Have you been to the theatre?

You might have seen a pantomime, or a Shakespeare play, or a big musical with lots of songs and dance routines. Did it make you laugh? Did you cry? Are you excited to see something else? Maybe you’ve even performed in a show and you’d like to be an actor one day.

Theatre is a really popular pastime all over the world and it’s one of my favourite hobbies. In fact, before I became a historian, I spent a very long time working backstage on a show called Les Misérables in London. I was a dresser in a wardrobe department and it was my job to help look after costumes and make sure the actors were wearing the right clothes for each scene. Even though I don’t work there anymore, I do still love to go to the theatre and to experience live performances!

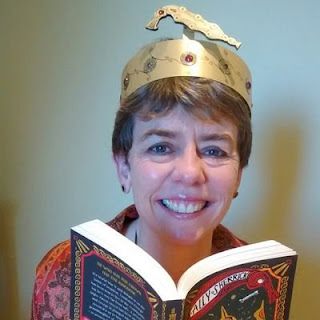

The Histronauts - A Greek Adventure by Frances Durkin

The origins of theatre, as we recognise in the western world, can be traced back to the religious festivals of ancient Greece and the influence of those early performances can still be seen today. When I started writing A Greek Adventure, I knew that I wanted to make theatre a big part of the story. At the beginning of the book, The Histronauts find an old theatre token that transports them back to ancient Greece and they immediately meet a skeuopoios named Kimon who makes all the masks and props that are used in the performances. He tells them all about life in the theatre of ancient Greece and welcomes them to Athens during the Great Dionysia Festival. Festivals to honour the gods took place all over Greece and this annual spring celebration of the god Dionysus featured theatrical performances of brand-new plays. At the end of the festival, the judges chose which plays they liked and the writer of the best play was declared the winner. A very famous playwright named Sophocles won the first prize eighteen times.

Theatres

The theatres of ancient Greece were called amphitheatres. This word comes from the Greek words amphi which means ‘around’, and theatron which means ‘viewing place’. The semi-circular rows of stone seats gave everyone a good view of the performance and the shape of the amphitheatre meant that sound travelled all the way from the stage to the audience members at the very back. The largest amphitheatres that we know about had room for more than 15,000 people. The play itself happened in an area called the orchestra which meant ‘dancing space’. At the back the actors could enter and exit through doors in a skene which was decorated to show the setting for the play. Going to the theatre was a really popular experience for ancient Athenians and audiences would clap, shout, hiss and stamp their feet in response to the play. Many of those amphitheatres are still standing today and they are sometimes used to stage performances for live audiences.

Plays

Three different types of plays were performed at the Great Dionysia Festival: comedy, tragedy and satyr plays. The comedies were funny, the tragedies were sad, and the satyr plays were rude comedy plays. Thousands of plays were written in ancient Greece but today only a handful remain. The oldest one that remains is called The Persians and it was written in 472 B.C. Many of those that we do know are still regularly performed and they give us a wonderful, living insight into what it was like to watch a show in the ancient world. Maybe you might get to see one too.

Actors

Actors brought these plays to life but their performances were quite different from what you would usually see on stage or in a movie today. The earliest known actor was called Thespis of Attica and he lived in the sixth century B.C. You might have heard actors referred to as ‘thespians’ and we get that word from his name. The cast of a play was made up of between one and three professional actors who were paid by the state, and twelve amateur performers, called the chorus, who sang and danced. The actors used painted masks made of leather, wood or cork to show the audience which character they were playing in each scene. The masks all had exaggerated expressions to show the emotions of the characters and wide-open mouths that amplified the actors’ voices. The masks could be quickly changed and this made it easy for the actors to play many different parts in the same play.

Theatre is a wonderful experience that audiences have shared for thousands of years. New and old plays are still being staged all over the world so, next time you see a poster for a show or watch a pantomime, think about the ancient Greeks and how they created something that lives on today.

Writing Prompt

Imagine that you are going to write your own short play for the Dionysia Festival. It can be about anything you like. It could be about a trip to a restaurant, or a day at the zoo, or even a walk in the woods. Will you write a comedy or a tragedy? How many characters do you have? How does it feel to write a story through the dialogue that the actors will perform? What stage directions will you write to describe the scene and their actions? Can you perform your play with your friends?

Frances Durkin

Frances is a writer, historian and author of the award-winning Histronauts book series. She holds a PhD in Medieval History from the University of Birmingham and is most at home wandering around the grounds of medieval castles or sat amongst stacks of books in the library. She is a regular contributor to Aquila magazine and blogs about making history accessible for the entire family, whether that’s through places to visit, books to read, shows to watch, or things to do. You can find out more about her at historiannextdoor.co.uk

The Histronauts books can be bought at all good booksellers or direct from the publisher:

https://bsmall.co.uk/series/the-histronauts