heritage Centre, Maghull, for filming/photography permission

Everyone knows about the Great Fire of London. When I go into Year 2 classes dressed as a bookseller from 1666, the children tend to know almost as much about it as I do, which says a lot about how well it is taught.

But when I wrote The White Phoenix, my novel for 9 to 12 year olds set in London 1666, I had to delve deeply into the history of the Great Fire of London and I found out lots of things that I hadn’t known before.

1. It wasn’t the first Great Fire of London

If you’d talked to a Londoner in 1665 about the ‘Great Fire of London’, they would probably have assumed you were talking about the Great Fire of July 1212 – also called the Great Fire of Southwark. As its name suggests, this began in Southwark, just across the river from the City of London, at the south end of London Bridge. The fire destroyed most of Borough High Street and then began to spread across London Bridge, which at that time was covered with wooden houses and shops. To make matters worse, the wind blew embers across the river igniting the northern end of the bridge. Hundreds of people became trapped on the bridge – some fleeing the fire from the south, and some coming across from the north to help fight the fire. There are no reliable contemporary reports of the number who died, but a later historian suggested it could have been as many as 3,000. That seems very high, but whatever the truth, it is clear that many more people lost their lives in the fire of 1212 than in the fire of 1666.

There was another big fire in 1633 which destroyed premises on the northern third of London Bridge. You can see from this painting of the Great Fire of 1666 that there are no buildings on the north (left) side of the bridge. This is because these buildings had not been rebuilt after 1633, which proved to be a very good thing in 1666, because it created a firebreak on the bridge, preventing the Great Fire of London spreading to the opposite bank of the Thames.

2. England was at war!

In 1666, England was at war with two countries – the Netherlands and France. This was the Second Anglo-Dutch war, begun in early 1665, mainly due to rivalry over overseas trade. The stakes were raised in February 1666 when the French joined in on the side of the Dutch.

The war was fought mainly at sea, but all through the hot, dry summer of 1666 there was a very real fear of invasion. When the fire broke out, many people believed it was an act of war by the French or the Dutch, and that they'd deliberately set fire to the city. It meant that among all the chaos of people trying to save their houses and their possessions, mobs were going round attacking anyone thought to be French or Dutch. It was a terrifying time to be a foreigner on the streets of London.

3. The Mayor’s Nightmare...

Obviously, the big question about the Great Fire of London is how a city which was used to fires and had lots of procedures in place to deal with them allowed a fire to spread so far and so fast that it practically destroyed the whole city?

We’re taught lots of reasons for this – a hot summer, the wooden buildings all crammed together, a strong wind – but in fact there is one person who deserves to be better known, for all the wrong reasons: Sir Thomas Bludworth, the Lord Mayor of London.

The most important thing about controlling fires is to contain them straightaway. Sir Thomas Bludworth soon arrived at the scene of the fire, but he refused to let the firefighters pull down the houses on either side of Farriner’s bakery without the permission of the owners, and he didn’t know where the owners were because most houses were rented. So he just blustered and said the fire wasn’t as bad as all that, or words to that effect, and went home to bed. By the time he returned in the morning, the fire was out of control.

Both contemporaries and later historians consider Bludworth’s failure to contain the fire a crucial factor in its unprecedented spread.

4. Fire engine falls in the Thames!

Believe it or not, an early type of fire engine already existed at the time of the Great Fire, and there were several in London. Of course they were nothing like our modern fire engines, being basically pumps mounted on carriages. Sadly they were too large and too heavy to be of much help, and one of them even fell in the Thames!

5. A Frenchman was hanged for starting the Great Fire

A young French watchmaker called Robert Hubert confessed to starting the Fire by throwing a fireball through the window of Thomas Farriner’s bakeshop on the night of 1st/2nd September. It had already been established by the authorities that the fire had been started accidentally, and not maliciously, but Hubert insisted that he had done it and was brought to trial. When questioned, his story kept changing, he seemed to have no motive, and then it emerged that he hadn’t even been in London at the time. Nevertheless, he insisted that he had done it, and he was hanged for it.

Even at the time, this was seen as a bizarre miscarriage of justice, but for Londoners it did have a significant upside. When it came to the question of deciding who should pay for the rebuilding of London, the judges ruled that as the Frenchman Hubert had hung for it, the fire had legally been caused by an ‘enemy’, and therefore owners, not tenants, should pay for the rebuilding. Excellent news for ordinary folk!

6. The rebuilding

Despite many eminent people having lots of great ideas about new designs for rebuilding the City after the Fire, it was pretty much built on the same lines as pre-Fire London with the addition of one or two new streets. In fact, the layouts of the streets and buildings in the City of London didn’t change much until after the Blitz in 1940 during World War II.

WRITING CHALLENGE

After the Great Fire of London, there were appeals to towns and villages throughout the whole country to raise money to help the homeless citizens of London.

Imagine you are responsible for telling people in another town what has happened in London and why the city needs help. Can you describe what has happened and persuade people to give money? Your letter can be quite short, but you need to get some crucial information in there so that people realise just how much of a calamity it is, and how much of the City has been destroyed.

Catherine Randall is the author of The White Phoenix , an historical novel for 9-12 year olds set in London, 1666. It was shortlisted for the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award 2021. Catherine is currently working on a children's novel set in Victorian London.

For more information, go to Catherine’s website: www.catherinerandall.com.

|

| 'Tyndale's Bible' (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

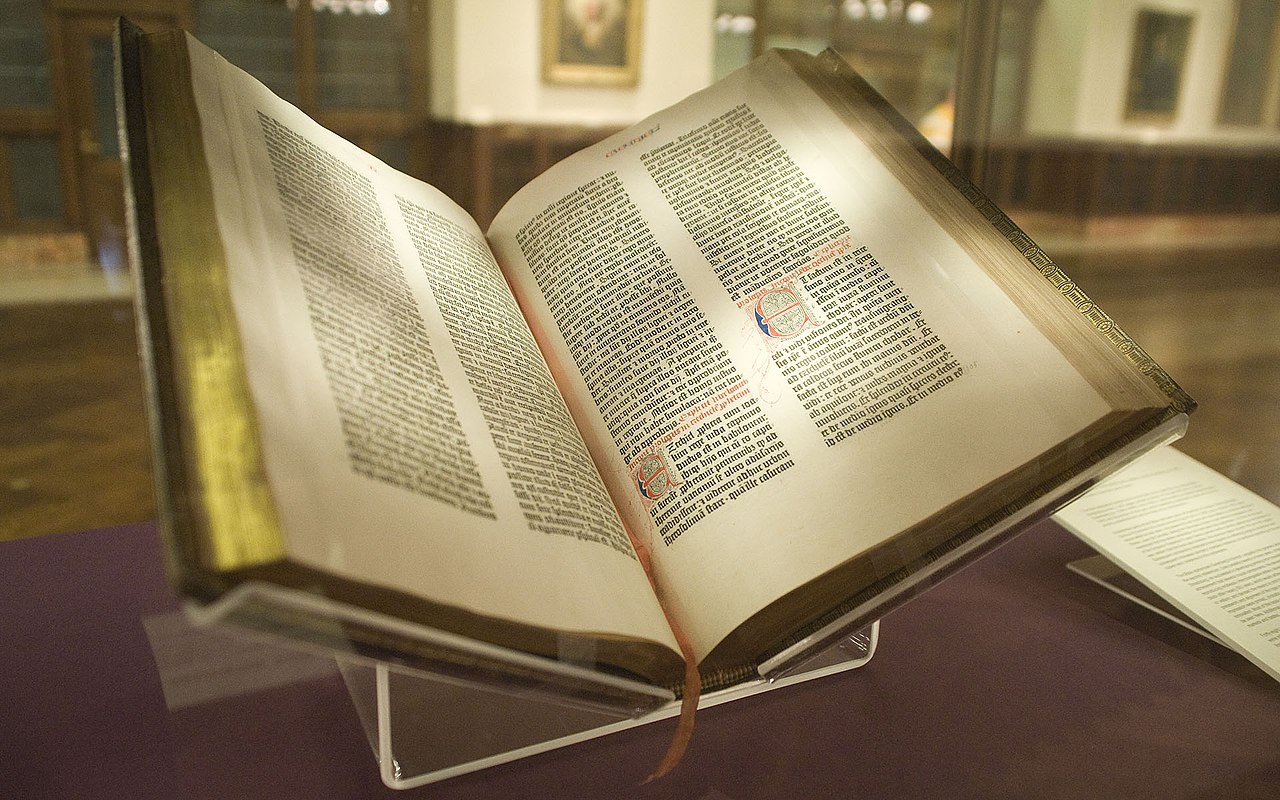

| 'Gutenberg Bible' (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

| Page of the Bible in Latin (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

| Statue of Alfred the Great in Winchester (Wikimedia Commons) |

.jpeg) |

| Reconstruction of an early moveable type printing press (Wikimedia Commons) |

|

| Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn (Wikimedia Commons) |

.jpeg) |

| Statue of William Tyndale, Victoria Embankment Gardens, London (Wikimedia Commons) |

Although Fablehouse is a book for 8 to 13-year-olds in the genre of magical adventure, with elements of Arthurian myth and legend, much of the story is based on a real place and a real period of social history that we haven't, traditionally, been told much about. One of my favourite things to do, creatively, is to incorporate history into the fiction I write.

Jasmine Richards (Storymix, who created the idea of Fablehouse) knew of my background when she considered me for the project. I grew up in care from the ages of 16 months until seventeen years old. I felt I had a lot in common with these children, even though I was born years later. For me, the most important aspects of a story are the characters and an emotional truth. I imagined that these brown babies would have grown up with a lack of identity, not knowing their fathers, and many probably experienced racism too. These were all aspects that I could identify with. These children had the stigma of being born illegitimate, as well as being mixed-race.

In 1941, the USA joined the Second World War because the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor. American GIs came over to Britain to help out, and between 1942 and 1946, millions of GIs passed through Britain. Around 240,000 of these were African-American. Troops were based all over, but perhaps part of why we don't know more about this history is because it's largely a rural one with many GIs stationed in the countryside in small towns and villages in the south and southwest of England.

With white local women and Black GIs meeting at dances and pubs, relationships were formed, and it's estimated that 2,000 'brown babies' were the result. (In the media these children became known as 'Britain's brown babies' - the term came from the American Press). At this time, Britain was a very white country, and the majority of the population weren't familiar with people from other countries; there was a lot of racism. Due to the US army not allowing the soldiers to marry their white girlfriends, it's estimated that perhaps 1,000 of these children were given up and not raised by their own parents. And of course, the reality is that some of these women - it's been estimated up to a third - were already married. The UK government opposed any adoption attempts by Americans, including the children's own fathers. The Mixed Museum (online at https://mixedmuseum.org.uk/brown-babies/) is an excellent place to start if you would like to know more about this topic.

My research came from Britain's Brown Babies written in 2019 by Professor Lucy Bland. Lucy's book tells individual stories set against historical context with discussions of the common attitudes of the day, and government policies and procedures.

Fablehouse - the actual house itself - is based on Holnicote House. From 1943, Holnicote House (a National Trust property) was used as a nursery for children who'd been evacuated from cities, and then later on, Somerset County Council used it to house the brown babies. In 1948, Somerset had around 45 brown babies and half of them were sent to Holnicote House. Children stayed there until they were around five years old when they'd then be sent elsewhere. In Lucy's book, she interviewed sixty children, five of whom used to live at Holnicote House. In reality, the house was for babies and toddlers, but obviously in my book, I've aged the children up - there wouldn't be much of an adventure if my main characters weren't able to be independent.

Now, Holnicote House is a hotel used by a company called HF who organise walking holidays. I went on a three-day trip to Selworthy in order to research the book. I wanted to walk the landscape of my characters.

WRITING CHALLENGE

1. Over the years, many of these brown babies tried to trace their fathers. As you can imagine, this is a highly emotional thing to do.

Write a conversation, or a monologue, imagining the moment where a child and a parent meet for the first time.

2. Think about someone you know and their personality traits. Now, imagine that one of those traits becomes developed to such an extent that it could become a superpower. What might that be?

E.L Norry (Emma) writes fiction and non-fiction for children. Her first book, a commission, Son of the Circus (Scholastic, 2019) is set in Victorian times with Pablo Fanque (the first black circus owner) as inspiration, and another historical book followed with My Story: Mary Prince (Scholastic, August 2022).

Emma likes to write different styles and genres. Amber Undercover, (OUP, 2021) is a fun action-adventure spy story for 10+. She also has short stories in: Happy Here (Knights Of, 2021), The Place for Me: Stories from the Windrush (Scholastic, 2020) and The Very Merry Murder Club (Farshore, 2021). Non-fiction includes a biography of Lionel Messi (Scholastic, 2020), and Nelson Mandela (Puffin, 2020) as well as work on Black in Time with Alison Hamond (Puffin, 2022) and Where Are You Really From? with Adam Rutherford, due out September 2023. April 2022 saw her first TV screen credit with an episode of Eastenders.

Fablehouse is a two book magical adventure series. Book 1 is out now (8 June, Bloomsbury) with Book 2 due April 2024. You can buy Fablehouse here.

You can find E.L. Norry on twitter at elnorry_writer or her website www.elnorry.com

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE First, watch the Time Tunnellers video about the Viking Attack on the Holy Island of L...