In 1945

the people of Lakeland welcomed three hundred child Holocaust Survivors into

their community.

Lake Windermere

(photo Susan Brownrigg)

A special exhibition at Windermere Library From Auschwitz to Ambleside highlights what life was like for these children. I visited to find out more.

Windermere Library, home to the

Auschwitz to Ambleside exhibition

(photo Susan Brownrigg)

In 1942

the Nazis began what they called ‘the Final Solution’ - a plan to exterminate

all Jewish people across Europe. Roma gypsies, gay and disabled people, as well

as black and mixed-race people were also persecuted and killed.

It's estimated that eleven million people died in the

Holocaust including six million Jewish people

By the

end of World War II, approximately 90 per cent of Europe’s Jewish children were

murdered in the Holocaust.

In June 1945, Leonard Montefiore, of the Central British Fund

(now World Jewish Relief), persuaded the British Government to give permission

for a thousand Jewish orphans aged from eight to sixteen to be brought to the

UK for recuperation, and ultimate re-emigration overseas.

Just 732 actually came to Britain. They became known as The Boys, though they included 204 girls.

Of these, 300 children who had survived the Theresienstadt Ghetto

in the Czech Republic were brought to Windermere. The youngest were just three years old.

Many of the children no longer knew how old they were and could not remember their date of birth, and lots were older than sixteen.

The

Lake District Holocaust Project which curated the exhibition explains: “The Jewish children who came to the Lake District had been

liberated in May 1945. Many had been used as slave labour in many camps

across Nazi Occupied Europe for a number of years. The list of names of the

camps they had experienced is an A-Z of horror. Auschwitz, Buchenwald,

Majdanek, Warsaw ghetto, Lodz ghetto…..they each had a different story to tell

of a different journey. Their discovery in Theresienstadt does not begin to

cover their story.”

The children were to spend a period of recuperation in the Lakes before setting out on new lives.

The children were flown from Prague to Crosby on Eden airfield near Carlisle.

The Immigration Officer said: “The behaviour of the children was exceptionally good.”

From there the children were taken in a convoy of buses and army trucks to Calgarth - a wartime housing estate built to accommodate workers from the Short Sunderland Flying Boats factory on the shores of Windermere.

The single workers no longer needed the rooms at the now lost estate, near Troutbeck Bridge - and there was the perfect number available for each child to have their own private room.

Arriving in the Lake District was described by the children as like being in “Paradise”.

The Lake District Holocaust Project website explains: “The estate had its own shops, canteen, entertainment

hall and many other facilities. They were each given their own small

room, a bed and clean linen. For many it was their first encounter with privacy

and cleanliness in five years.”

One quote on display is from Ben Helfgott, who was 15 when he came to Calgarth. “I'll never forget the smell of the fresh linen I slept on that first night ... I can't remember ever having a better night sleep ... It was only a hut, but to me it was a palace.”

The children who came to Windermere

were given a copy of Pears' Cyclopaedia

The children became known as the Windermere Boys - although the group included 35 girls.

Most young survivors were male and the Nazis considered girls less useful for slave labour.

When they arrived they could not speak English, so they were given language lessons.

The children were offered opportunities for sport, education,

outdoor recreation and healthcare.

Over a period of six months, they were

gradually moved to other homes in places throughout the UK, and they had left

Calgarth Estate by early 1946.

Around 30-40 children moved to Manchester, others to Liverpool, Gateshead and London. Some left Britain, to America, Canada and Israel.

Outside the library there is a memorial garden to the Windermere Children with colourful artwork and planting that tells the journey of the children through the language of flowers.

The interpretation explains: “Many of the children spoke of their love of the luscious green of the Lake District and described it as an explosion of colour after the horrors of the camps.”

Plants chosen include heather (protection) daffodils (new beginnings) and snowdrops (hope.)

From Auschwitz to Ambleside exhibition, Windermere Library

(photo Susan Brownrigg)

The children's story is also retold in the BBC

film The Windermere Children and the accompanying documentary The Windermere Children: in their own words.

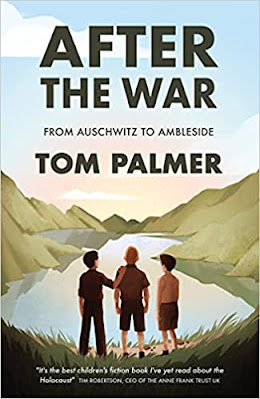

After the War from Auschwitz to Ambleside by Tom Palmer

The

book After the War : From Auschwitz to Ambleside by Tom Palmer tells the story of the Windermere Boys in a dyslexia friendly accessible format. It is published by Barrington Stoke. The Centre for Holocaust education offers lesson plans

for schools studying the book.

The '45 Aid Society was set up in 1963 by some of the 732 children who came to Britain in 1945. Their children continue the society's work.

Holocaust Memorial Day Trust (HMDT)

encourages remembrance in a world scarred by genocide. They promote and support

Holocaust Memorial Day (HMD) – the international day on 27 January to remember

the six million Jews murdered during the Holocaust, and the millions of people

killed under Nazi Persecution and in genocides in Cambodia, Rwanda, Bosnia and

Darfur. 27 January marks the anniversary of the liberation of

Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest Nazi death camp.

Useful links:

https://www.hmd.org.uk/take-part-in-holocaust-memorial-day/schools/primary-schools/

https://holocausteducation.org.uk/lessons/open-access/lesson-materials-to-support-after-the-war-a/

https://www.worldjewishrelief.org/about-us/the-boys

https://45aid.org/