It was while researching my middle grade wartime story The Buried Crown, that I came across the discovery that at the height of invasion fever in 1940, the British Government had set in train plans to round-up so-called ‘enemy aliens’ and deport them to internment camps located both overseas in countries like Canada and Australia, or else in the British Isles.

One such ‘offshore’ location was the Isle of Man, situated in the Irish Sea midway between the northwest coast of the British mainland and Northern Ireland. But it was only on a recent holiday trip there that I discovered that the first instance of civilian ‘enemy alien’ detention on the island had actually occurred a quarter of a century earlier when it became home to the largest internment camp of the First World War.

The ‘enemy within’

In the run-up to the conflict, Britain was gripped by ‘spy fever’ and the belief that nationals from Germany and the Austro-Hungarian empire might be acting as enemy agents. When war broke out in August 1914, the Government passed the Aliens Restriction Act. This required men of ‘enemy’ nationality, including those who had lived in Britain for many years to register as ‘enemy aliens’. Their wives had to do so too, including those that were British-born, and who had effectively adopted their husband’s nationality on marriage. Failure to comply could result in a hefty fine or worse still, a period of six months in prison. The new rules allowed the Government to control the movement of those registered and to decide where they could live and what they could do.

Initially

the focus was on dealing with those who were believed to represent a potential danger

to the public. Camps for male internees were hastily set up in a variety of

places from old factories and workhouse buildings to trans-Atlantic liners off

the south coast of England, many totally unsuited to the new purpose they were

put to.

By the end of September 1914 a total of 10, 500 civilians had been interned. This included a number who were shipped across to the Isle of Man and housed in a former young men’s holiday camp in the capital, Douglas. But things speeded up in May 1915 after an outbreak of anti-German riots in Liverpool and London in response to the sinking of the Cunard liner, the RMS Lusitania by a German submarine with the loss over 1, 000 passengers and crew.

Now all non-naturalised

male civilians of military age – from 17 to 55 – were subject to internment,

whilst, wherever possible, all those too old for military service were to be sent back to their

country of origin. Women and children were also repatriated where the

authorities deemed it to be ‘suitable’. By November 1915 the number of ‘enemy

alien’ internees in the country had risen to nearly 32, 500.

An island prison

The Government

decided that the Isle of Man, located away from the mainland and surrounded by

water, would be a good place to detain a large number of these new internees. A

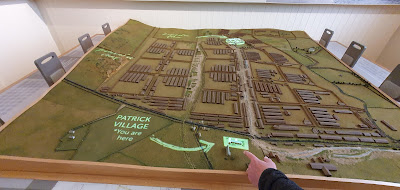

former army training camp at Knockaloe Moar Farm (pronounced Knock-ay-low) in the parish of Patrick

on the west side of the island had originally opened to take internees in the

autumn of 1914. Work now began to expand the site so that it could house a

significant majority of all civilian ‘enemy aliens’ from across the UK.

The camp was served by a specially built railway track connecting it to the nearby town of Peel. Building materials were brought in, and with internee labour working on its construction, it quickly grew to become the size of a small town, covering an area three miles in circumference and surrounded by nearly 700 miles of barbed wire. There were 23 hut compounds, each designed to take up to a thousand detainees. They were housed in five sleeping huts per compound, each one with a kitchen, recreation room, bath house, toilets, and also access to the camp’s hospital facilities.

It’s estimated that between November 1914 and when it finally closed a year after the war had ended in October 1919, the Knockaloe Internment Camp, with a capacity of 23, 000, had accommodated a total of some 30, 000 German, Austro-Hungarian and Turkish men plus around 4, 000 guards and civilian workers.

Life as an internee

Life inside the camp was basic and governed by daily rituals including an early rise at 6.30am, breakfast, a main midday meal and tea, two roll-calls plus hut inspections and lights-out. Internees with money were able to buy a range of goods and food from the local ‘dry canteen’, though alcohol was strictly forbidden.

They were permitted limited contact with the outside world and were entitled to receive two family visits a month. In reality, the cost and difficulty for the wives and children of ‘enemy aliens’ to visit them in a far-flung location like the Isle of Man meant that few did. However the men were also allowed to write short letters to their relatives twice a week and to receive letters and parcels in return. Both incoming and outgoing post was censored with censors on the look-out for the use of invisible ink and secret codes. Packages were also searched in case items such as home-baked cakes contained secret messages.

There were a number of escape attempts, particularly in the early days of the camp, with various tunnels discovered. But although some of the escapees came close, none were successful in leaving the island.

A more

serious problem in the camp was boredom. This, plus limited contact with family

and friends, the lack of privacy and not knowing when they might be released

resulted in a number of the men suffering from a condition known as ‘Barbed

Wire Disease’. Symptoms included melancholy, confusion, clouded thoughts and

amnesia and in some cases, ‘an aimless

promenading up and down the barbed wire boundary of the compound, like a wild

animal in a cage’ as one contemporary witness described it.

The best cure was found to be providing the internees with a purpose in life through work. The Friends’ Emergency Committee (a Quaker organisation) provided books, tools, equipment and materials so that internees could do woodwork and other crafts. The men were allowed to sell the goods they made via a number of approved routes to provide income for themselves and their families. Other work undertaken by internees included tailoring, boot-making, pipe-making, basket-making, building work and quarrying. Towards the end of the war, as the German army retreated from France, men at Knockaloe were even employed to make ‘flat-pack’ furniture for French families made homeless by the war.

There

was limited material available for many of these activities, but the internees

proved their inventiveness and resourcefulness by recycling waste material. For

example they turned old bully-beef tins into mugs, candlesticks and baking

equipment and left-over animal bones into trinkets and ornaments including

vases, napkin-rings and jewellery.

Other activities included art, music, putting on shows and a whole host of sporting activities from football, boxing and wrestling, to gymnastics, skittles and tennis. The camp also had its own printing press which produced a monthly newsletter – the Knockaloe Camp Gazette – along with Christmas and Easter cards, posters and theatre programmes. Or if none of this appealed, you could always tend to the camp flowerbeds and allotment plots.

And over

time members of the internee community set up a host of different schools in the camp providing

lessons in arithmetic, languages, shorthand and book-keeping, and more

specialist subjects such as electro-mechanics and agriculture.

Inspirational stories

The

internees were drawn from across the UK and a variety of different occupations

and backgrounds which straddled the classes. There were chefs, musicians,

hairdressers, waiters, businessmen, merchant seamen, cabinet-makers, teachers,

artists and interpreters among others.

Some

notable inmates included:

Theodore Kroell, the German-born manager of the

celebrated Ritz Hotel in London. He turned his hand and expertise to managing

the catering for several thousand prisoners in one of Knockaloe’s compounds and

was also involved in the camp hotel school giving lectures to large audiences.

Cecil Kny, an engineer and aircraft

designer before the war, went on to licence the Battery Electric Vehicle after

his release, a new type of motor vehicle designed to reduce Britain’s reliance

on imported oil.

Joseph Pilates, German-born boxer and circus-performer spent three and a half years of the war interned at Knockaloe. During this time Pilates was inspired to begin developing the theory and practice which became the basis of the now well-known exercise system of Pilates by observing the stretching techniques of the famous tailless Manx cats that lived on the island.

A bittersweet freedom

When the

war ended in November 1918, there were nearly 16, 000 men in the camp but it wasn’t

until a whole year later that the final one hundred or so left. In what seems a

terribly callous act now, most internees were deported back to Germany, many of

them having to leave their British-born wives and family behind. The women who

did accompany their husbands were often then subjected to anti-British feeling

having had to endure anti-German feeling during the war in Britain.

The camp itself was pulled down after the war and the site is now given over to green fields which play host to the annual Isle of Man Royal Agricultural Show. But the stories of some of the many men interned there so far from their homes and families, are told through the fascinating collection of objects, paintings and writings lovingly preserved in a small museum and visitor centre in the old Patrick village schoolroom just across the road. A testament to significant individual suffering, but also to the men's shared camaraderie, resilience and fortitude in the face of great isolation and hardship ...

Writing challenge

Imagine

you are arrested and taken far away from home, deported to a camp for ‘enemy

aliens’ such as the one at Knockaloe. Write a letter to your family describing

your first impressions of the place. What’s your new accommodation like? What sort

of people are your fellow internees? What food are you given to eat? How are you

treated by the people guarding you? And what will you do to try and keep the

boredom at bay?

Do you

think you might try and escape? If so, how? (But best not to put that bit in

the letter as remember: the censors will be reading it!)

Ally Sherrick is the award-winning author of stories full of history, mystery and adventure.

BLACK POWDER, her debut novel about a boy

caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, won the

Historical Association’s Young Quills Award. Other titles include THE BURIED CROWN, a wartime tale with a

whiff of Anglo-Saxon myth and magic and THE

QUEEN’S FOOL, a story of treachery and treason set at the court of King Henry

VIII. Ally’s latest book, published with Chicken House Books, is VITA AND THE GLADIATOR, the story of a

young girl’s fight for justice in the high-stakes world of London’s

gladiatorial arena.

For

more information about Ally and her books visit www.allysherrick.com You can also follow her on Twitter

@ally_sherrick

No comments:

Post a Comment