April is Care Experienced History Month so I wanted to feature the Foundling Museum in London.

Foundling Museum

Although it isn’t the original building, it's built on the site of the original Hospital.

Engraving of the original Foundling Hospital in the 1750s

The story begins in the mid 18th century when a retired sea captain and shipbuilder, Thomas Coram, returned from America with his wife Eunice. He was shocked by the poverty he saw, and the dead and dying babies in London’s streets. It was a time of extreme prejudice against unmarried mothers and their babies. He lost his own mother when he was only 3, and was sent to sea at the age of 11, and maybe these early separations gave him the insight to care for other children who had been separated from their families.

Captain Thomas Coram by William Hogarth, 1740

He decided to try and do something. It wasn’t easy because of the stigma but after 17 years he found support from ‘21 ladies of distinction’ and in 1739 received a charter from George II to build the hospital. In doing this, he started the UK’s first children’s charity.

As soon as it opened, the Foundling Hospital was inundated with babies. Mothers would bring their baby, often leaving a token to identify them as the child’s mother in the hope that they could reunite in the future. Some of these tokens are on view at the Foundling Museum, and they are heart breaking to look at.

Some of the tokens in the Foundling Museum

Some of them are simple objects that have been altered to make them more distinctive.

A bent thimble

Others are valuable or even engraved and show that not all the babies were there because of poverty.

An engraved token for Stephen Large

Some are handmade with a huge amount of care.

A lovingly crafted heart-shaped token

Life changed completely for the babies who were taken into the Hospital. They were given new names and sent to foster mothers in the countryside for the first four or five years, and many of them got to experience family life and love. But then they had to return to the Hospital, living communally and wearing a uniform.

It must have felt like losing their mum all over

again. Many of the foster mothers wanted to keep the children they had looked

after, but this didn’t often happen. Life would have become very different, in

an institutional environment with boys and girls segregated. But the children

received good healthcare and food and an education.

They were taught to read

and there was a choir so they also had music in their lives. At 13 or 14, later

16, they would be apprenticed or sent into service – having received an

education that prepared them for hard work.

Girls in the Chapel by Sophia Anderson, 1877

Children with their foster mother in 1900

In the early days, the Foundling Hospital had a lottery for which babies would be accepted – mothers had to pick a white ball out of a bag to get their baby in. In 1756 because of the demand, they made admission open and babies could be left in a basket and a bell rung to alert staff. But this caused the mortality rate to go up from 45% to 81%. It also meant that middlemen could charge mothers money to take their baby to the Foundling Hospital, with many dying on the way.

London's Forgotten Children by Gillian Pugh and Coram Boy by Jamila Gavin

Jamila Gavin’s fascinating teen novel CORAM BOY deals with this situation, as well as painting a vivid picture of 18th century England and capturing the vulnerability of children in a time of poverty and slavery. LONDON’S FORGOTTEN CHILDREN by Gillian Pugh tells the story of Thomas Coram and is packed with photos tracing the Foundling Museum’s history. In 1801 they changed the rules – babies had to be illegitimate and mothers had to bring their baby themselves.

All the babies were baptised and given a new name. In spite of the tokens and later receipts mothers were given when they left their baby, not many children were able to return to their mothers.

The Foundling Restored to its Mother by Emma Brownlow, 1858

This painting from 1858 by Elizabeth Brownlow, a self-taught artist, shows a mother coming back to reclaim her little girl. The man behind the desk is the painter’s father John Brownlow. He was himself raised in the Foundling Hospital and later worked his way up to become its governor. It's possible that the kind Mr Brownlow in Dicken’s OLIVER TWIST is based on him. The certificate proving that the mother and child belong together has fallen on the floor.

The hospital moved first to Redhill and then to Berkhamsted where the air was fresher, where it remained until 1955. In the Foundling Museum, you can listen to recordings of people talking about their experience of growing up there in the 20th century.

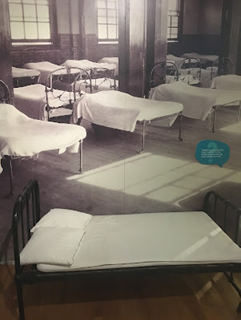

A photo of a dormitory and one of the beds in the museum

In the 1960s, people came to understand that an institutional childhood, whether it is in a children’s home or a boarding school, makes it very difficult to meet a child’s emotional needs and that most children thrive in a family instead.

Coram has evolved into a charity committed to improving the lives of the UK’s most vulnerable children and young people. You can find its website here

It is currently working on Voices Through Time: The Story of Care , which aims to digitise the records of Coram’s work so that the voices and stories of children looked after through the Foundling Hospital can be saved for generations. It will include registers, documents about the children, letters from mothers and the records of fabric tokens mothers left to connect them to their child. Coram hopes to have this archive online in 2023.

Coram Foundling Hospital in 1746/50 by Richard Wilson

Writing challenge

We’ve seen some of the tokens mothers left with their babies, to represent their love and in the hope of connecting again one day. Centuries later, we can look at these heartbreaking little objects and in doing so, keep their memory and story alive.

For this week’s writing prompt, think of an object that you could give to someone as a keepsake, to remind them of you. It can be simple or precious, imaginary or real, manufactured or natural, but small enough to fit in the palm of your hand. Describe this object – its colour, shape, what it’s made of, where you got it or how you made it. What does it say about you? What makes it special?

Jeannie Waudby is the author of YA thriller/love story One of Us (Chicken House.) She is currently writing a YA novel set in Victorian times.