Saturday, 11 February 2023

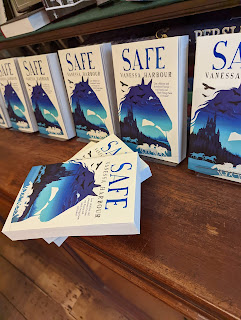

Children At War by Vanessa Harbour

The reason I am interested in the Second World War is because I was brought up on stories about it. My parents were teenagers at the beginning of the war. My father lied about his age so he could join up early. He drove tanks initially before becoming an officer in the Parachute Regiment.

My mother joined the WRNS and led quite a life, which she loved telling me about. The perception of children in the UK during the Second World War was that they were evacuated. And yes, over a million children were evacuated with their schools from towns and cities to the safety of the countryside. Most went by train and were settled with foster parents. For some who’d never been outside their cities it was an adventure; for others they were desperately homesick. It was hard to adjust to being separated from family and friends. One of my favourite books about evacuees is Good Night Mister Tom by Michelle Magorian.

However, for those who stayed in the cities things might have been very different. During the Battle of Britain, they might have watched the planes of the RAF and Luftwaffe in dog fights above them. During the Blitz itself, 7,736 children were killed and 7,622 were seriously wounded. The Blitz meant many children were orphaned or a sibling might have been killed during the bombing.

Their education was also disrupted as schools were damaged. Often, they might have to leave their classrooms when there were air raids. Many children pulled their weight. During the war, children left school at the age of fourteen and would be in full-time work, maybe agriculture, offices or major industries. Those over sixteen, including Girl Guides and Scouts assisted with Air Raid Precautions during an air raid. They’d take messages, be fire watchers or work with the voluntary services. Boys received their call up papers at eighteen, and soon girls were also conscripted, so would receive call up papers too. Check out Phil Earle’s book, When the Sky Falls. It deals with a lot of the issues that children had to face.

It wasn’t just the teenagers; younger children did their bit too. They’d salvage scrap metal, paper, glass and waste food for recycling. Also ‘digging for victory’. They still got a chance to be children though. They might have homemade toys. Books and comics were very popular. Children would happily play on bombsites and sometimes go to the cinema.

Children in Britain at least did not have to face the threat of persecution – unlike those in Europe. In both my books, Flight and Safe, the main characters Jakob and Kizzy constantly face the threat of persecution as one is a Jew and the other has a Romani background. In Safe, I also introduced the idea of 'Lost Children’ or Found Children as I called them. These were children that moved around Europe in packs at the end of the Second World War having lost all their relatives so they only had each other. Can you imagine how resourceful they had to be to keep themselves safe and alive?

Nazis had a tendency to pick on children. They would target them for racial reasons, or because they looked disabled, or if they had a suspicion they were linked to political activities/the Resistance. 1.5 million Jewish children were murdered by the Nazis – thousands of Jewish children were saved by being hidden away. The Nazis also murdered tens of thousands of Romani children, and 5000-7000 physically and/or mentally disabled children were also murdered. The Nazis were very cruel - this was all driven by Hitler’s desire to have a ‘perfect race’.

This is a child’s shoe found at Auschwitz, displayed at Peace Museum, Caen, France.As well as the concentration camps, Nazis created ghettos. Within the ghettos, Nazis considered the younger children to be unproductive because they couldn’t work so were named ‘useless eaters.’ Children in ghettos often died of starvation, disease, lack of clothing and shelter. If you want to know more about this time, Morris Gleitzman’s Once and Ian Serraillier’s The Silver Sword are powerful books based on true stories.

Children didn’t accept their countries being invaded or their friends being humiliated. They stood up to the Nazis in their own way whether it was in France, Netherlands, Belgium, Poland, or Czechoslovakia. All over Europe children stood with their parents in the Resistance to fight the anti-Nazi cause. Some maybe wanted adventure, some were desperate.

The resistance might take a childish form such as burping in soldiers’ faces or singing patriotic songs. Sometimes they would co-ordinate coughing fits when they were supposed to be watching Nazi propaganda films.

Their innocence could be of benefit though. No one would question a little girl pushing her doll’s pram, not realizing there were books hidden inside, taken from school to stop them being burnt, or a message maybe, or even a gun. The children might be used to hide or escort a shot down pilot or escaped prisoners of war. The danger was constant. A sixteen-year-old girl, whose parents had died, successfully hid thirteen Jews in her house to keep them safe, while looking after her younger sister. Check out Tom Palmer’s book Resist which is based on Audrey Hepburn’s war time experiences, getting information and passing messages to the resistance, while living in the Netherlands.

I want to keep remembering how brave these children were and I know in many wars all over the world there are many children being equally as brave.

Bio

Vanessa Harbour is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at the University of Winchester. Previously she ran her own PR & Management consultancy. Also, she used to work as an editor and Academic and Business Consultant at the Golden Egg Academy, and now writes online courses. She’s written for The Bookseller on being a disabled author. Flight, Vanessa’s first novel, is a World War II middle-grade thriller selected for Empathy LabUK’s Read for Empathy Collection 2020. Safe is Jakob and Kizzy’s second adventure, set against the last days of the War, involving horses and this time some ‘lost children’.Social Media

Twitter @VanessaHarbour Facebook https://www.facebook.com/VanessaHarbourAuthor Instagram @nessharbour Tik Tok @nessharbour YouTube: Channel: Vanessa Harbour https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCMZcIV7Ql2bPE1YeZFRwAlw Bookseller: https://bookwagon.co.uk/

Wednesday, 1 February 2023

Girl power, gladiator-style by Ally Sherrick

One of my favourite movies of all time is Gladiator. The multi Oscar-winning film, directed by Ridley Scott, stars Russell Crowe as wronged army commander turned gladiator-slave, Maximus Decimus Meridius who – spoiler alert! – seeks vengeance for the murder of his wife and child by his bitter enemy and rival, Emperor-in-waiting, Commodus.

It features all the classic ingredients of a great ‘swords and sandals’ epic – bravery, heroism and self-sacrifice plus a liberal dose of blood, sweat and the brutality of gladiatorial combat.When I set out to write my latest book, Vita and the Gladiator a story of my own set in that world, I wanted to make it about a hero who, like Maximus Decimus, finds themselves pitched into the arena against their will and forced to use their wits and courage to fight back.

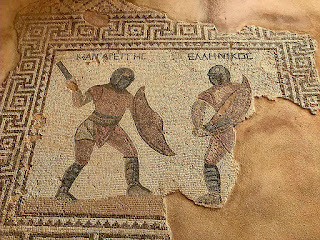

But while the film depicts a pretty much all-male world, the original inspiration for my story was sparked by a more unusual pair of gladiatorial fighters. These are Amazon and Achillia – two female gladiators (or gladiatrices as they are now known) whose memory is preserved in a stone relief from the ancient town of Halicarnassus (modern day Turkey) now housed in the British Museum.

Female gladiators were a rarity. In Roman society, women were expected to conform to the ideal of the Roman matron – to be decent, beautiful and devoted to their husband and family. The notion that they might want to fight in the arena was shocking. Nevertheless, there is both documentary and archaeological evidence – like the stone relief – that they did and that they drew the crowds too.

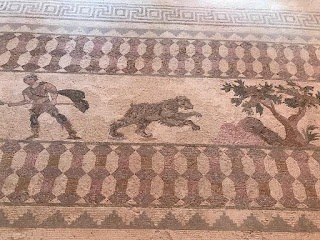

This discovery got my story whiskers twitching. Then, as I delved further into the world of the Roman arena, I discovered that women are recorded as having taken part in beast-hunts too. Known as venatores, beast-hunters were pitched against wild animals – both exotic ones like lions, tigers and even crocodiles – or, as was most likely the case in Roman Britain where my book is set, the more home-grown sort, like wild boar, bulls and bears.

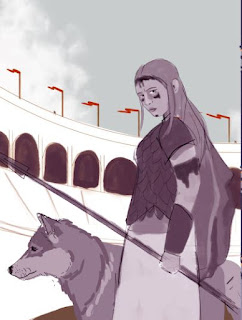

In truth, Brea, a native Briton, is a female beast-hunter (or venatrix) with her own dark back-story. At first Vita is terrified of the pair, but gradually, as she comes to trust Brea (known as Lupa or ‘the She-Wolf’ in the arena), she discovers they have a common enemy – one they must stand against together in the name of truth and justice.

The world of the gladiator is an alien one to us – barbaric and cruel-seeming. But at the time, the arena was the place where imperial justice was seen to be served and a sense of order reinforced – a reminder of the power of the Emperor in Rome and the meaning and worth of Roman citizenship. As such, it was a world with its own rules. But Vita has never been permitted to watch a gladiatorial games by her parents – women were in the minority in the audience as well as out in the ring. And one of the great things about writing the book was to have my hero – and the reader – discover these rules as the story unfolds.

For example Vita soon learns that most gladiators are either prisoners-of-war sold by their captors to fight in the arena, criminals sentenced to die by the sword or else condemned to the games, or slaves considered too unruly by their masters to keep. Though as she discovers, there are also the foolhardy types who volunteer for gladiator-school too.

Also that gladiators have to swear an oath – the sacramentum gladiatorum - agreeing to be ‘burnt by fire, bound in chains, beaten and killed by the sword’ as their master (the lanista) commands. And that fighters are only permitted to use wooden weapons during training for fear they might stage a revolt.

Vita – and Brea’s – survival depends on understanding how this strange and dangerous world works. But also on knowing when and how they can break the rules, as you’ll find if you read the book ...

Writing Challenge

Imagine that like Vita, you find yourself in a grand arena in front of crowds of baying spectators with little or no training. As you look around you, what do you see; hear; smell? Who is your opponent and how are they armed? What chance do you think you have of beating them and how does that make you feel? Die or survive to fight another day? It’s down to you!

Ally Sherrick is the award-winning author of stories full of history, mystery and adventure. You can find out more about her by visiting her website. Ally’s latest book, just published with Chicken House Books, is Vita and the Gladiator, the story of a young girl’s fight for justice in the high-stakes world of London’s gladiatorial arena.

Wednesday, 25 January 2023

The Windermere Children: The story of 300 child Holocaust survivors who came to the Lake District

In 1945 the people of Lakeland welcomed three hundred child Holocaust Survivors into their community.

A special exhibition at Windermere Library From Auschwitz to Ambleside highlights what life was like for these children. I visited to find out more.

Auschwitz to Ambleside exhibition

In 1942 the Nazis began what they called ‘the Final Solution’ - a plan to exterminate all Jewish people across Europe. Roma gypsies, gay and disabled people, as well as black and mixed-race people were also persecuted and killed.

It's estimated that eleven million people died in the

Holocaust including

By the

end of World War II, approximately 90 per cent of Europe’s Jewish children were

murdered in the Holocaust.

In June 1945, Leonard Montefiore, of the Central British Fund (now World Jewish Relief), persuaded the British Government to give permission for a thousand Jewish orphans aged from eight to sixteen to be brought to the UK for recuperation, and ultimate re-emigration overseas.

Just 732 actually came to Britain. They became known as The Boys, though they included 204 girls.

Of these, 300 children who had survived the Theresienstadt Ghetto in the Czech Republic were brought to Windermere. The youngest were just three years old.

Many of the children no longer knew how old they were and could not remember their date of birth, and lots were older than sixteen.

The Lake District Holocaust Project which curated the exhibition explains: “The Jewish children who came to the Lake District had been liberated in May 1945. Many had been used as slave labour in many camps across Nazi Occupied Europe for a number of years. The list of names of the camps they had experienced is an A-Z of horror. Auschwitz, Buchenwald, Majdanek, Warsaw ghetto, Lodz ghetto…..they each had a different story to tell of a different journey. Their discovery in Theresienstadt does not begin to cover their story.”

The children were to spend a period of recuperation in the Lakes before setting out on new lives.

The children were flown from Prague to Crosby on Eden airfield near Carlisle.

The Immigration Officer said: “The behaviour of the children was exceptionally good.”

From there the children were taken in a convoy of buses and army trucks to Calgarth - a wartime housing estate built to accommodate workers from the Short Sunderland Flying Boats factory on the shores of Windermere.

The single workers no longer needed the rooms at the now lost estate, near Troutbeck Bridge - and there was the perfect number available for each child to have their own private room.

Arriving in the Lake District was described by the children as like being in “Paradise”.

The Lake District Holocaust Project website explains: “The estate had its own shops, canteen, entertainment

hall and many other facilities. They were each given their own small

room, a bed and clean linen. For many it was their first encounter with privacy

and cleanliness in five years.

One quote on display is from Ben Helfgott, who was 15 when he came to Calgarth. “I'll never forget the smell of the fresh linen I slept on that first night ... I can't remember ever having a better night sleep ... It was only a hut, but to me it was a palace.”

The children became known as the Windermere Boys - although the group included 35 girls.

Most young survivors were male and the Nazis considered girls less useful for slave labour.

When they arrived they could not speak English, so they were given language lessons.

The children were offered opportunities for sport, education, outdoor recreation and healthcare.

Over a period of six months, they were

gradually moved to other homes in places throughout the UK, and they had left

Calgarth Estate by early 1946.

Around 30-40 children moved to Manchester, others to Liverpool, Gateshead and London. Some left Britain, to America, Canada and Israel.

Outside the library there is a memorial garden to the Windermere Children with colourful artwork and planting that tells the journey of the children through the language of flowers.

The interpretation explains: “Many of the children spoke of their love of the luscious green of the Lake District and described it as an explosion of colour after the horrors of the camps.”

Plants chosen include heather (protection) daffodils (new beginnings) and snowdrops (hope.)

The children's story is also retold in the BBC

film The Windermere Children and the accompanying documentary The Windermere Children: in their own words.

The book After the War : From Auschwitz to Ambleside by Tom Palmer tells the story of the Windermere Boys in a dyslexia friendly accessible format. It is published by Barrington Stoke. The Centre for Holocaust education offers lesson plans for schools studying the book.

The '45 Aid Society was set up in 1963 by some of the 732 children who came to Britain in 1945. Their children continue the society's work.

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust (HMDT) encourages remembrance in a world scarred by genocide. They promote and support Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) – the international day on 27 January to remember the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust, and the millions of people killed under Nazi Persecution and in genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur. 27 January marks the anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp.

Useful links:

https://www.hmd.org.uk/take-part-in-holocaust-memorial-day/schools/primary-schools/

https://holocausteducation.org.uk/lessons/open-access/lesson-materials-to-support-after-the-war-a/

Thursday, 19 January 2023

From Guan Yin to Xuanzang - a road trip through Chinese myth and history by Maisie Chan

By coincidence, Scholastic asked me if I wanted to write a story for Bedtime Stories: Amazing Asian Tales from the Past. They had a list of historical figures - I chose Xuanzang. He travelled from China to India because he wanted to translate and return to China with updated Buddhist scriptures. This is the real life person that Wu Cheng’en was inspired by when he began writing The Journey to the West! Xuanzang became a Buddhist monk before he was an adult. He followed in his brother’s footsteps. His life up to his teenage years were not easy. His parents had passed away, his country was experiencing civil war and he and his brother had to find refuge in a new city. When reading the Buddhist scriptures Xuanzang found they were incomplete or did not always make sense because of the poor translation. He decided that he wanted to go to India himself, learn Sanskrit and go on an adventure. However, Emperor Taizong forbade him from leaving. Xuanzang made the decision to sneak out because he felt it was his destiny. It was a big risk for him to go without the proper travel passes. He travelled the Silk Road with merchants. But he encountered quite a few obstacles. He was abandoned by the merchants, had to cross tough terrain and in one town, a King wanted to keep him there FOREVER. But Xuanzang had a mission, he needed to make it to India. He persuaded the king to let him go. After more treacherous travel he finally made it.

He did what he set out to do, he learned Sanskrit. And in AD 645 decided to head back to China with newly translated Buddhist scriptures. His writings were the foundation of Buddhism in China where it is one of the most popular religions.

When I wrote Keep Dancing, Lizzie Chu I was thinking about her road trip as an inner journey as well as an external one of getting to Blackpool to have some fun. I wondered how she and her friends would be changed by that trip? And who or what might stand in her way. I think of road trips in stories as a great way for the main characters to learn something about themselves, other people, and the world around them.

Writing exercise:

Think of a historical figure. Write a contemporary story about a road trip with this person and you, or a character you make up. Where would you take them? Who would you meet on the way? What would happen once you got there?

Maisie Chan is a children's author whose debut novel DANNY CHUNG DOES NOT DO MATHS won the Jhalak Prize and the Branford Boase Award in 2022. It was also shortlisted for the Blue Peter Book Awards and Diverse Book Awards 2022.

Her latest novel KEEP DANCING, LIZZIE CHU is out now with Piccadilly Press. She also writes the series TIGER WARRIOR for younger readers. She has written early readers for Hachette and Big Cat Collins, and has a collection of myths and legends out with Scholastic. She runs the Bubble Tea Writers Network to support and encourage writers of East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) descent in the U.K. She has a dog called Miko who has big eyes. She lives in Glasgow with her family.

You can buy Maisie's books here.

Friday, 13 January 2023

Catching the Post by Catherine Randall

One of the things I used to associate with those quiet days after Christmas was having to write thank you letters. Before computers and smart phones, it was the only way to thank all the relatives and friends that I didn’t actually see at Christmas for the presents they’d kindly given me. Making a quick phone call to thank them was not an acceptable option in my family! Anyway, I quite enjoyed writing letters, which I suppose is not surprising given that I am now a writer.

Of course, nowadays, most people will have expressed their thanks in an email or a text message. I wonder how many actual physical thank you letters are written and put in the post these days?

One of the fun things about writing historical fiction is getting to discover how people did ordinary things in the past. In both my novel, The White Phoenix, and the novel I am currently working on, set in Victorian London, I’ve had to work out how my characters would communicate with each other without being able to pick up a phone, or send a text message or email. It got me thinking about how communicating has changed over the past 500 years.

To find out more, I visited the Postal Museum in London (on a rather windy day!)

From my research for The White Phoenix, I knew that the Royal Mail already existed in 1666, and that the General Letter Office in central London had burned down during the Great Fire with the loss of a huge number of letters. It was called the Royal Mail because it used the distribution system already in place for royal and government documents. This system had been put in place originally by Henry VIII (who else? He always gets involved!) and then in 1635 King Charles I made it legal to use the royal post to send private letters. The General Post Office, the state postal system, was formally and legally established in 1660 with post offices throughout the country connected by regular routes. But, as I learnt at the Postal Museum, post in those days did not necessarily remain private. Staff at the General Letter Office would open letters to check that no one was plotting against the King or the government, so if you wanted to make sure your letter was truly private, you needed to find another way to send it.

Luckily, people could also send letters by the carriers who plied between towns, taking people and goods, or by giving it to a friend travelling to the right town, or – if you had money – you could use a private messenger. In The White Phoenix, letters are often sent by carrier.

When the Post Office was first established, the mail was distributed by post boys travelling on foot. But post boys were slow and sometimes unreliable, and – unluckily for them – they were also vulnerable to highwaymen and pressgangs trying to forcibly recruit men for the army and navy. In 1784 smart new mail coaches replaced the post boys along many major routes which really speeded up mail delivery.

The next great innovation came in 1840 with the introduction of the Penny Black, the world’s first postage stamp. Until then, the cost of sending a letter depended on the number of sheets of paper included and the distance the letter had travelled and it was the recipient of the letter who paid for its delivery. You could choose not to pay, but then you didn’t receive the letter. I will never forget a story I once heard about two old and poverty-stricken friends who sent each other a blank sheet of paper every 6 months– they never accepted the ‘letter’ so they couldn’t pass on any news, but at least they knew that they were both still alive!

However, it wasn’t until 15 years later that post boxes were introduced - before that you had to take your letter to the nearest post office. The first post boxes were green, not the red we are used to today.

I was very happy to discover that post boxes began to appear on the streets of London at around the time my new novel is set – it made it so much easier for my main character to sneak out and post a letter! In a nice literary link, the famous Victorian novelist Anthony Trollope is credited with introducing the post box when he worked for the Post Office. The first post boxes in the UK were in the Channel Islands.

Post boxes have changed in colour and size and design since the mid-nineteenth century, but they are still instantly recognisable, whatever their age. The post box where I live has been painted gold since 2012, in honour of Mo Farah’s gold medal at the 2012 Olympics.

We might marvel at how much slower Victorian communications were than ours are today, but in Victorian London, you could expect to receive 12 deliveries of post a day – that’s one an hour! – and it was possible to send a letter by post and receive an answer the same day. Imagine that happening nowadays!

Of course, the fascinating displays in the Postal Museum cover the story of the Post Office right up to the present day, including such things as the introduction of the postcode, and the role post boxes played in the Second World War. If my next historical novel is set in the twentieth century, I will certainly be paying another visit, so that I can add authentic historical detail to my story. After all, people will always need to communicate with one another, and there’s nothing like an unexpected letter or a mysterious parcel to move a plot along!

Watch Catherine's YouTube video on Catching the Post by clicking here

The White Phoenix by Catherine Randall is an historical novel for 9-12 year olds set in London, 1666. It was shortlisted for the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award 2021.

Published by the Book Guild, it is available from bookshops and online retailers.

For more information, go to Catherine’s website: www.catherinerandall.com

Tuesday, 6 December 2022

Christmas and Mary, Queen of Scots by Barbara Henderson

It is hard to imagine that not so very long ago, Christmas celebrations were frowned upon in this country. I share a December birthday with the famous Mary, Queen of Scots. Both of us were born on the 8th of December, in the run up to Christmas. You may not be aware, but Mary’s father died days after her birth in 1542. He had recently sustained a humiliating defeat at the Battle of Solway Moss. Bruised and ailing, he visited his pregnant wife at Linlithgow Palace before travelling on to Falkland Palace where he took to his bed with a fever. When he heard that his wife, the French-born Mary of Guise had given birth to a girl rather than the hoped-for male heir, it is said that he turned his face to the wall and died of despair!

Tuesday, 29 November 2022

Ferdinand Who? By Candy Gourlay. Illustrated by Tom Knight

I thought I’d use this opportunity to talk about Ferdinand.

Ferdinand who? You may ask. Ferdinand Magellan! I wrote a book about him, illustrated by Tom Knight who weirdly is in the same pose as me in these photos. Funnily enough, my book is part of a book series called First Names, which tries, through comics and stories, to make readers get to know notable people on a first names basis.

When my publisher asked me who I would like to write about, I proposed Ferdinand – Ferdinand Magellan, the explorer!

Where I grew up – in the Philippines – Ferdinand was famous for DISCOVERING the islands that became my native country! Discovering us whether we liked it or not, I always say – how would you feel if someone turned up at your house and told you he now owned it because he’d discovered it? But I am jumping ahead of myself.

Way back in 1519, Ferdinand set off with a fleet of ships from Spain, crossing the Atlantic Ocean to Brazil. He sailed down the coast of the continent we now know as Latin America, until he came to a gap.

Nobody had ever seen that gap before. He believed that he could make his way through the gap to the other side of the continent. Other explorers before Ferdinand had seen an ocean, on the far side of the continent. So he knew it was there.

And Ferdinand found the way through to it.

The passageway he found is now called the Strait of Magellan. And the ocean came to be called the Sea of Magellan. But today, we now know it as the Pacific Ocean.

Many terrible things happened to him on the way. In the 16th century, ships and navigation tools were primitive. They could only taste the water to figure out if they were on a fresh water river or on the right track on a salty ocean. They had no fridges to keep their food fresh, so they had to carry cattle and when that was gone, they had to hunt for food on the shore.

Worse still, his men hated him, probably because Ferdinand was a bit arrogant. He was also Portuguese while many of his men were Spanish – and the Spanish and Portuguese were deadly rivals. There were several nasty attempts by Spanish men to take control from Ferdinand. One of his ships even turned around and sailed back to Spain.

And by the time they reached the Pacific, they were all suffering from sickness and starvation.

And most shocking of all: Ferdinand didn’t have a map. He didn’t know where they were going.

Why would someone VOLUNTEER to go on such a terrible voyage?

Here’s why: Ketchup. French Fries. Pizza. Pasta. Curry. CHOCOLATE.

NONE OF THESE EXISTED IN EUROPE WHEN FERDINAND WAS A KID.

There were no tomatoes. No potatoes. No pasta. No coffee. No sugar. No Spices. No chocolate.

Can you even begin to imagine what life was like for without all these things?

Rich people could buy spices – which were used for everything from deodorant to improving the flavour of food. Remember, there were no fridges, so meat was always slightly off.

The spices came from far away lands, carried by Arab traders across the vast European and Asian continent.

But then the great Ottoman empire rose in the East. They blocked the trade with Europe and Europeans had to find another way to get their spices.

And then some ships began to improve. They could sail longer and longer distances.

Some men, who were a lot braver than they were clever, began to venture out to explore the world beyond Europe.

And when they came back, oh the stories they told! They brought gold and strange new food.

When young Ferdinand was growing up, explorers were like ROCK STARS. And he dreamed of becoming an explorer himself.

In my book I tell the story of how Ferdinand fought to become an explorer. His journey to the other side of the world was filled with adventure and peril. And he had some successes. He was the first European to sail the Pacific Ocean. There is a penguin named after him, the Magellanic Penguin. As well as two dwarf galaxies, now called the Magellanic Clouds.

Mind you, poor Ferdinand died before he ever knew that these things were named after him.

But the most important thing that Ferdinand was known for was being the first man to sail all the way around the globe. But that’s another story.

On his early travels, reaching as far as what we now know as Malaysia by rounding the southernmost point of Africa, Ferdinand had acquired a boy as his slave whom he named Enrique. We know about Enrique because Ferdinand mentions him in his will and later, a man named Antonio Pigafetta, who went on the voyage with Ferdinand, wrote about him. When at last Ferdinand crossed the Pacific Ocean and landed in a group of islands teeming with people – which we now know as the Philippines – he was astonished to find that Enrique could speak their language.

Pigafetta wrote down a list of words from the language and guess what, it’s the language that my parents speak, called Cebuano.

Because Enrique could talk so fluently, Ferdinand had no trouble being understood by the islanders – he even tried to convert them to his religion! After a long and terrible journey, Ferdinand felt successful at last. Maybe that’s why he offered to attack the enemy of one of the island kings. Which was a disaster.

Ferdinand was killed on the island of Mactan, in a battle that he didn’t even have to fight.

Today, people say he was the first man to sail all the way around the world.

But he never returned to Spain. WRITING CHALLENGE

If you were Ferdinand and you were packing for your trip to an unknown destination, what would you pack? Make a comic or write a story about Ferdinand packing for his journey.

Ferdinand Magellan and the First Names series of books are published by David Fickling Books. All illustrations from the book by Tom Knight. Candy Gourlay’s website is here.

You can watch Candy's video Here.

Tuesday, 22 November 2022

Tickling Tastebuds! The Making of a Medieval Banquet by Ally Sherrick

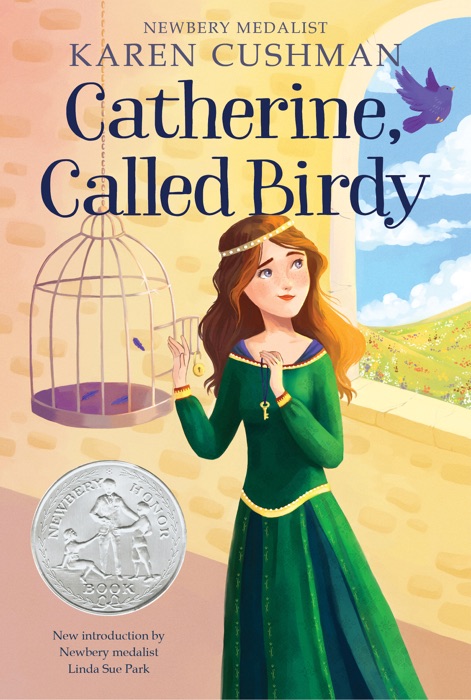

The inspiration for this blog post came from watching the recent film adaptation of Catherine, Called Birdy, American author Karen Cushman’s brilliant coming-of-age novel for young people set in 13th century England.

While I enjoyed the film, the book is even better. Through a series of short, and often laugh-out-loud diary entries, rebellious nobleman’s daughter, fourteen-year-old Catherine, nicknamed ‘Birdy’, recounts her determined efforts to stop her father from marrying her off to a series of unsuitable suitors while at the same time doing her best to resist the attempts of her mother and beloved nurse, Morwenna, to teach her how to be a lady.

Aside from Birdy’s voice and the cast of wonderful characters, from best friend and local goat-herd, Perkin, to the detestable ‘Shaggy Beard’, her future bridegroom, the other thing I love about the book is the brilliant recreation of the medieval world and in particular the banquets and entertainments which Birdy describes.

So, as Christmas is just around the corner, I thought it might be a good opportunity to get those tastebuds tingling by taking a closer look at what went into putting on a feast around the time Birdy’s story is set.

If you are to negotiate your way around a medieval banquet, it’s important to understand that society back then was hierarchical and divided into three broad social classes: the commoners or working classes, the clergy (priests, monks, nuns etc) and the nobility with the King or Queen and their family at the top. Food, like a person’s dress, was an important marker of social status. It was believed that while those working in the fields needed more basic types of food to suit their ‘rougher’ lives and work, the nobility should dine on more refined fare, better suited to their more discriminating digestive systems.

Banquets were a symbol of the nobility’s power as displayed through both their table manners and the meals they ate. But there was much more that went into the staging of a grand feast than the food. For a start, there was the dressing of the hall to be considered. For this, trestle tables would be brought in and covered with tablecloths, while a dresser would be set with drinking vessels, bread boards and serving tools. If guests were expected, then there would also be displays of plate – dishes and other serving vessels made of gold and pewter – all polished to a sparkle to impress.

Everyone attending the banquet had to wash their hands before taking their seats according to their status and position in the household. The lord, lady and their most important guests always sat at the top table, with the youngest, most junior members of the household sitting the furthest from them.

Once seated, everyone said grace. They were then handed trenchers cut from stale bread, or sometimes wood or pewter. These acted as plates into which the food was spooned from sharing bowls and platters handed round by attendants. Before the meal could begin, everyone had to wait for the lord to take a pinch of salt from the ceremonial salt cellar. On the occasion of a grand feast, every dish the lord was served was examined and tasted by a servant to make sure it hadn’t been laced with poison by one of his enemies.

There were no forks at table – these didn’t start to come into use until the very end of the Middle Ages. And diners had to remember to bring their own knives.

For a meal on an ordinary day, the lord might be presented with a choice of six dishes for the first course, though it could be many more at a grand banquet. If you were further down the pecking order, you would choose from just a couple. A second course and the sweetmeats and desserts that followed were offered only to those of the higher ranks.

Ale, perhaps mixed with herbs or else honey and spices, and watered-down wine were served to everyone at table. Though again, only those at the top table could choose how much water to take with their wine.

A stand-out feature of any grand medieval feast table was a ‘subtlety’, a sort of impressive decoration made out of sculpted sugar or else pastry. This was paraded around the hall before being presented to the lord at the top table. The grandest were often several tiers high and might include plaster figures depicting scenes from well-known tales.

Another important feature were the entertainments. Sometimes short plays or ‘interludes’ were performed by players between courses. Or there might be a longer play staged at the end of the meal including performances by musicians, tumblers and a type of costumed actor called a ‘mummer’. A talking point was the inclusion of ‘disguisers’ – people from the lord’s household dressed in masked costumes who might join in the dancing or else act something on their own before disappearing to leave everyone to guess the character they were playing and their true identity.

And now, at last to the food! We’re lucky that some of the old medieval recipes have survived. Here’s a flavour of some of the dishes you might have enjoyed if you had attended a banquet at that time.

Aside from baked goods like bread and rolls, there were vegetable dishes such as braised spring greens seasoned with nutmeg and cinnamon, leeks and onions cooked with saffron, and pottage, a sort of puree made of vegetables such as peas, carrots, leeks, beans and cabbage. Fish dishes included roast salmon in a wine sauce and Pike in Galentine – another type of spice-infused sauce.

Meat dishes might include boiled venison with pepper sauce, spit-roasted pork with spiced wine and, at Christmas, something called a ‘grete pye’ – a pie stuffed with two or three different types of meat (chicken, pigeon or wild duck and saddle of hare or rabbit) plus minced beef mixed with eggs, spices and dried fruit. And for those with a sweet tooth – but only if you were high-ranking remember! – rose-petal pudding, fig and raisin cream, or pine-nut candy.

Anything you couldn’t quite finish would be put in baskets on the tables and taken out after by the lord’s servants to distribute to local workers and beggars at his gates – a feast indeed for those who were used to much humbler ingredients or, worse still, very little at all.

And if you were suffering from an upset stomach caused by too much ‘pye’ the day after, or perhaps a headache from a surfeit of ale, there was usually a Wise Woman or an apothecary on hand with a recipe of their own to set you straight. A bad case of the colic? Then stuff your tummy button with a mixture of rancid butter and chopped saffron covered with a poultice of ale mixed with roasted earth for a sure cure!(?) Though probably best not tried at home!

Happy feasting! Oh, and watch out for those poisoners ...

Watch Ally’s video on medieval banqueting here

Ally Sherrick is the award-winning author of stories full of history, mystery and adventure. Black Powder, her debut novel about a boy caught up in the Gunpowder Plot, won the Historical Association’s Young Quills Award. Other titles include The Buried Crown, a wartime tale with a whiff of Anglo-Saxon myth and magic, and The Queen’s Fool, a story of treachery and treason set at the court of King Henry VIII. Ally's latest book, publishing February 2023, is Vita and the Gladiator, the story of a young girl's fight for justice in the high-stakes world of London's gladiatorial arena. She is published by Chicken House Books and her books are widely available in bookshops and online.

You can find out more about Ally and her books at www.allysherrick.com and follow her on Twitter: @ally_sherrick

Tuesday, 15 November 2022

The First School in the Village by Jeannie Waudby

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE First, watch the Time Tunnellers video about the Viking Attack on the Holy Island of L...

-

VIKING ATTACK! Write a DUAL NARRATIVE ACTION SCENE First, watch the Time Tunnellers video about the Viking Attack on the Holy Island of L...

-

That the Paralympics rose out of such a dark place, from the ashes of the Second World War, wounded men and a fugitive from the Nazis, says ...

-

On Thursday July 4th, the U.K will go to the polls to vote in the General Election. Eligible voters will select from a list of candidates wh...