Mobile phones, FaceTime, WhatsApp, social media…

It’s hard to imagine the world without instant communications, but if you ask any

older person, they will tell you that staying in touch has not always been as easy

as it is today.

The Dawn of Modern Communication

Let’s go back 150 years to the middle of the reign of Queen Victoria. The 1800s was a century of change and innovation. Industry, transportation, commerce, and medicine all saw rapid advances, and so did communications. How did people stay in touch in the late 1800s?

A new communication system was Samuel Morse’s telegraph, a system of electrical pulses sent along a wire. The pulses – dots and dashes – formed an alphabet called Morse code. A specially trained telegraphist tapped the message onto the wire and, at the other end of the wire seconds later, another telegraphist transcribed the message. The number of words determined the price of the telegram, so they were often abruptly short. Delivery of the message cost an additional fee. People found telegrams expensive and inconvenient, so they didn’t take off as a common means of staying in touch in the 1800s.

In 1876, Alexander Graham Bell’s freshly

patented telephone entered the communications scene. This new-fangled device

allowed for instant, real-time, person-to-person communication across a

distance, but it took another fifty years for telephones to become common in

homes, changing forever how people communicated.

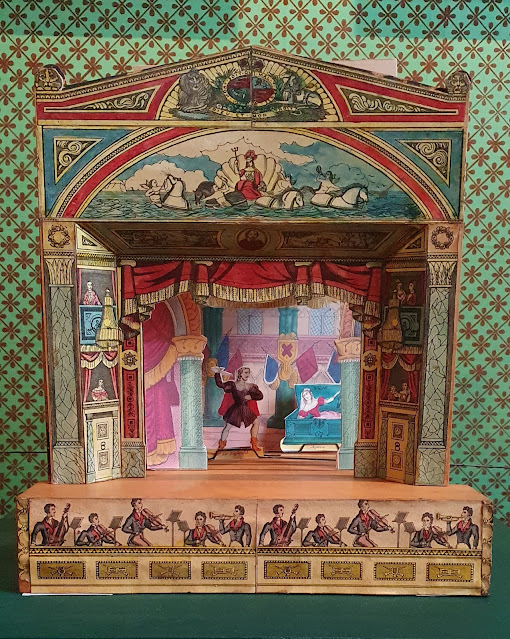

published by Dover Publications, Inc., New York, Public Domain

The Heyday of Handwritten Letters

So how did nineteenth century people stay connected?

They sent handwritten letters through the post. What we call “snail mail” today

was then surprisingly quick – more like “hare mail.” Mid-century reforms enhanced

the British postal system, making it cheap, fast, and very convenient.

Up until the late 1830s, a letter was paid for by the person it was addressed to, and the pricing wasn’t easy to calculate. In 1840, a teacher named Rowland Hill suggested big changes to the postal system: the pricing should be simplified, and the sender of the letter should pay. He invented prepaid, adhesive postal stamps called Penny Blacks, which cost one penny for a letter under half an ounce sent anywhere in the United Kingdom. Pillar boxes were introduced, making letter sending very convenient, and trains shortened delivery time across distances. From 1897, mail was delivered to houses, not just to local post offices.

These reforms started a correspondence craze. By the turn of the twentieth century, the General Post Office handled an estimated 2,740 million pieces of mail – a ginormous increase from the 76 million pieces of mail sent back when Penny Blacks were first introduced.

The mail was delivered between six and twelve times a day in big cities like London. That’s a lot of postie visits! It meant someone could post a letter to someone across town, and they could receive it about two hours a later. There was enough time for them to post a reply, and have it delivered in the same day. It’s not instant messaging, but it’s pretty good!

International mail was a different story back then. For example, letters sent to India or Australia in the early 1800s could take months. Imagine getting important news from home – like a job offer, a birth or a death – late by a few months!

This Victorian love of letter-writing

spawned things like illustrated greeting cards, post cards, and Christmas cards.

Beautiful handwriting was prized, and a lovely, loopy script called Copperplate

was popular. Victorian pens were fitted with metal nibs that were dipped in

bottled ink.

Queen of the Handwritten Word

Queen among the letter writers of the

Victorian Era is Queen Victoria herself. No one knows exactly how many letters

she wrote in her lifetime, but some of her surviving correspondence has been

bound into over sixty volumes (books). Between her mountain of mail and her

daily journaling, it is estimated that she wrote an average of 2,500 words a

day – or approximately 60 million words in her time as queen. That’s a lot of

letter paper and ink!

Queen Victoria is the HM in Her Majesty’s

League of Remarkable Young Ladies, a book set in 1889 London and starring Winifred

Weatherby, a 14-year-old wannabe inventor. The story includes lots of different

forms of correspondence: calling cards, letters, telegrams, Morse code, news

articles, and something called a telautogram.

Smithsonian Institution, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons)

The Telautograph was an extraordinary but forgotten Victorian invention that reproduced and transmitted copies of handwriting and line drawings across telegraph wires. Invented in 1889, Elisha Gray’s Telautograph was an early forerunner of the 1980s fax machine. Read the book to discover if this amazing invention helped or hindered Winifred in her role as gadget maker for Queen Victoria’s league of young lady spies.

Writing Challenge 1: Snail Mail

Snail mail is super fun! The best way to increase your chances of GETTING a letter is SENDING a letter.

Your challenge is to write a real letter to post to someone you know. It’s a good idea to pick someone who is likely to reply. (Hint: Grandparents and older people are usually thrilled to receive a letter and to write back.)

The only rules are:

Write your letter by hand. It doesn’t have

to be long!

Use traditional letter writing conventions:

A traditional salutation: Dear _____, / My

dearest ____, / etc.

A message (Ideas: something about you,

questions about them, something you’re proud of, etc.)

A traditional closing: Yours truly, / Your

loving (grandchild), / Warm regards, / etc.

Your signature: Can you do a Copperplate

style signature with lots of lovely loops? Have a go!

Address the envelope and affix a stamp. You

might have to ask for help if you don’t know the address. And you might need to

ask for a stamp from your parent or carer. Don’t forget to write your return

address on the envelope!

Post it in a Royal Mail pillar box and smile because your letter will brighten someone’s day!

Challenge Two 2: Code Cracking

Can you decode this Morse code message?

.. - / .. ... / ..-. ..- -. / - --- / .--

.-. .. - . / .-.. . - - . .-. ...

I T / I

S /

[It is fun to write letters]

Try writing your name in Morse code.

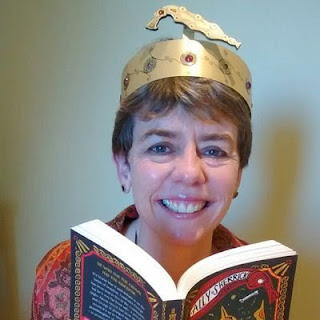

Alison D. Stegert has worked as an innovative school counsellor, a bumbling waitress, and an intrepid English (EFL) teacher, but writing kids’ books is her dream-come-true job.

Her latest book, Her Majesty’s League of Remarkable Young Ladies, was published in the UK in July 2023 and released in Australia by Scholastic in 2024. The book is the result of Alison’s 2021 win of the international competition The Times | Chicken House | IET 150 Prize.

Aussimerican Alison is a long-term resident of Queensland, where she serves as state director of the Queensland branch of SCBWI Australia East and the chief scribe at the Sunny Coast Writers’ Roundtable.